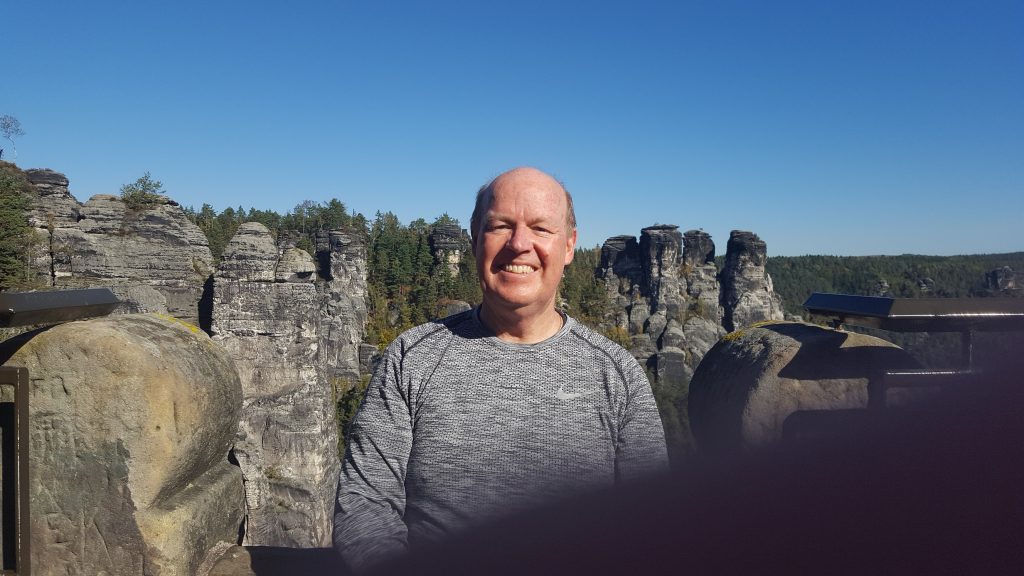

This time last year I spent five weeks in Germany, four in Dresden taking a language course at the Goethe Institut. On the weekends we tried to get out a little to see something of the country. This weekend we went to the sächsische Schweiz – the Saxon Switzerland, a national park on the Elbe River, about 30 kilometres from Dresden and close to the Czech border. I am sitting next to Maylis from Geneva who was not in our class, but in a higher class. Geneva is in the French-speaking section of Switzerland and Maylis was improving her German to improve her employment opportunities.

This time last year I spent five weeks in Germany, four in Dresden taking a language course at the Goethe Institut. On the weekends we tried to get out a little to see something of the country. This weekend we went to the sächsische Schweiz – the Saxon Switzerland, a national park on the Elbe River, about 30 kilometres from Dresden and close to the Czech border. I am sitting next to Maylis from Geneva who was not in our class, but in a higher class. Geneva is in the French-speaking section of Switzerland and Maylis was improving her German to improve her employment opportunities.

Next to Maylis is Tony from Saskatchewan in Canada. Tony was in my class, learning German as a hobby and perhaps reclaiming his roots since he has German forebears. Next to Tony was Donald, a very typical older New Yorker, bold, self-sufficient, a little crusty, and really quite remarkable, flying to another country to learn a new language at 82 years of age. He was in a beginner’s class, and so not in our class. Maybe I can still be travelling and learning at that age!

The next two women were also in my class. Anna, from Japan, was born in Germany because her parents lived and worked there when they were young. Now she has left her homeland to do the same. She was at the Institut for three months and then planned to move to München to find work. And next to Anna is Maria, originally from Spain but now working in a German-speaking area of Switzerland.

A couple of days after this Tony and Maria ended their course while Anna and I stayed on. Others in the class also left and it shrank from seven or eight members to three (there was another young man from Columbia, a cheeky fun-loving gay dude who had moved to Germany for work and the experience). I was left as the old bloke in the class…

This was a much better day than the previous weekend when we visited the historic town of Meissen, a pretty town a little down the Elbe from Dresden. That had been a miserable day, cold, rainy, pure east German autumn!

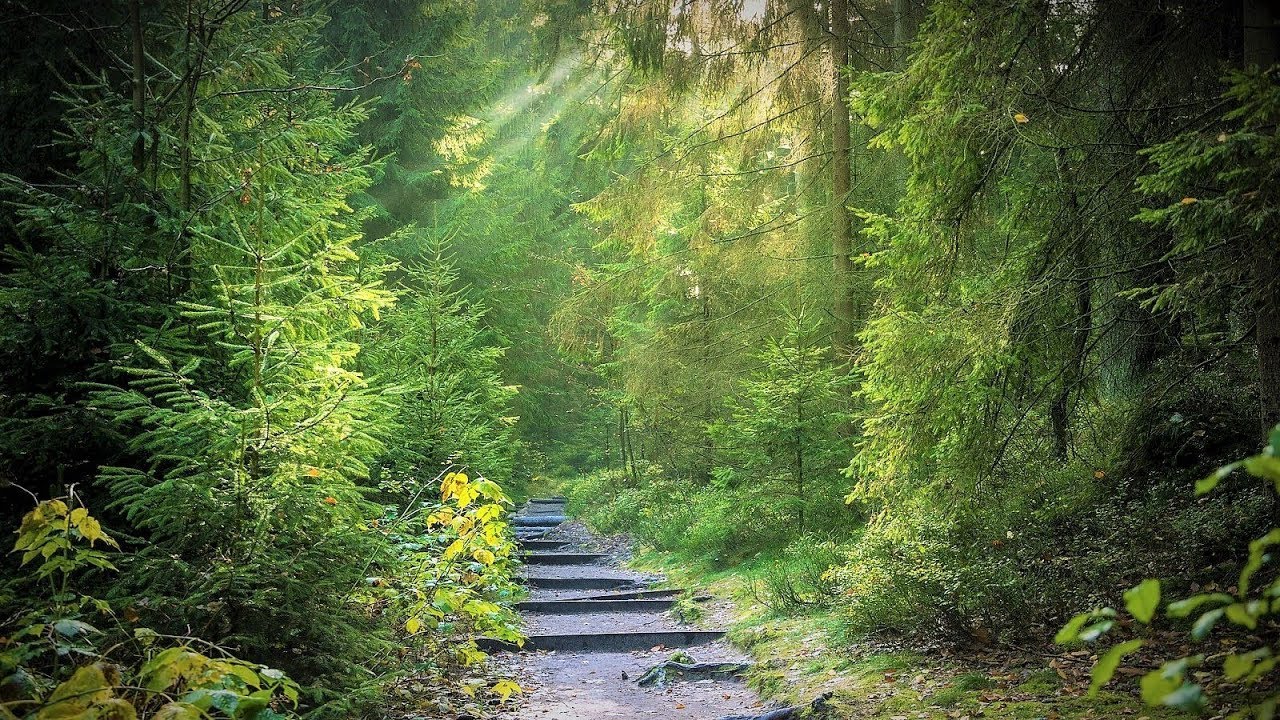

We had a beautiful Autumn day for hiking in the rather spectacular hills here. The first photo is from one of the lookouts, looking up the Elbe toward the Czech border. The second is the bridge and view in the unusual hill formations that make this region famous.

It is really worth a visit if you are ever in central Europe. I would like to go again!