Chapter Four: Spirit Baptism in Trinitarian Perspective (Cont’d)

Chapter Four: Spirit Baptism in Trinitarian Perspective (Cont’d)

Macchia considers the Baptism with the Holy Spirit in its trinitarian dimensions, first by reflecting on the significance of Jesus as Spirit-baptiser for an understanding of his divinity. Macchia suggests that Jesus’ resurrection alone is not sufficient to assert his divinity, but that his role as Spirit-baptiser also supports this claim, for only God can give God (110-111). If the risen Jesus gives the Spirit who is also God, then Jesus, too, must be divine. He was raised to be the Spirit-baptiser, the one who give the life-giving, life-transforming eschatological Spirit.

Without the role of Jesus as the one who bestows the Spirit, his resurrection would have lost its eschatological goal and the relationship of Jesus to his heavenly Father would have lost its strongest clue (111).

Second, BHS is itself a trinitarian act, being the inauguration and advancement of the cosmic and eschatological reign of the Father by the Son and in the Spirit. Through Jesus Christ, the breath of the Father is proceeding to all creation animating and renewing it that it may return to the Father in the Spirit and through Christ. In Spirit-baptism the triune God opens his life to embrace, gather and indwell the creation. Macchia is clearly influenced by Moltmann in this discussion as he grounds his discussion of the triune life in the biblical narrative of Jesus’ life, and adopts a relational view of the trinity.

Spirit baptism accents the idea that the triune life of God is not closed but involved in the openness of self-giving love. … The reign of God comes on us through an abundant outpouring of God’s very Spirit on us to transform us and to direct our lives toward Christlike loyalties. From the trinitarian fellowship of the Father and the Son, the Spirit is poured out to expand God’s love and communion to creation (116).

Macchia attempts to side-step the question of the inner life of the triune God (125), but still favours a social trinitarianism that yet maintains an economic monarchy of the Father in which the “Son and the Spirit share the monarchy of the Father in mutual dependence and working in a way that implies the Father’s dependence on them as well. … Spirit baptism in the context of the inauguration of the kingdom of God means that the Father’s divine monarchy is not abstract but mediated by the Son and the Spirit in the redemption of the world” (124). God the Trinity is open to the world including human suffering:

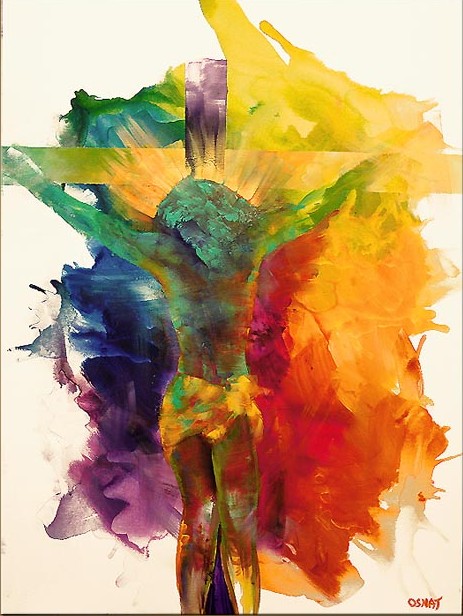

In Spirit baptism, God seeks to tabernacle with creation in empathy with the suffering creation and toward its final liberation. After all, the Spirit of Spirit baptism is the one who groans with the suffering creation for its eventual liberation through Christ. Spirit baptism reveals profoundly what is implied in the incarnation and the cross (126).

Macchia brings this long chapter to a conclusion by considering Spirit-baptism in relation to the primary elements of Christian life which he identifies as justification, sanctification and empowerment. Although “Spirit-baptized justification” includes an alien element—that is, the gift of righteousness given to the believer by God ever remains grounded externally in Christ as his righteousness rather than our own—Macchia’s emphasis falls on justification’s transformative elements: through faith in Jesus the believer receives the Holy Spirit and so is united with Christ, is granted the imputation of his victory over sin and death, and thus participates in the new creation. Justification, in Macchia’s vision of the Spirit, is not simply a legal or forensic act which leaves believer unchanged, but includes the regenerating and sanctifying work of the Spirit. To be justified is to be “righteoused” by God (130). The “righteousness” involved in justification is a liberating and redemptive concept that reorders life toward justice and mercy (132).

Justification loses connection with the full breadth of its concrete substance in the life of Jesus as the Spirit-anointed Inaugurator of the kingdom of God if it is defined essentially as an abstract declaration realized in a juridical transference of merits (138).

Justified existence is thus pneumatic existence, Spirit-baptized existence. … In the here and now, the righteousness of justification produces a life dedicated to the reign of God on earth, to the weighty matters of the law, to reconciled and reconciling communities of faith, and to the justice and mercy of God in the world (139).

Turning his attention to “Spirit-baptized sanctification” Macchia insists that justification and sanctification are not two sequential aspects of Christian life, but the entirety of Christian life portrayed by one or the other of these two overlapping metaphors (140). Spirit-baptized sanctification concerns participation by the Spirit in the consecration of Jesus to the Father for the world, in solidarity with their misery. Sanctification refers primarily to an objective accomplishment through the Spirit as a sanctifying presence.

Like Jesus, the disciples were sanctified for faithfulness in the world and not for escape from the world (Jn. 17:15-16). Their sanctification and consecration was unto a holy purpose that required their engagement with the world, not their avoidance of it. If Jesus fulfilled all righteousness by bearing the burdens of the sinners, how can we interpret kingdom sanctification as an avoidance of the sinners? (143-144)

Finally, “Spirit-baptized witness” concerns charismatic or vocational empowerment for the service and witness of the kingdom. If sanctification implies being set apart for a holy task, empowerment is being granted the capacity for the fulfilment of it.

The sanctifying work of the Spirit needs to be released in life through powerful experiences of renewal and charismatic enrichment that propel us toward vibrant praise, healing reconciliations, enriched koinonia, and enhanced gifting for empowered service (145).

Macchia rightly identifies this idea as an essential aspect of the Spirit’s work in Christian life, and a particular contribution Pentecostalism can make to the wider Christian family. Christian initiation must include, says Macchia, a sense that the grace of God gifts Christians for ministry and mission (151). “There is no Christian initiation by faith and baptism in the full sense of the word without some sense of commissioning to service” (156). In this respect, Spirit-baptism as the initiation of Christian life indicates the inherently missional character of Christian identity. Nevertheless, the work of the Spirit is not simply initiatory but progressive and eschatological. Therefore, Christians may and indeed must, continually seek for a greater fullness of the life of the Spirit, anticipating fresh experiences of the Spirit’s sanctifying and empowering presence, so that they might truly participate in the life of God’s kingdom.