Selection: The Church Dogmatics II/2:25-34, The Orientation of the Doctrine of Election.

Selection: The Church Dogmatics II/2:25-34, The Orientation of the Doctrine of Election.

Barth concludes his discussion of the orientation of the doctrine by viewing his three central characteristics through the lens of the gospel. The election of God is not bare choice as though the concept of choice can be absolutized.

If we are to understand and explain the nature of this primal and basic act of God, we cannot stop, then, at the formal characteristic that it is a choice. We must resist the temptation to absolutise in some degree the concept of choosing or electing. … It cannot well be denied that there has taken place such an absolutizing of the concept of electing, or of its freedom, with the accompanying influence of a non-Christian conception of God, in the history of the doctrine. … As against that, we must take as our starting-point the fact that this divine choice or election is the decision of the divine will which was fulfilled in Jesus Christ, and which had as its goal the sending of the Son of God (25).

The freedom of God’s decision is not an abstract freedom, but the freedom of the God who loves in freedom. God’s love is the movement toward fellowship, ultimately expressed in John 3:16. Election can be understood only in these terms, and therefore, only as gospel. “What takes place in this election is always that God is for us; for us, and therefore for the world which was created by Him, which is distinct from Him, but which is yet maintained by Him. … This much is certain, that in this election…God loved the world. (25-26).

Barth acknowledges that God’s love toward the world may be resisted and opposed and that there remains a “definite sphere of damnation ordained and determined by God as the negation of the divine affirmation…but the divine affirmation, the divine willing as such, is salvation and not damnation. The message of God’s election means always the message of the Yes determined and pronounced by God” (27). Even in hell we can think only of the love of God; we may have refused God’s election but God has not refused us. “In that decree as such we find only the decree of His love. In the proclaiming and teaching of His election we can hear only the proclaiming of the Gospel” (27).

Thus with respect to the three aspects of a serious doctrine of election, Barth insists,

1. That the freedom of God’s grace and decision unconditionally precedes the creature and so is the ground of the “final and severest humiliation of the creature” (28). God is free to say Yes and, Nevertheless, in the face of human opposition, and so free also to forgive our sins and overcome our resistance to him (31). God’s Yes is his final word and ultimate intent, and is the word which we must declare. The human No is vanquished in the divine Yes; i.e. it cannot be ultimate. Neither, however, can the creature despair. It is humiliated, decentred and relocated, not in autonomy but in the overarching sphere of divine grace. Does this mean human decision is not real? No, but it does mean that it is not ultimate.

He is free rather, and His hand is almighty, in the fact that He can rescue the creature from the destruction into which it has plunged itself by its opposition. He is free in the fact that He can turn it in spite of itself to the salvation and life which are the positive and distinctive meaning and goal of His love. And it is that which God elects (28-29).

2. That the mystery of election remains: it is grounded in God’s own good pleasure which knows no “Wherefore”, that is, no cause outside of God’s own good will. Because it remains inexplicable to us, we can but bow before the gracious God and submit ourselves to him.

Confronted with the mystery of God, the creature must be silent: not merely for the sake of being silent, but for the sake of hearing. Only to the extent that it attains to silence, can it attain to hearing. But, again, it must be silent not merely for the sake of hearing, but for that of obeying. For obedience is the purpose and goal of hearing. Our return to obedience is indeed the aim of free grace. It is for this that it makes us free. … In its very character as unseaerchable the election of God demands as such our obedience. It is not proclaimed to us, nor does it reach us…if in and with that election there is no summons to obedience—quite irrespective of the accusation laid against us, the curse resting upon us, the death showing our whole life. From these very things the election of grace has, in fact, released us (30).

Whereas, therefore, in God’s freedom human decision is relativised, in God’s mystery it is required. Election calls for obedience and worship, silence and hearing. Yet obedience is not self-effort, merit or even confirmation of our election. It is acknowledgement; that is, the believer is called to an obedience already fulfilled, and therefore this call is gospel, a call to peace. God’s yes to the creature is total and eternal; God has claimed the creature as his own, and thus claimed, “it has no longer any need to justify itself, to defend itself, or to save itself. It may be silent and still before this mystery” (32).

3. That the divine righteousness of God both judges and saves us. God is vindicated by his righteousness in judging us, yet God’s righteousness is the faithfulness he expresses to the creature in mercy and forgiveness. God’s righteousness is viewed as God being true to God’s own self and purpose. His righteousness means that,

God does not acquiesce in the creature’s self-destruction as its own enemy. He sees to it that His own prior claim on the creature, and its own true claim to life is not rendered null and void. He cares for the creature as for His own possession. And in seeking its highest good, He magnifies his own glory. We cannot distinguish God’s kingly righteousness from his mercy (34).

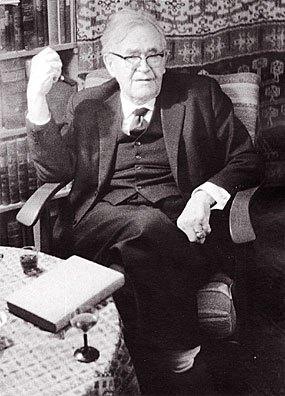

The other day one of my students asked me, “In one sentence, why do you like Karl Barth?” There are probably many answers to that question but what came out of my mouth was, “When I read Barth, I find the gospel comes alive for me.”

The other day one of my students asked me, “In one sentence, why do you like Karl Barth?” There are probably many answers to that question but what came out of my mouth was, “When I read Barth, I find the gospel comes alive for me.”