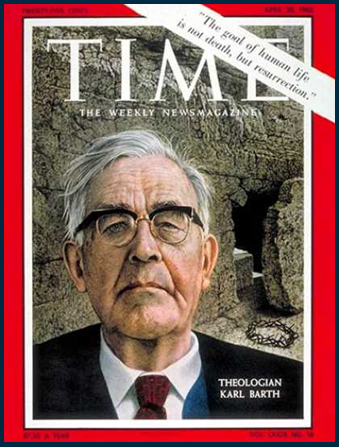

Bruce McCormack is not content simply to refer to Barth’s Christology as Chalcedonian, contra George Hunsinger. McCormack acknowledges that Barth has retained the “values” of Chalcedon (i.e. “two natures in one person”), but argues that Barth has fundamentally reworked what this means by developing his Christology on entirely different grounds to that of Chalcedon. He argues that Barth’s Christology developed over the course of his career, even within the period of the Church Dogmatics. In volume I/2 his Christology is largely Chalcedonian, but by volume IV/1-3, Barth had reworked his ontology in light of his doctrine of election, with the result that there are now fundamental differences between his Christology and that of Chalcedon, and yet without compromising the fundamental achievement of Chalcedon. McCormack develops his thesis as follows.

Bruce McCormack is not content simply to refer to Barth’s Christology as Chalcedonian, contra George Hunsinger. McCormack acknowledges that Barth has retained the “values” of Chalcedon (i.e. “two natures in one person”), but argues that Barth has fundamentally reworked what this means by developing his Christology on entirely different grounds to that of Chalcedon. He argues that Barth’s Christology developed over the course of his career, even within the period of the Church Dogmatics. In volume I/2 his Christology is largely Chalcedonian, but by volume IV/1-3, Barth had reworked his ontology in light of his doctrine of election, with the result that there are now fundamental differences between his Christology and that of Chalcedon, and yet without compromising the fundamental achievement of Chalcedon. McCormack develops his thesis as follows.

Barth rejected the underlying substantialist ontology of Chalcedon in order to preserve the immutability of God in the human life of Jesus. That is, the incarnation and crucifixion of Jesus do not constitute “change” in the divine being, for God can become human and as human even die without ceasing to be God, because God has eternally self-determined to be God only in this way. Jesus Christ, in his divine-human unity has taken death into the divine life, but has not been conquered by it.[1] This “death in God” does not change God because Barth does not conceive of God’s being in terms of substance but in terms of act. McCormack defines his terms as follows:

The language of “essence” is certainly innocent enough. It refers merely to the thought of a self-identical element that perdures through all the changes that take place in a person/thing through time. It is that which makes a person/thing to be what it is, all other qualities being understood as nonessential. The Greek category of “substance” (in all of its various forms) makes the self-identical element in “persons” (which is our interest here) to be complete in itself apart from, and prior to the decisions, acts and relations by means of which the life of the person in question is constituted. “Substance,” then, is a timeless idea; a concept whose content is complete in abstraction from an individual’s lived history.[2]

For McCormack, if God is conceived in terms of an eternal and underlying substance, the incarnation must mean a change in what God is. Further,

If the definition of “immutability” is controlled by a notion of “substance” in the way described, then it becomes impossible to understand the human nature of Jesus Christ as the human nature of the eternal Logos. Any attribution of human qualities or activities of experiences to the Logos would set aside the “immutability” of the Logos. … The unity of the Logos and his human nature can only be achieved through the abandonment of substantialist thinking and the “abstract” theological epistemology that makes it possible.[3]

For McCormack—following Barth—not only is God known through what he does, God is what he does. We learn what God is and does not through philosophical speculation, but by attentively “following after” God’s movement into history in all its concreteness.[4] That is, Barth asks concerning the constitution of God in eternity given what God has done in time. This divine doing has its ground in the first divine act of election in which God determined to be God in this way and not otherwise. That is, God determined to be God-for-us in the covenant of grace, in uniting humanity into his own being in the person of the Logos.

To God’s being-in-act in eternity there corresponds a being-in-act in time; the two are identical in content (or, as we might also say, the “immanent Trinity” and the “economic Trinity” are identical in content). Clearly, immutability has been preserved here. But it has been newly defined.[5]

[1] McCormack, Bruce L., “The Ontological Presuppositions of Barth’s Doctrine of Atonement,” in The Glory of the Atonement: Biblical, Theological & Practical Perspectives, ed. Hill, Charles E. & Frank A. James, (Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press, 2004), 361.

[2] McCormack, “Ontological Presuppositions,” 357, original emphasis.

[3] McCormack, “Ontological Presuppositions,” 357.

[4] McCormack, “Ontological Presuppositions,” 358.

[5] McCormack, “Ontological Presuppositions,” 359.