Teaching and learning theology is dangerous: so says Neder in his fourth chapter. Of course, teaching spaces should be ‘safe spaces’ in the sense that students are not demeaned, coerced, or manipulated. Unless students have confidence that teachers and classmates take their questions and ideas seriously they are unlikely to learn much.

Teaching and learning theology is dangerous: so says Neder in his fourth chapter. Of course, teaching spaces should be ‘safe spaces’ in the sense that students are not demeaned, coerced, or manipulated. Unless students have confidence that teachers and classmates take their questions and ideas seriously they are unlikely to learn much.

But it’s also true that if students feel only affirmed in our classes, if our classes never disturb, unsettle, or expose them, if they never find themselves fighting for their lives, then they probably aren’t going to learn much in that kind of environment either (85).

The atmosphere of our classes ought to cohere as much as possible with the reality we are attempting to describe. And since Christian theology occurs as an encounter with the living God, a confrontation that tears us away from patterns of life that obscure or contradict the truth, at least something of the spirit of that struggle ought to be reflected in our classrooms (86).

Neder takes Isaiah’s visionary call as paradigmatic (Isaiah 6), though this is something that occurs in the divine-human encounter, something that can never be manufactured and should never be coerced. It is the subject matter—God!—who confronts the student with a call to decision, not the teacher. Nevertheless, seeking to know God or to teach in such a way that God might be known is risky. When God confronts us, we are stripped of our defences and called to decision—here and now! Christ disturbs and disrupts. He calls us ‘out’ of our own lives and into his life; he is unpredictable. Indeed, “following Jesus hurts” (98). Jesus wounds, in order to heal (95).

Conversations with Jesus rarely unfold according to plan. Jesus continually shocks and astonishes people, rattles their cages, upends their expectations, eludes their traps, and zeroes in on their deepest motivations. This makes for exhilarating reading, but the more you reflect on it, the more unsettling it becomes. . . . You begin to realize that being near him requires courage (96).

This is not to suggest that teachers should set out to disrupt or deconstruct their students’ supposedly naïve faith—such an approach is confused and contemptible. Teaching theology is an act of love; teachers are to help students perceive and respond to the truth, not scandalise or provoke them (99-100). Indeed, teachers cannot reliably discern precisely what is occurring in the hearts and lives of their students. “If students hate your classes,” Neder says wryly, “it’s probably your fault” (89). But that they enjoy your classes and are attentive and engaged does not mean that they have been engaged by the ‘subject matter.’ “Can you think of anything more inane than a Christian theologian who thinks his or her classes are successful just because everyone likes them and no one feels uncomfortable?” (89)

Students can seek theological certainty rather than God; or theological speculation or endless deliberation. They may consider doctrinal or historical exploration or clarification as sufficient in themselves. If students think like this, it may be that they have learnt it from their instructors.

We instruct students not only by what we say about God but also by how we speak about him. . . . If our way of talking about God leaves students unaware of the threat he poses to our lives, perhaps that is because we no longer perceive the threat he poses to our lives (101).

Yet the knowledge of God requires decision and commitment, and students themselves must embrace this risk. Christianity simply cannot be reduced to doctrines (or history or morality or a hundred other things we might substitute for it). Rather,

Christian existence conditions the plausibility of Christian speech . . . either our teaching . . . will suggest God’s urgent uncontrollable presence with us, his ‘terrifying nearness’ as Bonhoeffer put it, or our teaching will mislead students. There are no exceptions to this rule (103).

“Real theological education is a process of continual confrontation with God. To receive it, students have to fight for it themselves” (108).

It is clear in this chapter that Neder believes true theological education occurs when students are confronted with the reality of God—and called to decision. It also seems clear that this is not the work of the theological educator. The best they can do is hope that God is at work in their teaching, pray for it, engage in authentic theological existence in their own lives, and continually bear witness to God in their teaching.

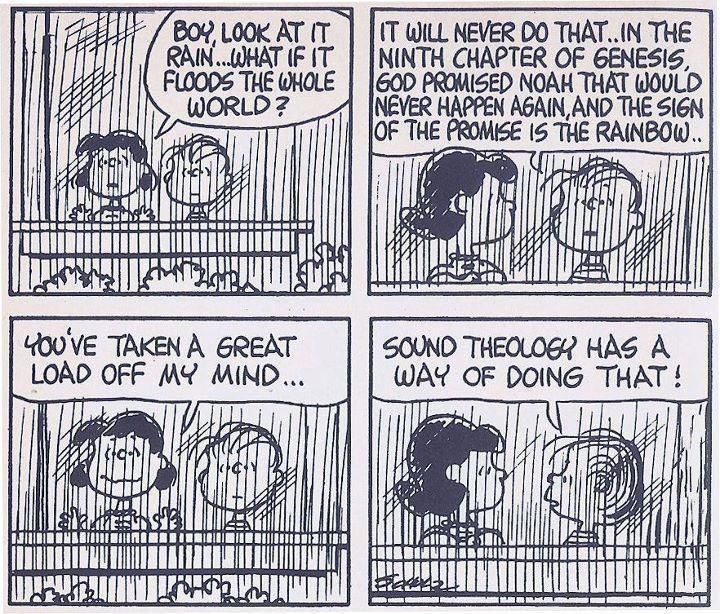

The final chapter (“Conversation”) describes the process of teaching and learning theology: “teaching Christian theology is largely a matter of training students to have good theological conversations” (118).

Christian theology is a historically extended conversation about the meaning and implications of the gospel. It is thinking and speaking that seeks to respond in disciplined, faithful, and creative ways to God’s own self-communication (118).

The primary—fundamental and essential—conversation is with Holy Scripture itself, seeking ever and again to hear and respond to the testimony of the prophets and apostles. But this conversation requires a secondary conversation with other readers and interpreters past and present—a conversation conducted for the sake of the primary conversation. Neder insists that good teachers train students to read with sympathetic attention rather than the habits of suspicion and scepticism which characterises contemporary study in the humanities (121-122).

Despite its hegemony, there are strong theological (and non-theological) reasons to be suspicious of ubiquitous suspicion—not least of which is that suspicious readers don’t generate conversations as interesting and fruitful as do readers who befriend the texts they interpret (123).

The book closes with a brief section on cultivating classroom conversations. “Conversations reveal commitments that require closer examination, beliefs that need to be sharpened or discarded, assumptions that cannot withstand sustained scrutiny” (132). Neder finds a model for theological reflection in the kinds of questions Jesus posed to his interlocutors: questions that probe and personalise theological reflection, that penetrate to the heart of students’ deepest concerns (136-137). Good conversations occur in classrooms that are genuine learning communities—where teachers also expect to learn from their companions in the conversation. Such conversations require deep, patient, and careful listening to one another in an atmosphere of critical inquiry, grace, respect, and courtesy. They require honest discussion of one’s own ideas, an openness to new or other ideas, profound personal questions, and a stimulating breadth of opinion.

But conversation is not an end in itself:

Its purpose is to help students encounter the truth, discover their lives in Christ, and follow him into the world he loves. If the conversations that take place in our classes have the opposite effect on students, if students acquire the habit of talking about God objectively and dispassionately, if they come to believe that the truth can be known without being lived, learned without being appropriated, and if the accumulation of theological ideas results not in existential transformation and faithful witness but in endless talking and permanent postponement of decision and action, then our teaching works against the work of the Holy Spirit (143).