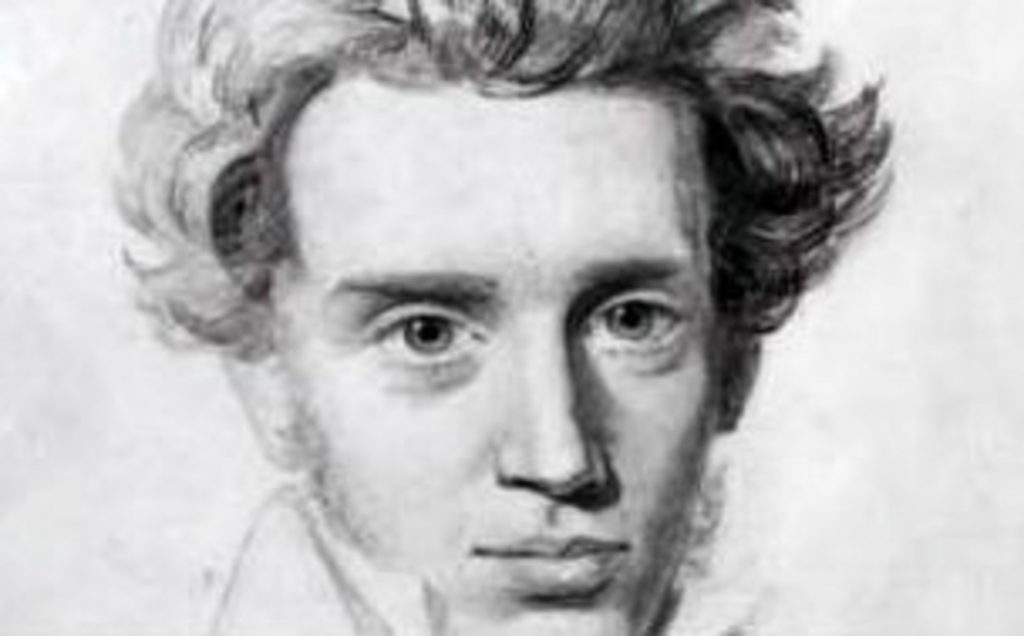

I found this marvellous quote from Kierkegaard in Richard Bauckham’s monograph on James:

I found this marvellous quote from Kierkegaard in Richard Bauckham’s monograph on James:

Christian scholarship is the human race’s prodigious invention to defend itself against the New Testament, to ensure that one can continue to be a Christian without letting the New Testament come too close.

Bauckham cites Kierkegaard, and does so at the start of each chapter of his book because the first chapter of James was the Danish philosopher’s favourite chapter. He recognises Kierkegaard’s comment as an over-reaction, as a statement of hyperbole, necessary as a corrective, but an over-reaction all the same (Bauckham, James, 8).

He identifies Kierkegaard’s real target as the isolation of biblical studies, or more particularly, the biblical scholar, from subjective engagement with the biblical text. The aim of nineteenth-century biblical interpretation by means of historical criticism was the establishment of the objective meaning of the text, independent of confessional and dogmatic presuppositions. In Bauckham’s view, biblical scholarship has failed in its attempt to reach this goal. (I might note that many evangelical scholars also aim at establishing the objective meaning of the text, though by means of a different method.)

The trouble with the quest for objectivity, as understood by Kierkegaard in his own day, is that one relates to the Bible but not to Scripture. Such scholarship faces, and often succumbs to, the temptation to substitute study for faith and obedience. One only reads Scripture as Scripture if one takes it to heart and lives it.

One reason Kierkegaard appreciated James 1 was because of James’ use of the mirror analogy. The concern Kierkegaard has with Christian scholarship is that in the quest for objectivity, scholars spend their time examining the mirror. The purpose of a mirror, however, is not to examine the mirror itself, but to look at oneself. Thus Kierkegaard warns the scholar:

If you are a scholar, remember that if you do not read God’s Word in another way, it will turn out that after a lifetime of reading God’s Word many hours every day, you nevertheless have never read—God’s Word.

Kierkegaard suggests that this is, in fact, the intent of Christian scholarship: to keep God’s Word at bay, so that it is not heard, so that one is not confronted by its claim and its command, so that one can continue as a Christian without hearing and taking to heart its message. Christian scholarship achieves this by raising so many questions about the text, about its context, about its interpretation, so many “new lines of supposedly objective enquiry that its effect is to postpone faith and obedience to God’s word indefinitely” (Bauckham, 3).

But our world is very different to that inhabited by Kierkegaard, and so, in a stunning adjustment, Bauckham has updated Kierkegaard’s provocation for our own age:

Biblical scholarship is the human race’s prodigious invention to defend itself against the New Testament, to ensure that one can continue to be a Christian without letting the New Testament come too close, or to ensure that one can continue not to be a Christian by not letting the New Testament come too close (Bauckham, James, 2).