Just yesterday another question popped up on Facebook and again I have attempted to answer it, however inadequately. I should note that this is a very good question but also one with very demanding implications. There are actually two questions and I am aware that I have not addressed the second question specifically, but I think my answer to the first will provide indications of how I might address that second answer. As it happens, I am also in the midst of marking a series of graduate essays on precisely this question: “What is systematic theology, and what use is it?” Some of the essays have been excellent, and I may ask a student if I may reproduce their essay here. In the meanwhile, here is the question posed and my answer:

Just yesterday another question popped up on Facebook and again I have attempted to answer it, however inadequately. I should note that this is a very good question but also one with very demanding implications. There are actually two questions and I am aware that I have not addressed the second question specifically, but I think my answer to the first will provide indications of how I might address that second answer. As it happens, I am also in the midst of marking a series of graduate essays on precisely this question: “What is systematic theology, and what use is it?” Some of the essays have been excellent, and I may ask a student if I may reproduce their essay here. In the meanwhile, here is the question posed and my answer:

Christians have been discussing theology for nearly 2000 years. If systematic theology is “faith seeking understanding” then what understanding has been revealed through all the discussions (in all the seminaries, in all the towns, in all the world)? What do we understand now that we didn’t understand when Jesus completed his earthly ministry?

Ah, dear friend, you need not have worried that your question would in some way offend me – I love it when students ask questions! Still let me address your question, though I suspect as you will note, that you already know the answer!

The irony of your question is that you are doing theology in the asking of it. What relation does a man who lived two millennia ago have to do with us today? What is his significance? On what grounds is that significance based? Why is this Jesus not lost in the mists of history as were so many of his contemporaries? Why should anyone today pay the slightest attention to him? The answer to any and all of these questions involves the doing of theology. This, of course, must be done afresh in every generation.

There are likely many ways of approaching this task, but a time-tested and proven way is to approach the task historically. This works well for several reasons, not least of which is that we are all very unoriginal and manage to come up with the same problems, questions and errors that have been raised time and again in the history of the tradition. The tradition gives us exemplary answers to some questions; shows the limits of our ability with respect to other questions, indicates exemplary and less-than-exemplary methods in approaching these questions, highlights the fact that the very questions we ask are often contingent on our own place in history, and shows us many, many bypaths that are best avoided. For example, the innocent idea (delusion?) that one can simply read the Bible for oneself and come up with the unsullied truth.

One can, of course, simply read the Bible and come up with faith, and this too is a wonderful thing. But even that faith will generate a range of questions that will then be answered with a host of better and worse answers. And so theology begins…

Further, virtually everything we know of this Jesus comes from a very small collection of a ancient sources, written in ancient languages, in ancient contexts so very different from our own. Thus all kinds of hermeneutical issues are raised – afresh in every generation. Get two people reading the same biblical text and you will end up with two – or likely more – possible interpretations of what the text means and what its significance is and what the range of its applications might entail. Thus theology is inevitable, again, as a fresh work in every generation…

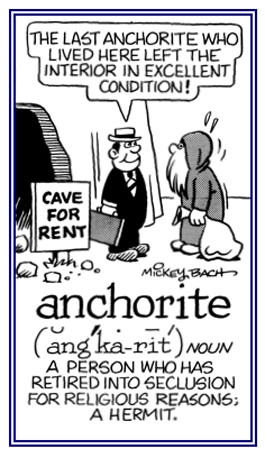

But you know this already – I suspect it is the implications of it you avoid. But, alas, you cannot and will not avoid them even if you take the life of an anchorite. Or you could become a fundamentalist of one kind or another…that always remains an option!