Karl Barth approaches this question not as an issue to be explored in and for itself, but as part of his discussion of Jesus Christ as the revelation of God. Specifically, his treatment comes in Church Dogmatics I/2, section 15.2 “The Mystery of Revelation: Very God and Very Man.” Barth’s exposition in this subsection is a meditation on John 1:14 “the Word became flesh,” and in this portion specifically (15.2.ii; pp. 147-159), Barth is considering what is meant when Scripture speaks of the divine word becoming flesh.

Karl Barth approaches this question not as an issue to be explored in and for itself, but as part of his discussion of Jesus Christ as the revelation of God. Specifically, his treatment comes in Church Dogmatics I/2, section 15.2 “The Mystery of Revelation: Very God and Very Man.” Barth’s exposition in this subsection is a meditation on John 1:14 “the Word became flesh,” and in this portion specifically (15.2.ii; pp. 147-159), Barth is considering what is meant when Scripture speaks of the divine word becoming flesh.

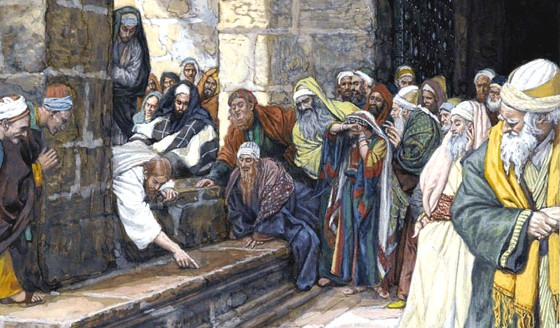

That the Word was made “flesh” means first and generally that He became man, true and real man, participating in the same human essence and existence, the same human nature and form, the same historicity that we have. God’s revelation to us takes place in such a way that everything ascribable to man, his creaturely existence as an individually unique unity of body and soul in the time between birth and death, can now be predicated of God’s eternal Son as well (147).

For Barth, the Johannine phrase means first and primarily that the Word became “participant in human nature and existence”; that is, in the humanitas by which humanity is distinguished as human as opposed to God, angel, or animal (149). Since, however, human “nature” cannot be real in an abstract sense but only in the concrete reality of an actual person, the Word became not simply “flesh” but an existing person, a single individual, the man Jesus Christ. “Thus the reality of Jesus Christ is that God Himself in person is actively present in the flesh. God Himself in person is the Subject of a real human being and acting” (151).

Barth goes further, however, to consider the nature or quality, as it were, of the “flesh” that the Word appropriated:

But what the New Testament calls σάρξ [sarx, “flesh”] includes not only the concept of man in general but also, assuming and including the general concept, the narrower concept of the man who is liable to the judgment and verdict of God, who having become incapable of knowing and loving God must incur the wrath of God, whose existence has become one exposed to death because he has sinned against God. Flesh is the concrete form of human nature marked by Adam’s fall … The Word is not only the eternal Word of God but “flesh” as well, i.e., all that we are and exactly like us even in our opposition to him. It is because of this that He makes contact with us and is accessible for us (151).

Here Barth argues at some length from both Scripture and the history of theology, that the Word became “fallen flesh,” that is, he partook of fallen human nature. “He was not a sinful man. But inwardly and outwardly His situation was that of a sinful man. He did nothing that Adam did. But He lived life in the form it must take on the basis and assumption of Adam’s act” (152). This is precisely what Donald Macleod cannot and will not say. For Barth, though, this is a key distinguishing feature between Christianity and other religions both ancient and modern, which also include instances and concepts of incarnation. In Christian faith, God did not merely become human, and did not come as a hero figure—something found in the other religions, but took the nature identical to ours in the light of the Fall (153).

But this is necessary not simply as an apologetic point. More important is the fact that if the Word has not come to us—actually come all the way to us—then we still reside in the darkness, untouched by the light which has come into the world and which, shining in the darkness, enlightens every person (John 1:5, 9), untouched by revelation and reconciliation. God’s Son has come all the way to us, not only assuming our nature but entering “the concrete form of our nature, under which we stand before God as men damned and lost” (153). Only thus can Christ be “like us” and so represent us before God.

True, the Word assumes our human existence, assumes flesh, i.e., He exists in the state and position, amid the conditions, under the curse and punishment of sinful man. He exists in the place where we are, in all the remoteness not merely of the creature from the creator, but of the sinful creature from the Holy Creator. Otherwise His action would not be a revealing, a reconciling action. He would always be for us an alien word. He would not find us or touch us. For we live in that remoteness. . . . Therefore in our state and condition He does not do what underlies and produces that state and condition, or what we in that state and condition continually do. Our unholy human existence, assume and adopted by the Word of God, is a hallowed and therefore a sinless human existence; in our unholy human existence the eternal Word draws near to us . . . supremely and helpfully near to us (155-156).

Thus although the Word came in sinful flesh, he did not do what we in the flesh do; he committed no sin. Again Barth turns to Scripture, this time to Romans 8:3, to argue that there

In the likeness of flesh (unholy flesh, marked by sin), there happens the unlike, the new and helpful thing, that sin is condemned by not being committed, by being omitted, by full obedience now being found in the very place where otherwise sin necessarily and irresistibly takes place. The meaning of the incarnation is that now in the flesh that is not done which all flesh does (156).

Jesus Christ did not sin, and it was impossible actually that he could for, as we have already noted above, in Christ “God Himself in person is the Subject of a real human being and acting” (151). God is the subject of this genuinely human life, something Barth will go on to explore and exposit in the following paragraphs.

Finally, Barth goes as far as to identify what constitutes Jesus’ sinlessness: standing where we stand in the state and position of fallen humanity Jesus bears the divine wrath which must fall upon sinful humanity.

He judged sin in the flesh by recognising the order of reconciliation, i.e., put in a sinner’s position He bowed to the divine verdict and commended Himself solely to the grace of God. That is His hallowing, His obedience, His sinlessness. Thus it does not consist in an ethical heroism, but precisely in a renunciation of any heroism, including the ethical. He is sinless not in spite of, but just because of His being the friend of publicans and sinners and His dying between the malefactors. . . . This is the revelation of God in Christ. For where man admits his lost state and lives entirely by God’s mercy—which no man did, but only the God-Man Jesus Christ has done—God Himself is manifest (157-158).

Several things are clear in Barth’s exposition. First, he adopts an Alexandrian christology in which the Word assumes human nature, though he goes beyond what the Fathers taught by insisting that it is a fallen human nature. Second, he understands Jesus’ sinlessness as the New Testament portrays it: the fact that Jesus did not sin, rather than in terms of an ontological sinlessness located in sinless flesh. Third, his exposition is shaped by his commitment to the priority of divine grace in salvation, and indeed his exposition serves the proclamation of the gospel of grace, for there is no place here for a Pelagian moral heroism, or for works-righteousness. Rather, the way of Christ as presented by Barth, is the way of salvation for all: a humbling acknowledgement and acceptance of the right of divine justice by which we are condemned as sinners—slain by the word of divine judgement, and yet marvellously and miraculously raised by the mercy of God into the newness of life.

Jesus did not run from the state and situation of fallen humanity, nor seek to bargain with God about the justice or otherwise of his situation, nor sought to improve his situation through his own attempts at moral goodness, but bowed under the divine judgement, and bore it “in solidarity with us to the uttermost,” so that there was done which we do not do: the will of God” (158).

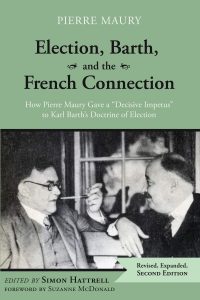

The second edition of Simon Hattrell’s (editor and translator) book on Karl Barth and Pierre Maury is now available from Wipf & Stock. This is an enlarged edition of the book with several additional essays including one by myself entitled “The Light of the Gospel: Election and Proclamation.”

The second edition of Simon Hattrell’s (editor and translator) book on Karl Barth and Pierre Maury is now available from Wipf & Stock. This is an enlarged edition of the book with several additional essays including one by myself entitled “The Light of the Gospel: Election and Proclamation.”

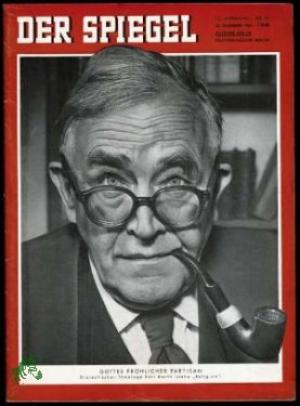

Mark Galli entitles his recent book on Karl Barth an ‘introductory biography for evangelicals.’ As a biography it is a faithful though simplified rendering of the broader and deeper story found in Eberhard Busch’s Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts (1976), upon which it draws heavily. With respect to his intended audience, Galli is writing specifically for evangelical Christians, not as a Barth specialist, but as an appreciative student and fellow-traveller.

Mark Galli entitles his recent book on Karl Barth an ‘introductory biography for evangelicals.’ As a biography it is a faithful though simplified rendering of the broader and deeper story found in Eberhard Busch’s Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts (1976), upon which it draws heavily. With respect to his intended audience, Galli is writing specifically for evangelical Christians, not as a Barth specialist, but as an appreciative student and fellow-traveller.