Mark’s Passion Narrative (7)

Mark sets the Last Supper between two passages that speak of betrayal, desertion, and denial. The covenant meal which symbolises unity and participation with Jesus, covenant loyalty and faithfulness, covenant friendship and intimacy, is contrasted with prophecy of personal betrayal. Jesus will be abandoned by his own: betrayed by one friend, deserted by others, and denied—three times!—by Peter. You can read this passage in Mark here.

Amongst devout Jews, the Passover concluded with the so-called Hallel Psalms (Psalms 114-118). It is possible that Jesus and the disciples sang or recited these psalms as they finished their meal and prepared to go out to the Mount of Olives, something Jesus did regularly when in Jerusalem (Luke 21:37).

As they were going, Jesus announced to his disciples that they would all desert him—become offended, fall away, or be ‘scandalised.’ Jesus supports this assertion with an appeal to Scripture: ‘I will strike the shepherd and the sheep will be scattered.’

Jesus is quoting Zechariah 13:7 though suggesting that it is God who strikes the shepherd. In Zechariah it is an oracle against the wicked shepherds of God’s people. There the shepherd is struck so that the sheep may be scattered; that is, it is an oracle of judgement. Here, and the sheep will be scattered—is a consequence rather than intention. Nevertheless, the whole story of Jesus’ passion is unfolding in accordance with the divine purpose. His death is not the triumph of evil nor a tragic accident. Jesus gives his life as a ransom for many (10:45).

Jesus’ announcement that the disciples will desert him offends the disciples, especially Peter. The Greek word for ‘desert’ is skandalizesthai which in Mark denotes defection in the face of trial or persecution (e.g. Mark 4:17; 6:3; 9:42-47; see Lane, The Gospel of Mark, 509). When believers encounter trouble, trial, or persecution they are tempted to become offended: why is God allowing this to happen? I didn’t sign up for this!

Peter denies vehemently that he will desert Jesus: “Even if all become deserters, I will not.” I can’t help but wonder if there is an edge in Peter’s voice, a little competitiveness whereby he asserts his faithfulness over against that of his companions. In Luke’s account, we learn that a dispute arose amongst the disciples as to which of them was the greatest (Luke 22:24). And in John’s account of the washing of the feet, Jesus demonstrates what true greatness looks like, instructing the disciples in the nature of servant leadership for those in his community (John 13:1-20).

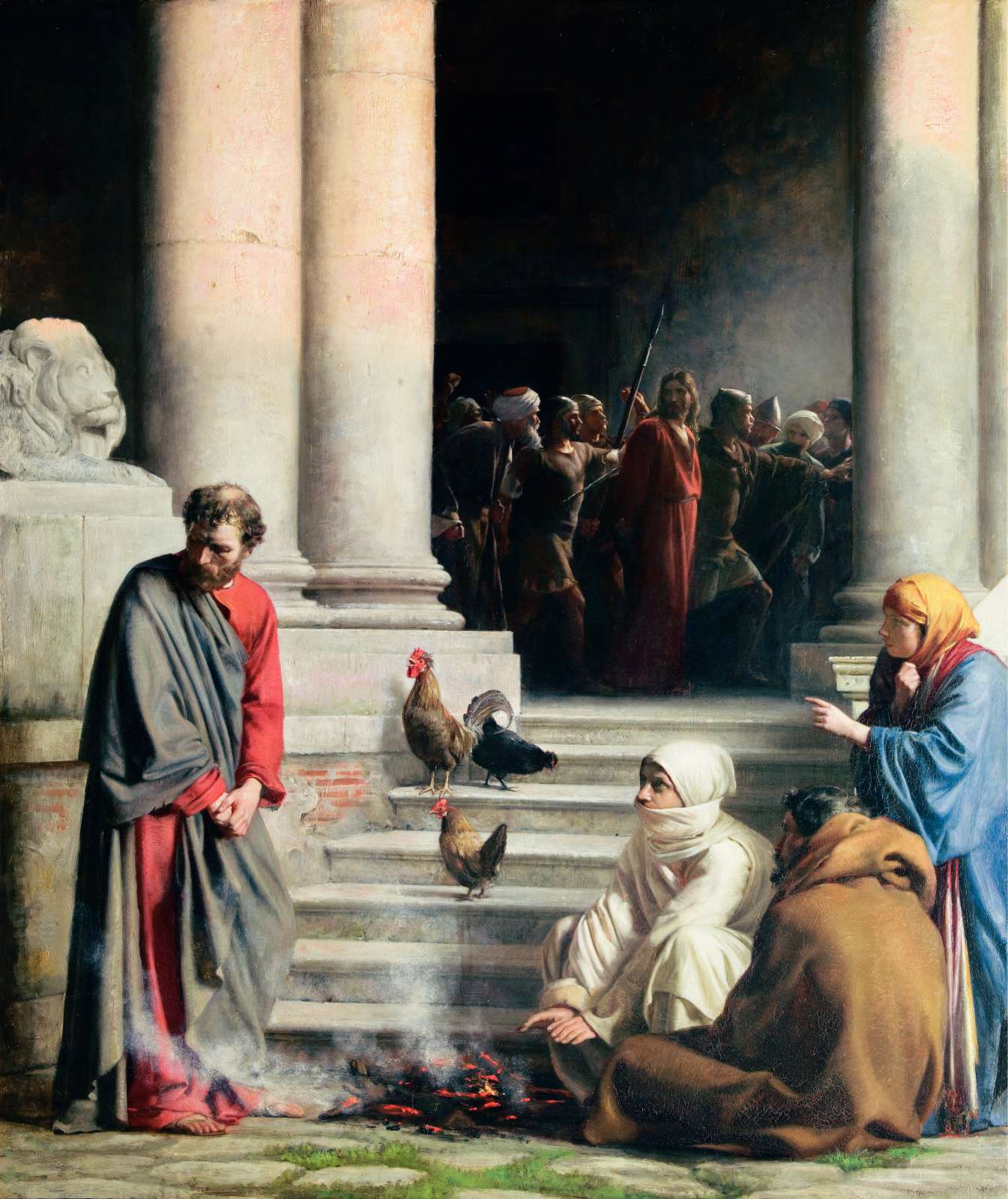

Although Peter claims much for himself, he too will fall away. Indeed, Jesus tells him bluntly that “this very night, before the cock crows twice, you will deny me three times.” Peter vehemently denies that he will deny Jesus; he corrects Jesus! “Even though I must die with you, I will not deny you.” Now, refusing to be outdone by Peter, all the others join in to assert the same of themselves. They all insist that they will not desert him, though as the narrative proceeds, they all do fall away.

Peter’s heart is to be true to Jesus: no doubt he means what he says. In his mind, denial is worse than death for honour is at stake. He has committed friendship and loyalty to this man—how could he deny him? But though his heart aspires to such heroic steadfastness, he will fall.

In this passage we see something of Mark’s insight into the passion of Jesus: “the passion story is not simply about the passion of Jesus, but the passion the community experiences in its living out of the gospel in the world” (Senior, The Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark, 63). What Jesus suffered for them they will also suffer for him. The disciples will be like their Master. This is the brutal truth, that in their association with Jesus they too will suffer as he did. Mark’s first readers in Nero’s Rome were finding this to be true and like Peter, would find their faith severely tested.

Part of Peter’s problem is that he did not listen carefully enough to Jesus, for Jesus had something more to say. Peter heard Jesus’ first statement by not his second. His abrupt announcement is immediately supplemented with a promise: ‘But after I am raised up I will go before you to Galilee.’ As with the defiant faith of verse 25, so here. Jesus death, the disciples’ desertion, and Peter’s denial are not the end of the story. Jesus will also be raised and will go ahead of them to Galilee. They will also go to Galilee—they who have deserted and denied him. “The scattered flock will be brought together again, under their shepherd’s leadership. In spite of their failure, the shepherd will still acknowledge his sheep” (Hooker, The Gospel According to St Mark, 345). They will be forgiven and restored, gathered and unified, and made participants once more in his cause.

The word proagõn ‘to go ahead of’ or ‘lead’ used in 10:32 is identical with the words found in 14:28 (“I will go before”) and 16:7 (“he is leading”). The three verses together are a distillation of Mark’s entire theology: the Son of Man who leads the fearful community of disciples from Galilee to Jerusalem and who will also go ahead of them through death to victory, is the same compassionate and now triumphant Son of Man who will restore his broken followers to discipleship and lead them back to Galilee. “Galilee” is the place of the universal mission, but no disciples are ready to proclaim the Gospel there until they have walked the road to Jerusalem and encountered the reality of the cross (Senior, The Passion, 66).