Erickson’s three chapters on the Holy Spirit are not the strongest section of his work. Nevertheless, in his chapter on the person of the Holy Spirit, he argues effectively on the basis of indirect biblical testimony that the Holy Spirit is a divine personality, at once fully God and fully personal. This is crucial, for the Spirit is the God who in a supremely personal and intimate way, is God with us. “The Holy Spirit is a person, not a force, and that person is God, just as fully and in the same way as are the Father and the Son” (786).

Erickson’s three chapters on the Holy Spirit are not the strongest section of his work. Nevertheless, in his chapter on the person of the Holy Spirit, he argues effectively on the basis of indirect biblical testimony that the Holy Spirit is a divine personality, at once fully God and fully personal. This is crucial, for the Spirit is the God who in a supremely personal and intimate way, is God with us. “The Holy Spirit is a person, not a force, and that person is God, just as fully and in the same way as are the Father and the Son” (786).

The deity of the Holy Spirit is not as easily established as is the deity of the Father and the Son. It might well be said that the deity of the Father is simply assumed in Scripture, that of the Son is affirmed and argued, whole that of the Holy Spirit must be inferred from various indirect statements found in Scripture (782).

Erickson helpfully provides a thumbnail sketch of the development of the doctrine of the Holy Spirit in the history of theology, moving quickly through the pre-Nicene period to the controversies which resulted in the creedal affirmation of the Spirit’s deity at Constantinople. He notes in passing issues such as the Montanists and the Filioque, treats minimally developments in the medieval and Reformation periods and notes the long period of decline with respect to the doctrine in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, “due to a variety of movements, each of which in its own way regarded the Spirit and his work as either superfluous or incredible.” I note with interest his fascinating comment with respect to the first of these movements:

One of those movements was Protestant scholasticism. It was found in Lutheranism, and particularly the branch that derived its inspiration from the writings of Philipp Melanchthon. As a series of doctrinal disputes took place, it became necessary to define and refine beliefs more specifically. Consequently, faith came increasingly to be thought of as rechte Lehre (correct doctrine). A more mechanical view of the role of the Scriptures was developed, and, as a result, the witness of the Spirit tended to be bypassed. Now a Word alone, without the Spirit, was regarded as the basis of authority. Since belief rather than experience came to be viewed as the essence of the Christian religion, the Holy Spirit was increasingly neglected (779).

This problem, unfortunately, persists today—see my post on Paul Helm’s treatment of Calvin’s inner testimony of the Spirit. There are many today who want to establish the authority of Scripture not simply on a doctrine of Scripture, but on an authorised interpretation of Scripture that also presupposes an implicit hermeneutic and application. Erickson is correct to insist that Christian faith cannot be reduced to correct doctrinal belief. This is not to say, of course, that doctrine is unimportant; Erickson would be the first to reject such a view. Good doctrine helps ground, secure and explain our faith intellectually. It protects us in the face of the variety of experiences which we and others have. Nonetheless, this experiential aspect of Christian faith, this reception of the Spirit, is crucial. “Let me ask you this only: did you receive the Spirit by works of the law or by hearing with faith?” (Galatians 3:2).

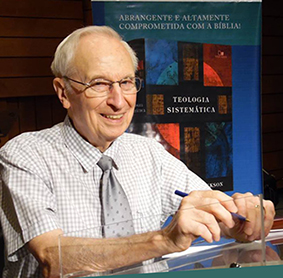

I trust Professor Doktor Millard Erickson. He is one of the best Christian theologians !

Thanks, Mariana! Yes, Erickson is a reliable and informed evangelical theologian, well worth reading. Thank you for visiting.

I totally agree. Millard Erickson is a great theologian. He gives great insight in Scriptural doctrines.