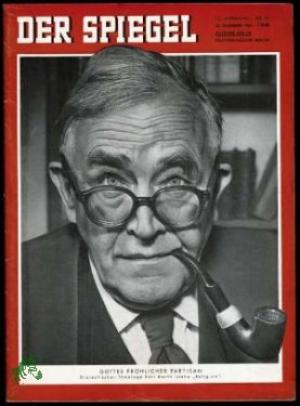

Last week I posted on Barth’s “conversation” at the Zofingia Student Association meeting on June 3, 1959. At this meeting Barth addressed the questions put to him, What are the role and duties of the Christian as a political citizen? Does Christianity commit the citizen to a certain political stance? He responded with 10 theses as follows:

Last week I posted on Barth’s “conversation” at the Zofingia Student Association meeting on June 3, 1959. At this meeting Barth addressed the questions put to him, What are the role and duties of the Christian as a political citizen? Does Christianity commit the citizen to a certain political stance? He responded with 10 theses as follows:

- The Christian is witness to the kingdom of God (= basileia) that has come in Jesus Christ and is still to be revealed in him.

- As a witness of the kingdom of God, the Christian is first and foremost a citizen of this kingdom.

- The Christian lives in each particular time and situation also as a citizen of a state in one of its different and changing forms.

- The Christian acknowledges the kingdom of God in the provisional order of God for the establishment and preservation of relative justice, relative freedom, and relative peace in his state.

- The Christian does not mistake the state, in any of its many forms, for the kingdom of God.

- The Christian does not fear or deny the state in any of its many forms, because each state contains something divine.

- In view of the kingdom of God, the Christian distinguishes between forms of the state insofar as they more or less correspond to the divine appointment.

- The Christian, as a citizen of the state, bears witness to the kingdom of God, insofar as he decides in each case for the more appropriate form of the state, meaning the more righteous form.

- The Christian decides about the preferable form of the state as well as about the form of his support for it, with a new, free orientation toward the kingdom of God in each particular time and situation.

- The Christian is always obligated to assume the particular political stance and action that correspond to his reflection on the kingdom of God (“Conversation in the Zofingia 1 (1959)” in Busch ed. Barth in Conversation Vol. 1, 1959-1962, 2-5).

The first three theses are uncontroversial. The wording of the fourth is a little obscure, but is simply declaring that the state is a divinely ordained institution for the establishment of (a relative) justice, freedom, and peace in human society. This, too, is uncontroversial as is thesis five. The sixth thesis is controversial, especially Barth’s assertion that every form of the state contains “something divine.” One immediately thinks of his own repudiation of Nazism in the 1930s. In his comment on this thesis Barth argued:

Ancient Christianity existed even in Nero’s empire. There is no anti-Christian state, and there is no civitas diaboli. The Christian is therefore protected against political scepticism or political despair. A Christian will affirm the state in each form. He distinguishes [certainly between better and worse forms of the state, but he does so] while never pronouncing an absolute yes or no. Therefore [since “each state contains something divine,”] he [the Christian] is not forced [or justified] to take a stance of neutrality [toward the state]. [Rather] he distinguishes between states of lesser or greater justice (4).

It may be that the “something divine” is nothing more than its institution as a state. It seems, though, that despite Barth obviously making a comment about the nature of every state—and about divine sovereignty, his intent is to describe the Christian’s posture toward the state; there is no room for scepticism, despair, or neutrality. A state cannot be proclaimed absolutely evil or just, but must be distinguished according to its relative degree of justice, and according to thesis seven, the canon for this assessment is the kingdom of God.

Theses eight and nine form a pair, with the Christian deciding in each case for the more appropriate form of the state and the nature of their support for that more appropriate form. They are not bound to traditions, conventions, concepts of natural law, or other approaches of response to the state. They may, of course, resort to such ways of response, but are free in each situation to evaluate the state in the light of the kingdom of God, and respond appropriately. Nor is the Christian required by God, theology, the church, or Scripture to support only this kind of state, or that. Nor is the Christian’s posture toward the state always critical: “it is possible for him to work actively within a dictatorship: for example, by enduring, by waiting in the quiet hope that the trees will not grow sky-high, or even by cooperating (more or less)” (4). This liberty—Barth’s refusal to prescribe a Christian posture or mode of action—is also the theme of the final thesis. The Christian must always take a stance; the Christian must always act, but they are free to do so in accordance with their own reflection on the kingdom of God. In this, “the Christian has . . . no choice, but rather only one possibility: the stance that he has been commanded to take” (5).

It is clear that in the final theses Barth applies his theology of the divine command to the Christian as citizen. Also clear, is that he is thinking as much about the believers in the communist east as he was in the democratic west. His answer to the two key questions asked: What are the role and duties of the Christian as a political citizen? Does Christianity commit the citizen to a certain political stance? are that (a) the Christian is to witness to the kingdom of God within each particular form of the state, including the support of justice, freedom, and peace in human society as an analogue of that kingdom; and (b) no, the Christian is not committed to a pre-determined political stance, but are always to act in accordance with their (no doubt theologically-informed) understanding of the kingdom of God.