Romans 3:25

Romans 3:25

Whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith. He did this to show his righteousness, because in his divine forbearance he had passed over the sins previously committed (NRSV).

Whom God displayed publicly as a propitiation in His blood through faith. This was to demonstrate His righteousness, because in the forbearance of God He passed over the sins previously committed (NASB).

In his widely-acclaimed commentary on Romans, C. E. B. Cranfield supports the traditional interpretation of this verse which understands Christ’s sacrifice on the cross in terms of a propitiation that averts the divine wrath which would otherwise have been directed against humanity on account of their sin.

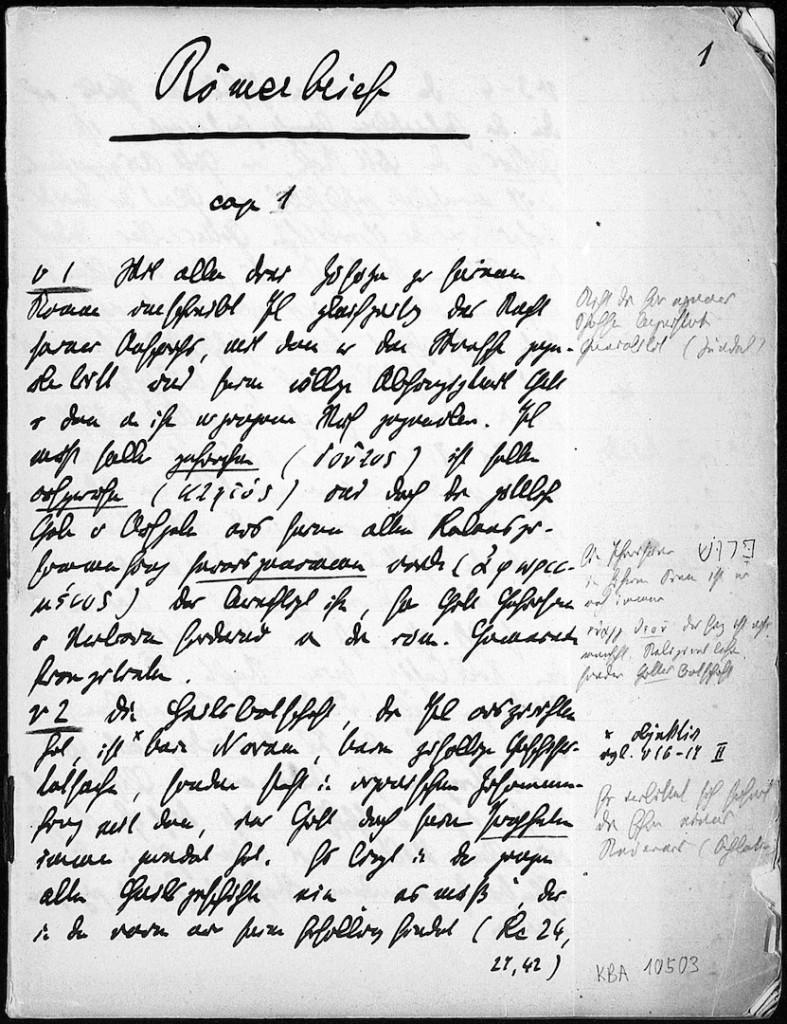

Cranfield begins his exposition of this verse by arguing against the interpretation of the opening phrase of the verse in the two translations cited above. The key phrase is ὃν προέθετο ὁ θεός (hov proetheto ho theos, “Whom God displayed publicly”). Cranfield argues that the verb προέθετο (proetheto) as used in the New Testament can mean either (a) propose to oneself and so to purpose, or (b) to set forth publicly or display. It is clear that the two translations opt for the second of these options whereas Cranfield argues, “There is, in our view, little doubt that ‘purposed’ should be preferred to ‘set forth publicly’” (Cranfield, Romans Vol. 1, I-VIII, International Critical Commentary, 209). It makes better theological sense, suggests Cranfield, to understand Paul’s concern in terms of God’s eternal purpose than as a reference to the Cross as something accomplished in the sight of humanity.

Paul means to emphasize that it is God who is the origin of the redemption which was accomplished in Christ Jesus and also that this redemption has its origin not in some sudden new idea or impulse on God’s part but in His eternal purpose of grace (210).

The second important term in this verse is the word ἱλαστήριον (hilastērion), translated in the NRSV as “sacrifice of atonement” (in a footnote a further option is given: “place of atonement”), and in the NASB as “propitiation.” In the Septuagint (the ancient Greek version of the Old Testament), this word refers twenty-one times to the mercy-seat, that is, the place where the high priest sprinkled the blood of the sin offering on the day of atonement (see Leviticus 16). As such, it is quite possible that Paul is referring to Jesus Christ here, as the place where God effected his saving work. Cranfield, however, demurs. Following Leon Morris, he notes that in the Septuagint references, the noun in all but one case appears with the article when referring to the mercy-seat, whereas in this text it is anarthrous. Further, given Paul’s understanding of the intensely personal and costly nature of Jesus’ sacrifice, Cranfield considers it unlikely that Paul would liken Jesus to a piece of furniture in the temple. Rather, the mercy-seat would more appropriately be a type of the Cross itself, than of Jesus Christ (215). Cranfield, therefore, opts for the term ‘propitiation,’ or more precisely, “a propitiatory sacrifice” (216-217).

Many theologians find this interpretation of hilastērion deeply unsatisfying since it appears to portray God as full of wrath toward humanity, and requiring the blood sacrifice of an innocent victim before he will consider forgiving humanity. The idea that God must be appeased—and that by blood—before he will forgive seems contrary to the God of love revealed in Jesus Christ. Nevertheless Cranfield insists that this is the correct interpretation of this term:

Indeed, the evidence suggests that the idea of the averting of wrath is basic to this word-group in the OT no less than in extra-biblical Greek, the distinctiveness of the OT usage being its recognition that God’s wrath, unlike all human wrath, is perfectly righteous, and therefore free from every trace of irrationality, caprice and vindictiveness, and secondly that in the process of averting this righteous wrath from man it is God Himself who takes the initiative (216).

Further, the decisive factor for Cranfield is that this hilastērion occurs “in his blood” (en tō autou haimati), which indicates that a propitiatory sacrifice is intended.

The purpose of Christ’s being ἱλαστήριον was to achieve a divine forgiveness, which is worthy of God, consonant with his righteousness, in that it does not insult God’s creature man by any suggestion that that is after all of small consequence, which he himself at his most human knows full well (witness, for example, the Greek tragedians) is desperately serious, but, so far from condoning man’s evil, is, since it involves nothing less than God’s bearing the intolerable burden of that evil Himself in the person of His own dear Son, the disclosure of the fullness of God’s hatred of man’s evil at the same time as it is its real and complete forgiveness (214).

We take it that what Paul’s statement that God purposed Christ as a propitiatory victim means is that God, because in His mercy He willed to forgive sinful men and, being truly merciful, willed to forgive them righteously, that is, without in any way condoning their sin, purposed to direct against His own very Self in the person of His Son the full weight of that righteous wrath which they deserved (217).

In his treatment of this text Cranfield hits exactly the right notes. He acknowledges the reality of divine wrath as the overarching backdrop against which the saving work of Christ occurs. He insists that God’s wrath is righteous, and as such is entirely different to human wrath. That this wrath is occasioned by human wickedness indicates the seriousness with which God views this wickedness, displays the righteousness of God’s character in his response to sin, and affirms the genuine significance of human value, decision and act. Most importantly, he shows that God’s eternal purpose toward humanity was and is mercy, not wrath, and that God has determined to direct against himself—in the person of his Son—the wrath occasioned by human sin, in order to be merciful toward humanity and righteous in his mercy. This opens up a crucial window of understanding with respect to this verse and the atonement in general: it must be understood in trinitarian terms.

Finally, and with an eye on the topic I am exploring in this short series of posts, Cranfield is correct to insist that this hilastērion is “in his blood.” “It was by means of the shedding of His blood that, according to the divine purpose, Christ was to be ἱλαστήριον. … A sacrificial significance attaches to the use of the word αἷμα [‘blood’]. … There is little doubt that this is so in the verse under consideration” (210-211). The “blood of his cross” was the sacrificial means by which God has shown mercy to us while maintaining his unimpeachable righteousness.

In his widely-acclaimed commentary on Romans, C. E. B. Cranfield says of Barth’s commentary,

In his widely-acclaimed commentary on Romans, C. E. B. Cranfield says of Barth’s commentary,

One of the features of Barth’s mind and work concerns the relentless nature of his questions by which he penetrates his topic, lays open its inner dynamic, and presses his criticism. Barth probes and interrogates his conversation partners by means of his questions. An example is seen in Church Dogmatics II/2:63-64. Barth has shown that the Reformers and their heirs want to look to Jesus as the ground of their assurance with respect to divine election. Strong statements are found in the tradition, by Luther, Melanchthon, Calvin, Bullinger, the Helvetic Confession, the Formula of Concord, and so on. Nevertheless Barth subjects the tradition to a dozen probing questions, although ultimately, they are all variations of the one central question:

One of the features of Barth’s mind and work concerns the relentless nature of his questions by which he penetrates his topic, lays open its inner dynamic, and presses his criticism. Barth probes and interrogates his conversation partners by means of his questions. An example is seen in Church Dogmatics II/2:63-64. Barth has shown that the Reformers and their heirs want to look to Jesus as the ground of their assurance with respect to divine election. Strong statements are found in the tradition, by Luther, Melanchthon, Calvin, Bullinger, the Helvetic Confession, the Formula of Concord, and so on. Nevertheless Barth subjects the tradition to a dozen probing questions, although ultimately, they are all variations of the one central question: