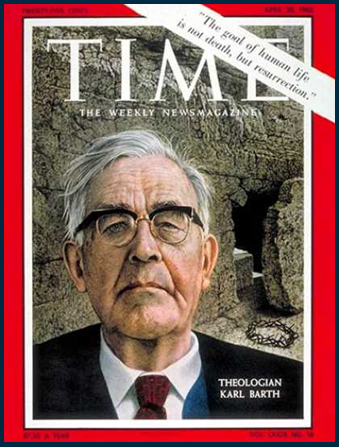

Selection: The Church Dogmatics II/2:34-44, The Foundation of the Doctrine.

Selection: The Church Dogmatics II/2:34-44, The Foundation of the Doctrine.

In the second sub-section of Barth’s prologue to the doctrine of election, he considers the source and foundation of the doctrine. He begins by identifying four insufficient bases for the doctrine including simple repetition of the tradition, the utility or usefulness of the doctrine, Christian experience, and a focus on the omnipotent divine will. Of these, Barth focuses especially on the third and fourth items which although wrong in form (52), are yet somewhat correct in intent or substance, in that they at least direct their attention to the elect person and the electing God. Barth declares his methodological hand early:

We must at this point recall the basic rule of all Church dogmatics: that no single item of Christian doctrine is legitimately grounded, or rightly developed or expounded, unless it can of itself be understood and explained as a part of the responsibility laid upon the hearing and teaching Church towards the self-revelation of God attested in Holy Scripture. Thus the doctrine of election cannot legitimately be understood or represented except in the form of an exposition of what God Himself has said and still says concerning Himself. It cannot and must not look to anything but the Word of God, nor set before it anything but the truth and reality of that Word (35).

Barth does not reject tradition, of course, but insists that it cannot be the subject and norm of dogmatic effort. Rather its function is to serve the Word.

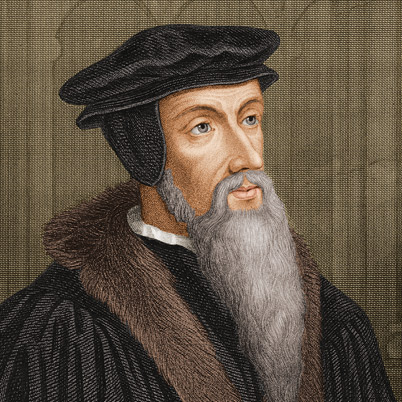

But we shall be doing Calvin the most fitting honour if we go the way that he went and start where he started. And according to his own most earnest protestations, he did not start with himself, nor with his system, but with Holy Scripture as interpreted in his system. It is to Scripture that we must again address ourselves, not refusing to learn from that system, but never as ‘Calvinists without reserve.’ And it is to Scripture alone that we must ultimately be responsible (36).

In turning to Scripture, however, care must be exercised lest Scripture be misused:

Is it right to go to the Bible with a question dictated to us by experience, i.e., with a presupposition which has only an empirical basis, in order then to understand the statements of the Bible as an answer to this question, which means chiefly as a confirmation of the presupposition which underlies the question? … If it is to be a question of the divine judgment, as it must be in dealing with the doctrine of election, then Scripture must not be brought in simply as an interpretation of the facts of the case as given by our own judgment. The very facts which we consider must be sought not in the realm of our experience but in Scripture, or rather in the self-revelation of God attested in Scripture (38).

Barth insists that the doctrine of election cannot be read off our experience of the results of gospel proclamation and human response. Such an approach not only is a misuse of Scripture but presumes that the judgement of human experience is equivalent with divine judgement. Barth’s discussion in this matter, then, is a decisive repudiation of Calvin’s approach (39-41), whom he accuses of feeling very competent to distinguish “if not the reprobate, at least the stupid and deceived and wicked who in that age formed so distressingly large a majority of men” (40).

The fact which above all others inspired Calvin, and was thus decisive for the formation of his doctrine, was not at all the contrast between the Church on the one hand, and on the other the heathen world entirely unreached by the Gospel. … Again, it was not the positive observation that at all times the Gospel has both reached so many externally and also seemed to prevail over them internally. … [but] that other fact of experience which excites both pain and anger, the fact of the opposition, the indifference, the hypocrisy and the self-deception with which the Word of God is received by so many of those who hear it (80 per cent, according to the estimate there given). And it is this limiting experience, the negative in conjunction with the positive, which is obviously the decisive factor as Calvin thought he must see it. It was out of this presupposition, laid down with axiomatic certainty, that there arose for him the magnae et arduae quaestiones [great and difficult questions] for which he saw an answer in what he found to be the teaching of Scripture (39-40).

Behind this approach is a presupposition that election concerns God’s eternal and decisive foreordination of every individual in their private relation to God, which is then understood, on the basis of experience, in terms of election and rejection. Although Barth accepts that every person does indeed stand in a private and individual relation to God, and that this relation is indeed decisively determined by God’s election, he nevertheless rejects the presupposition that election is focussed first and primarily on the individual, and the corollary idea that each individual’s private relation to God is thereby unalterably established and determined in advance. God’s election is gracious and free, focussed specifically and primarily on Jesus Christ and his people, and only then on the individual (41-44). The great danger, Barth suggests, is that reading divine election from our experience of the fruitfulness or otherwise of the proclamation of the gospel will result in a portrayal of the electing God who resembles “far too closely the electing, and more particularly the rejecting theologian”! (41)