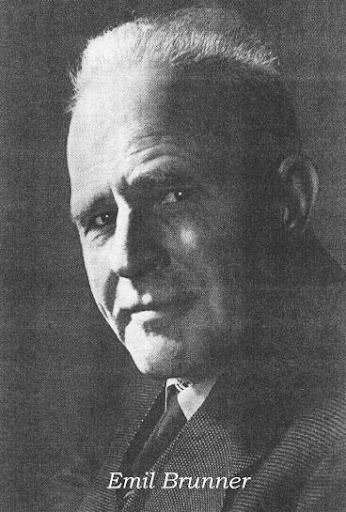

Brunner’s Natural Theology

It is clear in this section that Brunner presupposes a universal knowledge of God, natural in the sense that every person has some ‘instinct’ (53) for it, that the gift of conscience has been given to every person by God, that “the law of God is as though it had been engraved in the human heart” (46). “Even the heathen know faintly that this life is a gift of God the Creator” (56). And they know also that they have violated God’s law and ordinances.

It is clear in this section that Brunner presupposes a universal knowledge of God, natural in the sense that every person has some ‘instinct’ (53) for it, that the gift of conscience has been given to every person by God, that “the law of God is as though it had been engraved in the human heart” (46). “Even the heathen know faintly that this life is a gift of God the Creator” (56). And they know also that they have violated God’s law and ordinances.

Everyone has a bad conscience whenever he thinks about God, for we know quite well what God wants of us, and our own failure to do what He demands. We know that we are disobedient. But because we know … we flee from God, we hide from Him like Adam and Eve after the Fall. The Law of God drives us away from God, or, more correctly, our bad conscience drives us away. We do not fear God, but we are afraid before God. … A bad conscience and the law of God belong together. We have a bad conscience because we know the law of God (55).

Evident in this citation is Brunner’s emphasis of human responsibility before God, of a final accounting before the Judge. “God requires an accounting. He holds us responsible. And that is what strikes terror in us, for how can we bribe the judge in this case?” (47)

The spring of life is really poisoned, things are bad with us. This is the testimony of conscience and even more sharply and clearly, the testimony of Holy Scripture. Behind God’s command stands the fearful word—Judgment! Lost! It is written more sharply in the New Testament than in the Old Testament. What then are we to do? (51, original emphasis)

A question we might ask is whether Brunner has correctly assessed the human condition or whether, in fact, his analysis is predicated on the loss of the cultural knowledge of God in Christendom. His exposition is not uncommon but follows a long tradition of biblical interpretation, especially passages such as Romans 1-2. His doctrine echoes that of Calvin and the Reformed tradition’s distinction between general and special revelation. Nonetheless, his rhetoric seems to presuppose the conditions of European Christendom.

Further evidence of this suggestion arises from Brunner’s discussion of the divine ordinances. He speaks specifically in terms of human marriage, the relationship between parents and children, and rulers and ruled. This language was widespread in nineteenth and early twentieth-century theology but was controversial in the period between the wars precisely because it was applied to such notions as nation, blood, and race. That is, the idea that there are ‘orders of creation’ was used in support of Nazi ideology, as God-ordained structures of existence that must be supported and maintained.

Although Brunner does not here engage these ideas, the structure of his argument suggests that he is aware of the danger that lurks here and that he repudiates it. Brunner explicitly grounds his doctrine of the ordinances in the divine love; they arise from God’s love for the creature and are given that humanity’s relationships might be ordered by the kind of love that God is and gives. True humanity is not defined by nation, blood, or race but by the image of the God who is love. These other realities divide humans from one another and so by definition fail Brunner’s test of what constitutes authentic human existence.

Finally, Brunner clearly notes that the Decalogue begins with God’s Word of grace but does not draw out the implication that the Decalogue is not so much a ‘republication’ of natural law but commandments for the covenant community. In particular, it is difficult to see how the first table of the law could arise as part of a natural law ethic; these commands are specific for the people of Israel.

There is, therefore, a tension in Brunner’s discussion. The traditional interpretation of Romans 1-2 especially, establishes human culpability before God: we are all sinners and therefore liable to divine wrath and judgement. Brunner maintains this interpretation and strengthens it with his assertion that “in his law God tells us nothing but the natural laws of true human life…” (46). But this diminishes the particularity of the revelation given to Israel and over-estimates the natural knowledge of the divine law that humanity supposedly possesses.

Selection: The Church Dogmatics II/1:25-31, §25.1 “Man before God.”

Selection: The Church Dogmatics II/1:25-31, §25.1 “Man before God.”