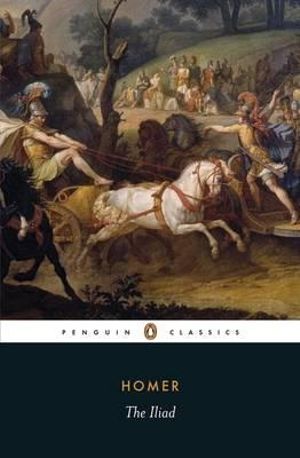

Homer, The Iliad Penguin Classics (London: Penguin, 1987), lv + 460pp. ISBN:978-0-14-044444-5.

Finally I have taken down this epic of Western culture and literature, after its having sat waiting on my shelf for many years, and read it. What a tragic and yet noble story it is, full of human characters (and gods), some appearing fleetingly only to die, others who live on to tell the tale of what must surely be understood—in our day at least—as a tragic tale of wasted years and lives. The opening sentence of the story sets the context of the whole:

Finally I have taken down this epic of Western culture and literature, after its having sat waiting on my shelf for many years, and read it. What a tragic and yet noble story it is, full of human characters (and gods), some appearing fleetingly only to die, others who live on to tell the tale of what must surely be understood—in our day at least—as a tragic tale of wasted years and lives. The opening sentence of the story sets the context of the whole:

Sing, goddess, of the anger of Achilleus, son of Peleus, the accursed anger which brought uncounted anguish on the Achaians and hurled down to Hades many mighty souls of heroes, making their bodies the prey to dogs and the birds’ feasting: and this was the working of Zeus’ will.

This is a tale of unrelenting human pride and anger which sets in train a great conflict. And yet, as the opening sentence signifies, even the will of mighty Achilleus is not determinative, for over against human will stands the unremitting and all-powerful will of Zeus.

What did I notice as I read this classic story?

First, it is a man’s world. Women feature in the story only as wives and mothers bound to the domestic sphere, although they may also appear as captives and as ‘prizes.’ Men act in public, in war and battle, and for glory. This action is often violent, and in the quest for supremacy, free rein is given for the expression of anger, revenge, etc.

Second, the definitive social ethos within which the narrative moves, is that of honour and shame. Honour is earned, especially in battle, but honour also exists by virtue of rank in a hierarchical society, and for the aged, so long as it is an honour accrued earlier in life.

Third, life ends in Hades or the grave. Thus the pursuit of one’s honour is entirely focussed on this world. All one’s hopes are here—for the accumulation of honour, a life well-lived, home and family, and so on.

Fourth, the gods are many, aloof, and yet also engaged in human affairs. They are somewhat capricious, and at war amongst themselves. They intervene in human affairs though human decision and agency is also significant though circumscribed. Nonetheless, fate rules human life even more than the gods. Each person’s fate is woven at birth, and so a sense of inevitability pervades life and undermines agency.

This is a portrayal of gods and humanity in which the former is made in the image of the latter, and for all its talk of honour, human life is brutal, fated, and tragic. How very different from the biblical-Hebraic vision of humanity made in the image of God and endowed with dignity, stewardship, responsibility, and hope!

The descriptive power of the book with its catalogue of recurring images, vivid metaphors, heroic characters, and endless adjectives remind one that it was likely written in order to be read aloud and performed. Even in the twenty-first century The Iliad remains a powerful story, and worth reading on account of its imagery, the rich characterisation and evocation of both the dignity and the depravity of humankind, the condensing of all of this life into four long days of drama, triumph, and anguish, and for its innate historical interest and civilizational impact. As Martin Hammond (translator) asserts in the introduction: “The Iliad is the first substantial work of European literature, and has fair claim to be the greatest.”

And now, sometime soon hopefully, the Odyssey and the Aeneid.