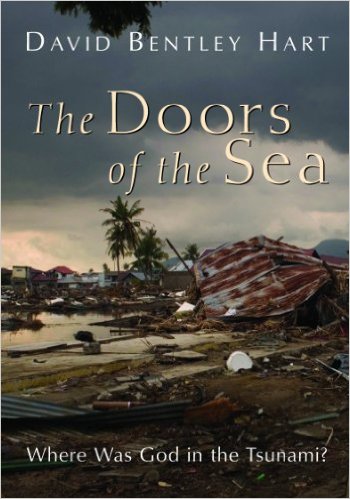

Although just 104 small format pages, there is much to admire in this book. This, my first foray into a David Bentley Hart book, was intended as some brief light reading in the midst of a busy semester programme. It took only a page or two to disabuse me of this assumption. Hart is a literary artist, a man of letters, exhibiting a breadth of knowledge encompassing diverse disciplines and several languages, writing with a beautiful, literary hand, all the while straining and extending not only the limits of my vocabulary but those of my theological vision as well.

Although just 104 small format pages, there is much to admire in this book. This, my first foray into a David Bentley Hart book, was intended as some brief light reading in the midst of a busy semester programme. It took only a page or two to disabuse me of this assumption. Hart is a literary artist, a man of letters, exhibiting a breadth of knowledge encompassing diverse disciplines and several languages, writing with a beautiful, literary hand, all the while straining and extending not only the limits of my vocabulary but those of my theological vision as well.

The book had its origin days after the devastating Boxing Day Tsunami in the Indian Ocean, when Hart wrote a small piece entitled “Tremors of Doubt” for the Wall Street Journal on Friday December 31, 2004. A longer article appeared in First Things in March 2005, with this book coming to press shortly afterwards, born as it were, on account of the response his initial article generated. Hart wonders whether, in fact, he should have spoken at all; surely the most apt response to such devastation would have been to remain silent? (6, 92) Yet he does not:

I still find myself less perturbed by the sanctimonious condescension of many of those who do not believe than by either the gelid dispassion or the shapeless sentimentality of certain of those who do. (92)

Thus the book is both a reflection on the critical issues of God’s goodness and sovereignty in light of this catastrophe, and a polemic against what Hart considers to be defective views of these very same issues.

Universal Harmony

The Doors of the Sea contains just two chapters—“Universal Harmony” and “Divine Victory”—each comprising five short sections. The first chapter surveys various responses to the tsunami, and varieties of such responses to other tragedies in history. He takes aim first at those vocal atheists who used the devastation and consequent suffering of the tsunami to “prove” there is no God. For Hart,

There is no argument here to refute; the entire case is premised upon an inane anthropomorphism—abstracted from any living system of belief—that reduces God to a finite ethical agent, a limited psychological personality, whose purposes are measurable upon the same scale as ours, and whose ultimate ends for his creatures do not transcend the cosmos as we perceive it. (13)

Although the arguments of Christianity’s critics have emotional and even moral force, they are utterly bereft of logical force. In a wry conclusion Hart states, “For the secret irony pervading these arguments is that they would never have occurred to consciences that had not in some profound way been shaped by the moral universe of a Christian culture.” (15)

For, if we are honest in asking what God this is that all our skeptics so despise, we must ultimately conclude that, while he is not the God announced by the Christian gospel, he is nevertheless a kind of faint and distorted echo of that announcement. It is Christianity that not only proclaimed a God of infinite goodness but equated that goodness with infinite love. The atheist who argues from worldly suffering, even crudely, against belief in a God both benevolent and omnipotent is still someone whose moral expectations of God—and moral disappointments—have been shaped at the deepest level by the language of Christian faith. (24-25)

Though this line of argument might give some superficial comfort to Christians, this is not Hart’s intent. Worse than the rants of shallow atheists and the protests of Voltaire against a deist God, are those Christian “explanations” of evil that seem to justify the evil and suffering by appeal to some kind of eschatological calculus, whereby the ultimate purposes of God will make all this suffering along the way somehow “worth it,” as though divine ends justify the most horrific means (see 25-29). Here, and throughout the book, Hart takes particular aim at certain versions of Reformed theodicy.

It may seem…that I have made Calvinism into my particular bête noire, though that was never my intention. In part, this merely reflects the reality that, after the appearance of my column, those among its critics who exhibited the most exuberant callousness regarding the dead—even all those tens of thousands of dead children—and who reacted with the greatest belligerence and most violent vituperation to any suggestion that God might not be the immediate cause of all evil in the world were all Calvinists of a particularly rigorist persuasion. (92-93)

So Hart rails against every form of explanation that justifies the evil, the suffering, the tragedy, or the darkness which afflicts creation and history by appeal to some final balancing of accounts. There can be no final resolution which ultimately explains evil and suffering such as to remove its offence and thereby make it meaningful. Certainly God can bring about his good ends even in spite of evil (29), but for Hart, God is not in any way implicated in the evil itself, and especially by schemas which predicate the entirety of history on the outworking of the pre-determined divine will.

Such a God, at the end of the day, is nothing but will, and so nothing but an infinite brute event; and the only adoration that such a God can evoke is an almost perfect coincidence of faith and nihilism. Quite apart from what I take to be the scriptural and philosophical incoherence of this concept of God, it provides an excellent moral case for atheism. (30)

The hero in this search for universal harmony turns out to be Dostoyevsky, for whom there is no explanation of or justification for suffering—and so no universal harmony, rationally conceived, either. For Hart, Dostoyevsky makes a Christian prophetic protest: if the cost of eschatological shalom is all the suffering endured in and by creation—or even simply the suffering of one innocent child—the price is too high.

Whatever the case, for the Christian, [Dostoyevsky’s] argument—taken simply in itself—provides a kind of spiritual hygiene: it is a solvent of the liberal Protestantism of the late nineteenth century, which succeeded in confusing eschatological hope with progressive social and scientific optimism, and a solvent as well as of the obdurate fatalism of the theistic determinist, and of the confidence of rational theodicy, and—in general—of the habitual and unthinking retreat of most Christians to a kind of indeterminate deism. And this, again, marks it as a Christian argument, even if Christian sub contrario, because in disabusing believers of facile certitude in the justness of all things, it forces them back toward the more complicated, “subversive,” and magnificent theology of the gospel. [Dostoyevsky’s] rage against explanation arises from a Christian conscience. …

Voltaire sees only the terrible truth that the history of suffering and death is not morally intelligible. Dostoyevsky sees—and this bespeaks both his moral genius and his irreducibly Christian view of reality—that it would be far more terrible if it were. (43-44)

(Continued on Thursday…)