Drink water from your own cistern and fresh water from your own well. Should your springs be dispersed abroad, streams of water in the streets? Let them be yours alone and not for strangers with you. Let your fountain be blessed, and rejoice in the wife of your youth. As a loving hind and a graceful doe, let her breasts satisfy you at all times; be exhilarated always with her love. For why should you, my son, be exhilarated with an adulteress and embrace the bosom of a foreigner? For the ways of a man are before the eyes of the Lord and he watches all his paths. His own iniquities will capture the wicked, and he will be held with the cords of his sin. He will die for lack of instruction, and in the greatness of his folly he will go astray.

I had not been a Christian very long, before I stumbled across this passage in Proverbs. Still unmarried, a young man, all it took was the word “breasts,” and my attention was captured! Over thirty years have passed since then, and I am still pretty much the same.

This passage is both a celebration and warning, though the note of warning captures the function of the chapter as a whole. As is often the case in the early chapters of Proverbs, the passage is addressed to “my son,” and may be conceived as parental instruction (cf. Proverbs 1:8; 4:1-3; 6:20). In many cases the instruction might just as easily be addressed to “my daughter.” Though that might go against the cultural grain of the text in the period when it was written, it is certainly appropriate today to recognise the equal value and blessing of both daughters and sons, and to affirm their equivalent need for instruction. Having affirmed that, however, it may also be noted that the particular theme of this chapter is appropriately addressed to “sons” (5:7). The recent Ashley Madison hacking scandal indicates once again, the relative disparity between men and women with respect to sexual promiscuity. Although the owners of the website claimed the client gender split was 60% male – 40% female, the hackers claimed the true figure was probably higher than 90% male.

The first fourteen verses warn the son against the “adulteress” (v. 3), who lies in wait for his life (cf. 6:26; 7:23). In the early centuries of the church, it is clear that women were often and unfairly seen as the source of sexual temptation, as sexually dangerous, and perhaps even as predatory and inherently immoral. If we are not careful, we might read these chapters in Proverbs as affirming a similar—unjust—perspective. It is easy to blame the woman involved for sexual sins and failings which are just as much if not more, those of the men involved, just as it is easy to overlook the socio-economic factors which often lure or drive a woman into using her sexuality as a means of survival, or as the ground of her value as a person.

Roland Murphy notes that the

Translations and understanding of the … “a foreign woman” and the … “a strange woman” vary considerably. The literal sense of the terms includes: stranger, outsider (outside of what? family, tribe, nation?), foreign, alien, another. A secondary meaning that may be derived from some contexts is adulteress. It is better to keep to the literal meaning wherever possible, and let other levels of meaning, if any, emerge in the course of chaps. 1-9 (Murphy, Proverbs (WBC), 13-14.

It may be that in ancient Israel, the foreign woman had no other means of survival than the sale of her body. Or perhaps she was alluring because different, and so perceived as a threat, especially if she also brought other gods and foreign worship with her. There may be xenophobic as well as sexual elements at work in this passage. In any case, the woman is portrayed in very negative terms: she is deceitful, uncaring and unstable (vv. 4-6), and the sons are warned in very strong language to have nothing to do with her.

The warnings in this passage have to do with consequences. Those who frequent the door of this woman will give their “strength” to strangers, their years to “the cruel one.” Strangers and aliens will receive their hard-earned wealth, their flesh and their body will be consumed, and their final years will be filled with isolation, regret and reproach (5:7-14). Poverty, bitterness, shame, and perhaps even disease will await those who indulge in her pleasures.

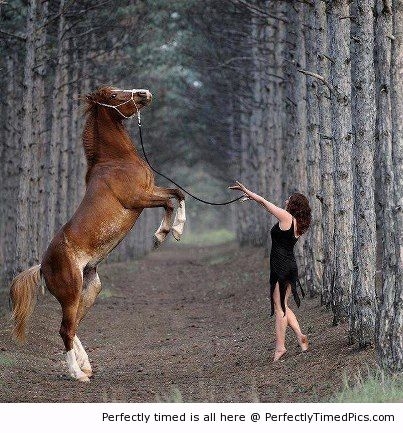

In this context, then, the positive marital-sexual vision of verses 15-20 is set forth. Here the language is that of abundance, of a well-watered garden—a very rich and evocative image in a desert landscape. Not simply evocative, the language is overtly erotic, “wells” and “fountains” imaging the female and the male sexual partners. It seems likely that the partners have been married for some time since the passage refers to the husband’s wife as “the wife of your youth” (v. 18; Cf. Ecclesiastes 9:9). As already noted, the addressee of the passage is especially the man, who is admonished to be satisfied in her love, with her breasts, to view her in terms of the grace and vigour of a doe. He is to drink water from his own cistern—not that of others—and likewise, keep his streams “out of the streets.” He is to rejoice in his wife, and she evidently, in her husband. Their congress is a joyful meeting, unrestrained and, one hopes, mutually exhilarating. She remains the only object of his sexual desire through the years, the only well from which he draws water, the only guest to visit his fountain.

In this context, then, the positive marital-sexual vision of verses 15-20 is set forth. Here the language is that of abundance, of a well-watered garden—a very rich and evocative image in a desert landscape. Not simply evocative, the language is overtly erotic, “wells” and “fountains” imaging the female and the male sexual partners. It seems likely that the partners have been married for some time since the passage refers to the husband’s wife as “the wife of your youth” (v. 18; Cf. Ecclesiastes 9:9). As already noted, the addressee of the passage is especially the man, who is admonished to be satisfied in her love, with her breasts, to view her in terms of the grace and vigour of a doe. He is to drink water from his own cistern—not that of others—and likewise, keep his streams “out of the streets.” He is to rejoice in his wife, and she evidently, in her husband. Their congress is a joyful meeting, unrestrained and, one hopes, mutually exhilarating. She remains the only object of his sexual desire through the years, the only well from which he draws water, the only guest to visit his fountain.

The possibility of such an idyll seems remote in the present. The prevalence of divorce, adultery, and promiscuity, the existence of Ashley Madison (“Life is short; have an affair”), the globalisation of the sex trade, and the pervasive sexualisation of our media all demonstrate a culture in thrall to disordered sexuality, as well as the loss of a positive marital vision. “I sex, therefore I am” may capture the contemporary western vision of what it means to be human. Such a terribly oppressive philosophy can only multiply the number of victims in a brutal world of dog-eats-dog, where winners are few and the disenfranchised are discarded.

The monogamous vision of this proverb is oft decried today, viewed as quaint, unrealistic and sometimes as oppressive. It is also true that it is an ideal many fail to live up to, despite their best intents, for monogamy is difficult, especially in a sexualised world. Still, the vision must be upheld, otherwise we will lose sight of the biblical wisdom it proclaims: that sex is God’s good gift to men and women, that sex is a means and never an end, that sex belongs and ultimately can only thrive in a covenantal context, that sexual union images the fruitful and faithful union of Christ and his church, and of God and his people.

Removed from this context and vision sex becomes a destructive and enslaving power: his own iniquities will capture the wicked, and he will be held with the cords of his sin. Sex, like other creational goods, can become an idol, an obsession and an addiction. This proverb would have us retain our strength and avoid the personal, familial and cultural dissolution that results from unrestrained sexual practice. It honours the marriage bed and keeps it a private garden of delight for husband and wife alone. It calls men, especially, to restrain their sexual proclivities and remain faithful and satisfied with the wife of their youth. And it calls husbands and wives to an idyllic vision, and so to a mutual intention and commitment toward the realisation of that one-flesh vision in their own lives.

In this context, then, the positive marital-sexual vision of verses 15-20 is set forth. Here the language is that of abundance, of a well-watered garden—a very rich and evocative image in a desert landscape. Not simply evocative, the language is overtly erotic, “wells” and “fountains” imaging the female and the male sexual partners. It seems likely that the partners have been married for some time since the passage refers to the husband’s wife as “the wife of your youth” (v. 18; Cf. Ecclesiastes 9:9). As already noted, the addressee of the passage is especially the man, who is admonished to be satisfied in her love, with her breasts, to view her in terms of the grace and vigour of a doe. He is to drink water from his own cistern—not that of others—and likewise, keep his streams “out of the streets.” He is to rejoice in his wife, and she evidently, in her husband. Their congress is a joyful meeting, unrestrained and, one hopes, mutually exhilarating. She remains the only object of his sexual desire through the years, the only well from which he draws water, the only guest to visit his fountain.

In this context, then, the positive marital-sexual vision of verses 15-20 is set forth. Here the language is that of abundance, of a well-watered garden—a very rich and evocative image in a desert landscape. Not simply evocative, the language is overtly erotic, “wells” and “fountains” imaging the female and the male sexual partners. It seems likely that the partners have been married for some time since the passage refers to the husband’s wife as “the wife of your youth” (v. 18; Cf. Ecclesiastes 9:9). As already noted, the addressee of the passage is especially the man, who is admonished to be satisfied in her love, with her breasts, to view her in terms of the grace and vigour of a doe. He is to drink water from his own cistern—not that of others—and likewise, keep his streams “out of the streets.” He is to rejoice in his wife, and she evidently, in her husband. Their congress is a joyful meeting, unrestrained and, one hopes, mutually exhilarating. She remains the only object of his sexual desire through the years, the only well from which he draws water, the only guest to visit his fountain.