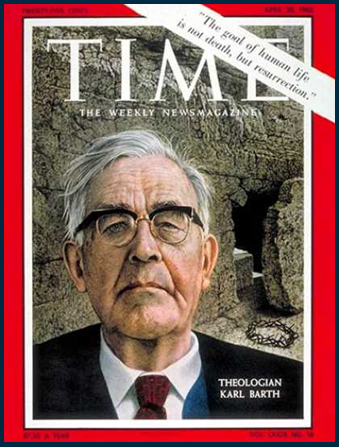

Hunsinger published his excellent article in 1999 with an aim to correct other Barth interpreters who suggest variously, that Barth’s Christology is one-sided, falling into either an Antiochene or Alexandrian mode of expression. Chalcedon, of course, navigated and distinguished the primary concerns of these two ancient christological models. The bishops affirmed the particular truth brought by each model while also steering clear of the problematic aspects of each proposal, Nestorianism in the case of Antioch, and Apollinarianism/Eutychianism in the case of Alexandria. Nevertheless, the council gave greater affirmation to Alexandria, affirming two of its priorities (the divine nature in the single person of Jesus Christ), while affirming only one of Antioch’s priorities (the true human nature of Jesus).

Hunsinger published his excellent article in 1999 with an aim to correct other Barth interpreters who suggest variously, that Barth’s Christology is one-sided, falling into either an Antiochene or Alexandrian mode of expression. Chalcedon, of course, navigated and distinguished the primary concerns of these two ancient christological models. The bishops affirmed the particular truth brought by each model while also steering clear of the problematic aspects of each proposal, Nestorianism in the case of Antioch, and Apollinarianism/Eutychianism in the case of Alexandria. Nevertheless, the council gave greater affirmation to Alexandria, affirming two of its priorities (the divine nature in the single person of Jesus Christ), while affirming only one of Antioch’s priorities (the true human nature of Jesus).

Hunsinger begins by outlining the general features of a Chalcedonian Christology as a “type,” since in his view,

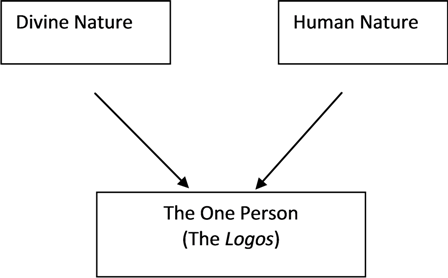

Chalcedonian Christology does not isolate a point on a line that one either occupies or not. It demarcates a region in which there is more than one place to take up residence. The region is defined by certain distinct boundaries. Jesus Christ is understood as “one person in two natures.” The two natures—his deity and his humanity—are seen as internal to his person.[1]

He argues that Barth developed his Christology in Chalcedonian terms, rather than along the lines of simply an Alexandrian or Antiochene model, as has been suggested. He shows that Barth took a dialectical approach to the person of Christ, using now an Alexandrian idiom and now an Antiochene idiom, and insisting that both voices must be heard. Hunsinger defends Barth’s approach by calling upon his readers to attend to Barth’s distinctive method.

Barth is probably the first theologian in the history of Christian doctrine who alternates back and forth, deliberately, between an “Alexandrian” and an “Antiochian” idiom. The proper way to be Chalcedonian in Christology, Barth believed, was to follow the lead of the New Testament itself by employing a definite diversity of idioms. Any other strategy for articulating the Chalcedonian mystery would inevitably have unbalanced or one-sided results.[2]

Barth’s distinctive contribution is to view the work of Christ as at one and the same time both divine and human. In so doing, he managed to be “resoundingly traditional and brilliantly innovative” at the same time.[3] Hunsinger demonstrates Barth’s creative adaption of Chalcedon in three case studies: “First, he actualized the traditional conception of the incarnation. Second, he personalized the saving significance of Christ’s death. Finally, he contemporized the consequences of Christ’s resurrection.”[4]

With respect to the incarnation, for example, Barth views it as a history rather than a state. Jesus Christ acts and does so as a divine and a human act, fully and completely both simultaneously. As such, there is no dividing the activity of Jesus amongst the two natures. In Barth’s hands then, doctrines like the humiliation and the exaltation of Jesus are not read as successive, but as the one act in two aspects:

As he died the death of the sinner, the Son of God entered the nadir of his humiliation for our sakes, even as his exaltation as the Son of man attained its zenith in that sinless obedience which, having freely embraced the cross, would be crowned by eternal life. His humiliation was always the basis of his exaltation, even as his exaltation was always the goal of humiliation, and both were supremely on in his death on our behalf. “It was in this way that the reconciliation of the world with God was accomplished in the unity of his being” (IV/1, 253).[5]

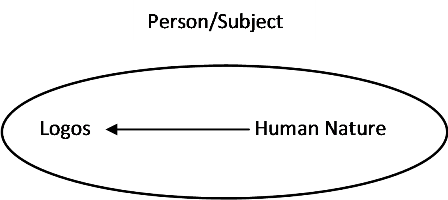

Thus, the inherent dialectic of Christ’s person is at work in the single event of his death: active obedience and exaltation as the Son of man and passive obedience and humiliation as the Son of God, all simultaneously, the work of the one person in the one event. Yet an additional feature of Barth’s dialectic must also be reckoned with:

No symmetry between the two natures that met in Christ was possible. Christ’s deity after all was deity, whereas his humanity was merely humanity. The precedence, initiative, and impartation were always necessarily with his deity even as the subsequence, absolute dependence, and pure if active reception were always necessarily with his humanity (IV/2, 116).[6]

In this way, both the divine will and the human will of Jesus are retained and active, but in a definite and irreversible order. Nevertheless, this “double agency” in the person of Christ is

…not only one of “coordination in difference” (IV/2, 116), but also of one of “mutual participation” for the sake of a common and single work (communicato operationum) (IV/2, 117). When in Christ’s one divine person two natures, and thus also two wills or operations, met, they did so not merely analogically or externally, but in a relation of mutual participation, indwelling or koinonia, and thus in a Chalcedonian unity0in-distinction and distinction-in-unity (IV/1, 126).[7]

*****

[1] Hunsinger, George, “Karl Barth’s Christology: Its Basic Chalcedonian Character,” in Disruptive Grace: Studies in the Theology of Karl Barth, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), 132.

[2] Hunsinger, “Karl Barth’s Christology,” 135.

[3] Hunsinger, “Karl Barth’s Christology,” 141.

[4] Hunsinger, “Karl Barth’s Christology,” 140.

[5] Hunsinger, “Karl Barth’s Christology,” 142.

[6] Hunsinger, “Karl Barth’s Christology,” 146.

[7] Hunsinger, “Karl Barth’s Christology,” 140.