The Knowledge of God

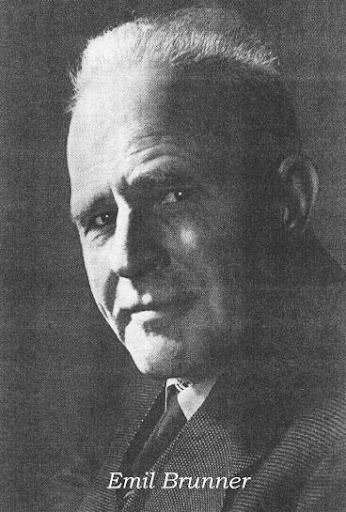

Brunner’s first three meditations concern the knowledge of God: Is there a God? Is the Bible the Word of God? and the Mystery of God. Brunner wants to turn the first question on its head. To even ask the question is to signify a fundamental disconnect between ‘ourselves’ and our heart, conscience, and awareness of the world, all of which testify to the reality of God. “Your heart knows something of God already; and it is that very knowledge which gives your question existence and power” (Brunner, Our Faith, 14). Further, “not only the heart within, but the world without also testifies of God” (14-15).

Brunner’s first three meditations concern the knowledge of God: Is there a God? Is the Bible the Word of God? and the Mystery of God. Brunner wants to turn the first question on its head. To even ask the question is to signify a fundamental disconnect between ‘ourselves’ and our heart, conscience, and awareness of the world, all of which testify to the reality of God. “Your heart knows something of God already; and it is that very knowledge which gives your question existence and power” (Brunner, Our Faith, 14). Further, “not only the heart within, but the world without also testifies of God” (14-15).

To ask the question, then, “Is there a God?” is to fail to be morally serious. For when one is morally serious one knows that good is not evil, that right and wrong are two different things, that one should seek the right and eschew the wrong. There is a divine order to which one must bow whether one likes to do so or not. Moral seriousness is respect for the voice of conscience. If there is no God, conscience is but a complex of residual habits and means nothing. If there is no God then it is absurd to trouble oneself about right—or wrong (15-16).

Like Calvin, Brunner presupposes an innate knowledge of God, supported by an external knowledge of God grounded in the created order. “That God exists is testified by reason, conscience, and nature with its wonders. But who God is—God Himself must tell us in His Revelation” (16, original emphasis). This ‘natural’ knowledge of God (shared by all humanity) is really an awareness of something more rather than personal knowing. One does not know God in a personal or relational sense but ‘knows’ of God or has an intuition of his reality. The reason for this is that God is not ‘a thing’ in this world, one more thing amongst other things, an object of knowledge which might be discovered and categorised and thereby mastered by the knower (13). God, rather, intends that we might know him and be mastered by him.

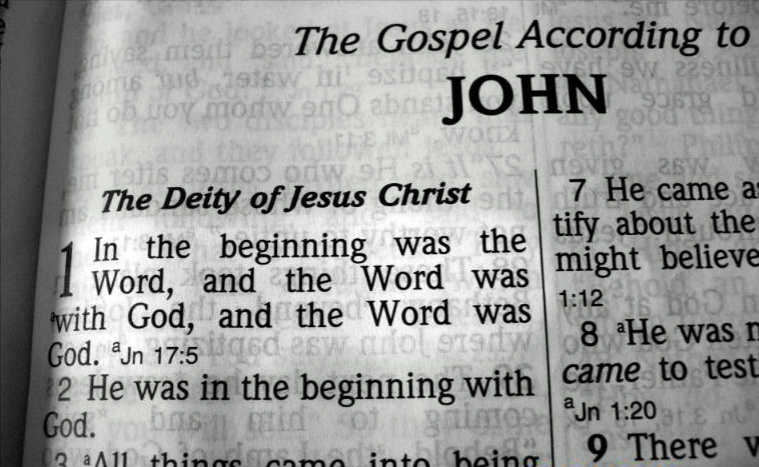

It is for this reason that God has given us the Bible: “God has made known the secret of His will through the Prophets and Apostles in the Holy Scriptures. He permitted them to say who He is” (18). Brunner holds an instrumental view of the Scripture. God speaks to humanity through the Bible. It is the Word of God because and as it points to Jesus Christ, and because in it we hear the voice of God. The Bible speaks in many ways of its one central theme—of the Good Shepherd God who comes to us. “The voices of the Prophets are the single voice of God, calling. Jesus Christ is God Himself coming. In Him, ‘the word became flesh.’ … He is the Word of God” (19, original emphasis). Brunner uses the analogy of a gramophone record and the record label “His Master’s Voice” to illustrate how the Scripture functions as the Word of God. (I remember as a child my father’s record collection included albums from this label!)

If you buy a gramophone record you are told that you will hear the Master Caruso. Is that true? Of course! But really his voice? Certainly! And yet—there are some noises made by the machine which are not the master’s voice, but the scratching of the steel needle upon the hard disk. But do not become impatient with the hard disk! For only by means of the record can you hear ‘the master’s voice.’ So, too, is it with the Bible. It makes the real Master’s voice audible—really His voice, His words, what He wants to say. But there are incidental noises accompanying, just because God speaks His word through the voice of man. … But through them God speaks His word. … The importance of the Bible is that God speaks to us through it (19-20).

What the Bible reveals is Jesus Christ—the mystery of who God is. All that humans can know in their own capacity is the world. God, however, is not the world but rather the mystery within which the world has its being (21). The mystery of God is threefold: his transcendent majesty over the world, his searing holiness which wills our obedience, and his unspeakable love and condescension. In his transcendent majesty, God is Lord. He is the Almighty whose holy will confronts us as an absolute to which we must either submit ourselves or against which we will shatter ourselves.

But the mastery of God is even greater. The will of this holy God—what He absolutely desires, is love. His feeling towards us is of infinite love. He wants to give Himself to us, to draw and bind us to Him. Fellowship is the one thing He wants absolutely. God created the world in order to share Himself. … God desires one thing absolutely: that we should know the greatness and seriousness of His will-to-love, and permit ourselves to be led by it. Our heart is like a fortress which God wants to capture (22-23).

Brunner’s portrayal of the divine mystery posits the sheer givenness of God’s transcendence: God simply is and is the almighty and holy God. This is the overarching reality within which our being and the being of the world has its being. The central category Brunner uses to discuss God’s relation to the world is the divine will. Brunner speaks first of the holiness and demand of God and only then of the tender lovingkindness of God. In each case it is a matter of the divine willing, and in each case the divine will is absolute. Yet although Brunner speaks of the divine holiness first, it seems that the divine loving has a deeper and perhaps more fundamental bearing: God created the world in order to share himself with it, and wills above all things that we should know his ‘will-to-love.’

Our heart is like a fortress which God wants to capture. He wants to capture it with His love. If, overcome by His love, we open the gate, it is well with our souls. If, however, we obstinately close our hearts to His love, His absolute will—then woe to us! If we refuse to surrender to the love of God, we must feel the absoluteness of His will as wrath (23-24).