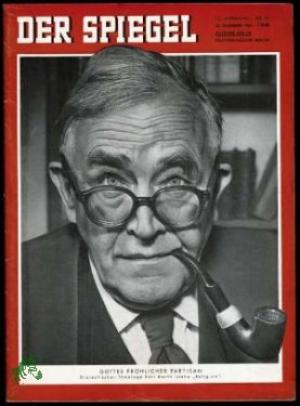

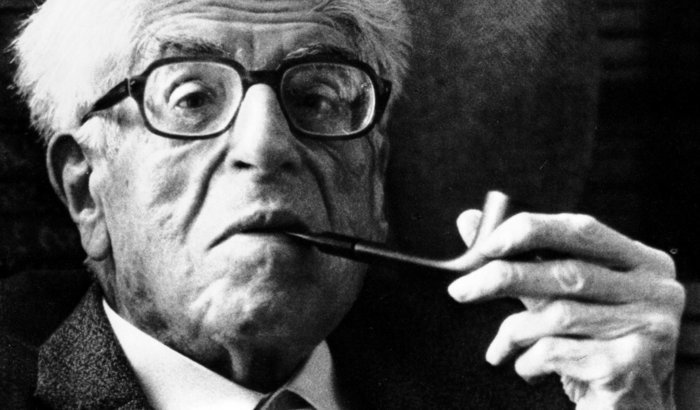

On May 2nd, 1933, Rudolf Bultmann began his lecture series unusually, with a comment about the rapidly developing German political situation.

On May 2nd, 1933, Rudolf Bultmann began his lecture series unusually, with a comment about the rapidly developing German political situation.

Ladies and gentlemen! I have made a point never to speak about current politics in my lectures, and I think I also shall not do so in the future. However, it would seem to me unnatural were I to ignore today the political situation in which we begin this new semester (in Existence & Faith: Shorter Writings of Rudolf Bultmann, 158).

He is quick to note that what he aims to say is not political per se, but to inquire ‘what our responsibility is as theologians in face of these possibilities’ (158).

Bultmann begins by describing the relation of faith and politics as an implication of faith in God as Creator and Judge of the world, and its Redeemer in Jesus Christ. Faith in God as Creator is not a philosophical theory or the foundation of one’s worldview so much as the confrontation in which God encounters us as Lord in the concrete experience and situation of our everyday existence. This faith is realised in our experience and action in the moment, not as a general response of, say, ‘cultivating our humanity,’ but in our obedience to our Lord as this man or this woman in this place, time, and situation. Bultmann’s understanding of the situation includes our existence within the scope of the ‘ordinances of creation’ which includes such things as family, work and possessions, the relations of the sexes and those of different age, education, nationality, and state. Faith in God, then, stands in a positive relation with nationality since God has placed us in our nation and state, and encounters us in and through these earthly realities (159).

It suffices to understand—in the words of F.K. Schumann—that ‘nationality means being subject to an original claim; that to stand in a nation or to be a member of a nation means to share a common destiny, to subject oneself to the claim of the past, to let one’s own existence be determined by others, to be responsible for a common future, to receive oneself from others and thus also to be able to sacrifice oneself in return’ (159-160).

Although God encounters us in and through creaturely realities, he is not immanent within them, nor to be identified with them: he is the Creator and as such stands outside and beyond the creation. That is, God is not merely Creator but also Judge, and thus our relation to the ordinances is not merely positive but also critical. Bultmann cites 1 Corinthians 7:29-31 to argue that human sinfulness corrupts our relation to the ordinances of creation, making the creature self-serving:

Everything . . . can become sin at man’s hands; i.e., it can become a means for pursuing his own interests and disposing of his existence. Therefore, all of the ordinances in which we find ourselves are ambiguous. They are God’s ordinances, but only insofar as they call us to service in our concrete tasks. In their mere givenness, they are ordinances of sin (160).

The ordinances may be placed at the service of God or of sin, though their original purpose was the service of God who by them intended to bind us one to another in relations of justice. But we and all our history are also ambiguous, shaped inevitably by our history of sin, infected with a “sinful self-understanding in which man wills to pursue his own interests and to dispose of his existence” (162).

With these thoughts now in mind, Bultmann turns again to the question of nationalism:

No state and no nation is so unambiguous an entity, is so free from sin, that the will of God can be read off unambiguously from its bare existence. No nation is so pure and clean that one may explain every stirring of the national will as a direct demand of God. As nature and all our personal relations with one another have become uncanny as a result of sin, so also has nationality. From it emerge deeds of beauty and nobility; but there also breaks out of it the demonry of sin (162).

Thus, it is the role of Christian faith, “precisely in this time of crisis,” to ask again, “what is the true and normative meaning of the nation” (162). It demonstrates its “essentially positive character precisely in its critical stance” (162). The criticism offered by the church is grounded not merely in its knowledge of sin but also of grace. It knows God not merely as Creator and Judge, but also as Redeemer. This knowledge provides the believer with a criterion by which to measure the noisy demands of the day, “by asking whether and to what extent they serve the command of love” (163). In the “present struggle” this criterion must be applied concretely rather than as an abstraction, and be applied to oneself as well as to others. That is, we must be concerned with “the concrete neighbor to whom we are now bound in the present by all the commonplace ties of life” (163). Further, only those may truly serve the nation who view each neighbour in light of this criterion; that is, those who have been freed to love by receiving the love of God in Christ.

Bultmann concludes his address with a powerful and straight-forward exhortation to act responsibly in light of the critical power of this Christian faith.

Will we preserve the power of our critical perspective and not succumb to the temptations, so that we may work together for Germany’s future with clean hands and believe in this future honorably? Must I point out that in this critical hour the demonry of sin also lies in wait? (164)

The slogan—We want to abolish lies!—from a recent student demonstration provides a means for making his call concrete. He deplores the widespread use of denunciation and defamation to label and castigate opponents as an example of ‘lies’ used, supposedly, in their abolition.

‘We want to abolish lies!’—and so I must say in all honesty that the defamation of the Jews that took place in the very demonstration that gave rise to this beautiful sentiment was not sustained by the spirit of love. Keep the struggle for the German nation pure, and take care that noble intentions to serve truth and country are not marred by demonic distortions!

But there is yet this final word. If we have correctly understood the meaning and the demand of the Christian faith, then it is quite clear that, in face of the voices of the present, this Christian faith itself is being called in question. In other words, it is clear that we have to decide whether Christian faith is to be valid for us or not. . . . And we should as scrupulously guard ourselves against falsifications of the faith by national religiosity as against a falsification of national piety by Christian trimmings. The issue is either/or!

Read 1 Samuel 1

Read 1 Samuel 1