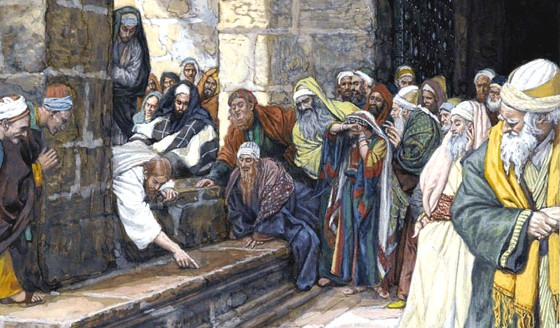

Samuel disappears in chapters five and six, as do all the major characters in the story thus far. The scene shifts from Shiloh to Ashdod, and the main character in the story is now the Ark itself, which has been captured by the Philistines and installed in the temple of Dagon at Ashdod. The defeat of an enemy in the ancient world also signified the defeat of that enemy’s god. This is exemplified in the capture of the Ark; not only is Israel defeated, but their god has been captured. Bringing the Ark into the temple of Dagon is an act of celebration of Dagon’s triumph and supremacy over the god of Israel. The Ark becomes a trophy and symbol of Dagon’s power. Israel’s god was unable to defend its own people from the greater power of their opponents and their god.

In the Hebrew Bible Dagon is associated with the Philistines who perhaps adopted Dagan as their national deity soon after they arrived in Palestine early in the Iron Age (Tsumura, “Canaan, Canaanites” in DOTHB, 127). Dagan was a traditional god of Syria-Palestine, attested as early as the third millennium BCE. Although identified as a fish-god since the medieval period, more recent scholarship suggests his name has more to do with grain, and thus was perhaps a fertility deity associated with agriculture. He was in any case understood as a powerful god. Excavations at Ugarit have unearthed two temples in the city, one devoted to Baal, the other to Dagan. In the Ugarit pantheon, consisting of as many as 240 deities, Dagan was second to El and understood as father to Baal (see Curtis, “Canaanite Gods and Religions” DOTHB, 132-142). Philistine attachment to and trust in Dagon is seen in Judges 16:23-24 where the Philistines credit Dagon with their victory over Samson—although the story did not end well for the Philistines in that instance.

The commentators suggest that this passage is to be understood as humour (for Israelite readers at least)—black humour to be sure—the function of which is to mock the Philistines and their god. The opening scene pours scorn on the supposed power of Dagon, for the idol falls not once but twice before the Ark. After the first fall, Dagon must be helped back to his plinth; after the second, he is broken in pieces, his impotence plain for all to see. The story functions apologetically, to repudiate a possible interpretation concerning the capture of the Ark. Israel’s God has not been defeated by a greater power. Indeed the story demonstrates the livingness of Israel’s God compared to the lifelessness and impotence of Dagon. In the “Battle of the Gods” Dagon’s claims are slapped down and exposed as pretensions. The story also then, shows that the defeat of Israel, far from being the defeat of Yahweh, was the judgement of Yahweh upon his people as predicted by the anonymous man of God in chapter two. Further, it clearly indicates that Yahweh as the living God cannot be manipulated by his people, but retains his sovereign freedom.

Nor can the Philistines subject Israel’s God to their own will. Not only is Dagon assaulted, but the people of the Philistine cities also experience an outbreak of plague that seems coordinated to the presence of the Ark among them. The text itself is clear: “the hand of the Lord was heavy against the people of Ashdod, and he terrified and afflicted them with tumours” (verse 6), with the result that many died (verse 12). Modern scholars wonder if the plague may have been a form of bubonic plague spread by a plague of mice (6:4-5).

Murphy, utilising the LXX’s rendition of 5:9, refers to the tumours as genital warts, or more colloquially, “bum-warts” (44). She uses this story to reflect on the character of miracles and divine power in conversation with John Henry Newman who suggests that the portrayal of the Ark-miracles in this chapter might be analogous to the somewhat wild and “romantic” nature of post-biblical miracles. Typically, those who defend the miracle accounts in scripture argue for the rationality of these miracles because they fit with what may be known of God from nature and morality. But not all biblical miracles fit that mould. Murphy finds little in this chapter’s account of miracles that conforms to reason, morality or beauty. But they are not on that account to be rejected. They are “divine punishments” that teach us that “the hand of God can appear at will and in the unlikeliest “Elishas” because it is not subject but sovereign” (46). The account challenges our perceptions of God, especially a god we would manipulate, contain, or set in a box. Murphy cites John Henry Newman to warn against such limitations on God, or interpretive strategies which make the biblical portrayal of God more amenable to our sensibilities. If I read her rightly, she wants to leave open the possibility that God will not conform to our demands of what we think God should be. In this respect God is sovereign, and as such, sovereignly free.

The supernatural glory might abide, and yet be manifold, variable, uncertain, inscrutable, uncontrollable, like the natural atmosphere; dispensing gleams, shadows, traces of Almighty Power, but giving no such clear and perfect vision of it as one might gaze upon and record distinctly in its details for controversial purposes. Thus we are told, “the wind bloweth where it listeth” (cited in Murphy, 46).