Romans 3:25

Romans 3:25

Whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith. He did this to show his righteousness, because in his divine forbearance he had passed over the sins previously committed (NRSV).

In his discussion of Romans 3:25 Douglas Moo, like C.E.B. Cranfield, also supports a traditional understanding of the text, including the idea of propitiation as a decisive turning aside of divine wrath. In fact, Moo argues that, “the conclusion that hilastērion includes reference to the turning away of God’s wrath is inescapable” (Moo, The Epistle to the Romans NICNT, 235).

Moo bases this conclusion on two primary arguments. First, the linguistic evidence is clear that the word group in common Greek usage undoubtedly meant the “means of propitiation,” referring, of course, to pagan practices which sought to appease otherwise hostile gods. Of course Moo rejects the idea that propitiation in Paul’s thought was in any way the same as that practised in the pagan contexts: God’s wrath is neither vindictive nor capricious but just, and further, it is God who is the subject of this propitiation, not sinful humans seeking to assuage the wrath of an offended deity (235-236). Moo contends that it was precisely this common meaning, however, that the editors of the Septuagint had in mind when they appropriated the term in their translation of the Hebrew Scriptures:

Dodd is almost certainly wrong on this point. The OT frequently connects the ‘covering,’ or forgiving, of sins with the removal of God’s wrath. It is precisely the basic connotation of ‘propitiate’ that led the translators of the LXX to use the hilask– words for the Hebrew words denoting the covering of sins. This is not, however, to deny the connotation ‘expiation’; the OT cult serves to ‘wipe away’ the guilt of sin at the same time as—and indeed, because—the wrath of God is being stayed (235).

Second, Moo appeals to the context of Romans, especially chapters 1-3 where the wrath of God is an overarching theme. Together, these strands of evidence support the idea that propitiation is as least part of what Paul intended when he used the term hilastērion.

It is also apparent that Moo is not arguing that this is the sole connotation of Paul’s use of the term. Moo acknowledges that the translation of hilastērion as ‘mercy-seat,’ and so as the place where atonement is effected,

Has an ancient and respectable heritage [and] has been gaining strength in recent years. It is attractive because it gives to hilastērion a meaning that is derived from its ‘customary’ biblical usage, and creates an analogy between a central OT ritual and Christ’s death that is both theologically sound and hermeneutically striking (233).

Moo is satisfied to accept this translation so long as the term ‘mercy-seat’ is understood in a semi-technical way as referring to the atonement as a whole. Allowing this perspective meets Cranfield’s objection that the mercy-seat could be analogous only to the cross rather than to Jesus himself.

Turning his attention to the phrase “in his blood” (en tō autou haimati), Moo notes that the blood of Jesus is the means by which God’s wrath is propitiated, though the term itself is expressive of Jesus’ death as a sacrifice. Here, again, we are confronted with the question as to whether God required a payment, a blood-price, the sacrifice of an innocent victim, before he could or would extend forgiveness. Like Cranfield, Moo turns in a trinitarian direction to address this objection to his interpretation of this key text:

While the persons of God the Father and God the Son must be kept distinct as we consider the process of redemption, it is a serious error to sever the two with respect to the will for redemption, as if the loving Christ had to take the initiative in placating the angry Father. God’s love and wrath meet in the atonement, and neither can be denied or compromised if the full meaning of that event is to be properly appreciated. ‘Our own justification before God rests on the solid reality that the fulfilling of God’s justice in Christ was at the same time the fulfilling of this love for us’ (230-231; Moo cites Philip E. Hughes, The True Image, 360).

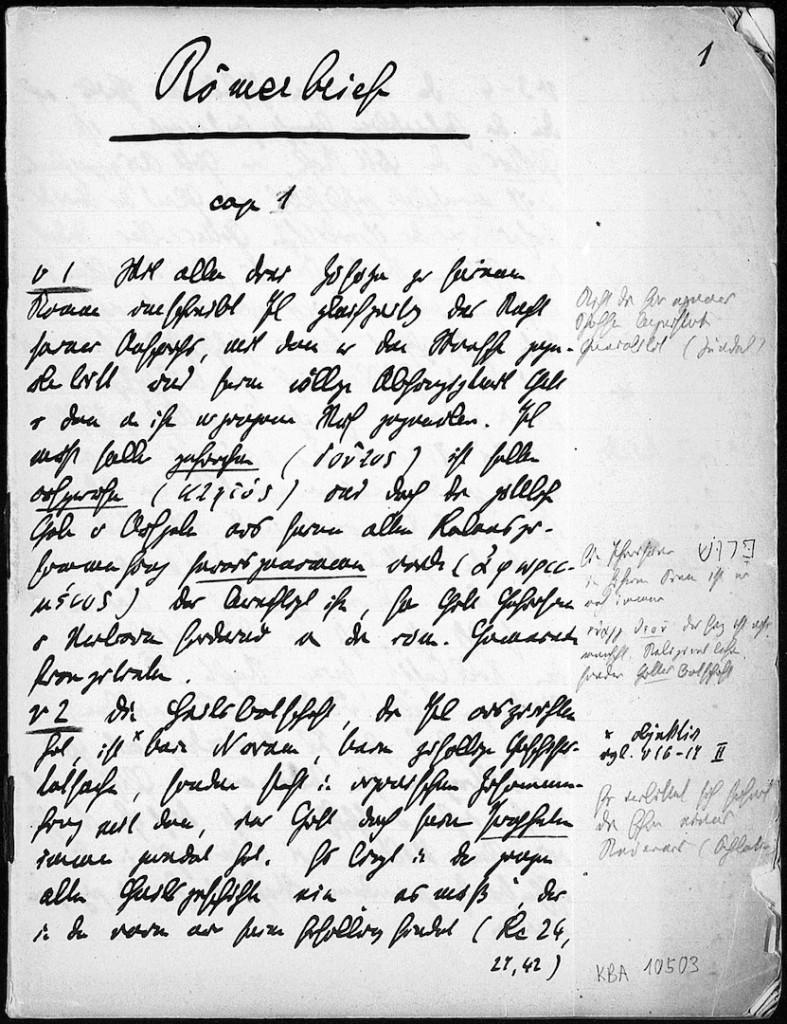

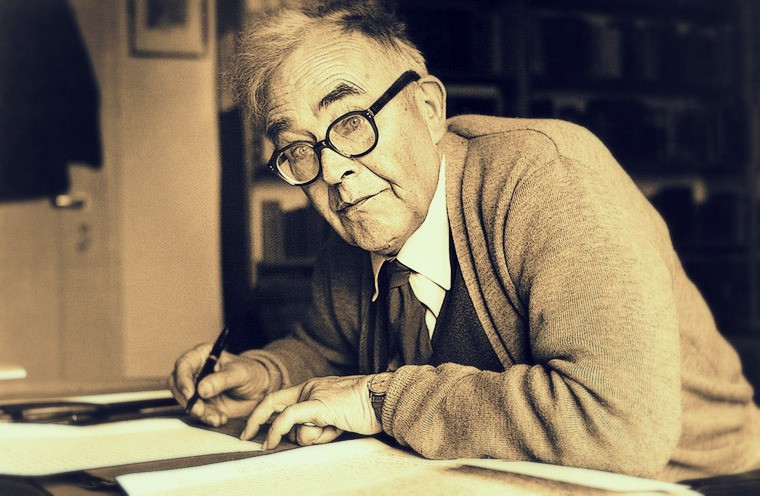

One of the features of Barth’s mind and work concerns the relentless nature of his questions by which he penetrates his topic, lays open its inner dynamic, and presses his criticism. Barth probes and interrogates his conversation partners by means of his questions. An example is seen in Church Dogmatics II/2:63-64. Barth has shown that the Reformers and their heirs want to look to Jesus as the ground of their assurance with respect to divine election. Strong statements are found in the tradition, by Luther, Melanchthon, Calvin, Bullinger, the Helvetic Confession, the Formula of Concord, and so on. Nevertheless Barth subjects the tradition to a dozen probing questions, although ultimately, they are all variations of the one central question:

One of the features of Barth’s mind and work concerns the relentless nature of his questions by which he penetrates his topic, lays open its inner dynamic, and presses his criticism. Barth probes and interrogates his conversation partners by means of his questions. An example is seen in Church Dogmatics II/2:63-64. Barth has shown that the Reformers and their heirs want to look to Jesus as the ground of their assurance with respect to divine election. Strong statements are found in the tradition, by Luther, Melanchthon, Calvin, Bullinger, the Helvetic Confession, the Formula of Concord, and so on. Nevertheless Barth subjects the tradition to a dozen probing questions, although ultimately, they are all variations of the one central question: