The last week has been somewhat different for me: I have been home on sick-leave.

The last week has been somewhat different for me: I have been home on sick-leave.

Last Monday I had surgery to remove a small skin cancer on my left lower eyelid. The surgery itself, although occurring under the hand of two different surgeons in two different locations, was relatively simple and surprisingly pain free. For that I am grateful. The worst I have experienced is an itchiness under the dressings: an annoyance, but nothing substantial.

I have had skin cancers removed on previous occasions, and usually, it is not a big deal. The difference this time was its location: being on the eyelid made its removal somewhat tricky. Not the removal exactly: that was quite straight-forward, although, in accordance with the particular procedure I was having it involved two excisions and two periods of waiting for pathology results. But because the extent of the growth was unknown prior to its excision, I did not know how much repair or reconstruction of my eyelid would be required. Worst case scenarios involved skin grafts from another part of my body, as well as cutting a “flap” from my upper eyelid and folding it down and stitching it onto the remains of my lower eyelid, thus effectively stitching my left eye shut for a month or so.

I am quite fussy about my eyes, and quite protective of them. I do not use contact lenses because I am queasy with the thought of poking around in my eyes. I am very careful these days if I am using a drill or an angle-grinder or something similar. You might say I am a bit of a wuss. So the thought of the surgeon dicing and slicing, pricking and prodding all around my eyes—I would be awake and fully conscious for the entirety of the excisions—was quite anxiety-inducing. Not serious, debilitating anxiety, but a back-of-the-mind nervousness and apprehension.

Fortunately it all went smoothly. I ended up with a quite minor repair to the eyelid apparently; I will see for myself when the dressings come off in another two days. Yes there will be bruising and scarring, but all in all, I am very fortunate. The options, you see, were not at all good. Even though the kind of skin cancer I had (a basal cell carcinoma) is the kind to have if you must have one, they still grow.

How long would it have been until I had an unsightly lump on my face causing my eyelid to droop, and the function of my eye to be impaired? Might the cancer had spread its roots into the eye itself? These possibilities would have caused me serious, debilitating kinds of anxiety, I think.

But I live in Australia, and I have health insurance. These two facts give me timely access to some of the best medical practitioners, treatment and care in the world.

The whole experience has been good not just for my body, but for my soul. I am blessed, and now also more aware of this blessedness in contrast to many others around the world who may have the same condition but without the same access to treatment and care. And along with the sense of blessing is an increased awareness of the responsibility which is also mine, to share this blessedness with others in practical ways.

I have renewed appreciation for the gifts, skill and dedication of so many others who have made this treatment possible: from the surgeons and other medical professionals, to the tax-payers and governments who plan and fund hospitals, to the architects and builders, and so on. God has given such a vast array of gifts and many have used them for the common good. I have been the recipient of this grace through the involvement of others.

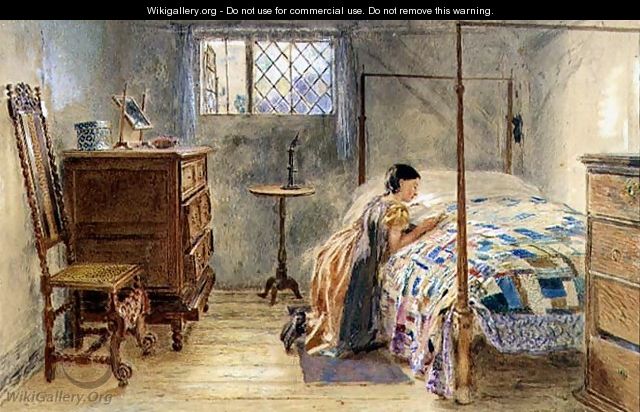

And my week at home has been good for the soul. I haven’t been very prayerful, I must confess. But I have been mindful of God’s goodness and presence. I have had the use of only one eye and so am reminded of the blessing of two. The remaining eye did not function very well for the first few days after the surgery, and it is difficult to focus with my glasses perched on the tip of my nose! I am self-conscious about my appearance with a large dressing covering half my face. But I have also realised that it is not that big a deal.

I have slept more, rested more, browsed the newspaper, watched some TV, gone on long walks; it has almost been a holiday. And that too, has been good for the soul, and a timely reminder not to lose my life to my work no matter how much I enjoy my work. The enforced rest has been good for me body and soul. I must do it more often, and voluntarily.