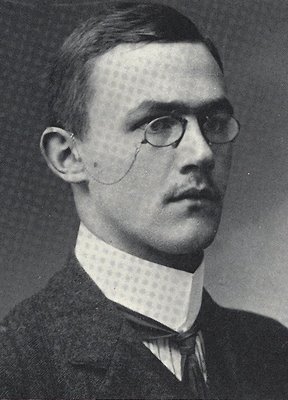

Selection: The Church Dogmatics IV/4:31-40, Baptism with the Holy Spirit.

Selection: The Church Dogmatics IV/4:31-40, Baptism with the Holy Spirit.

Karl Barth brings his meditation on “Baptism with the Holy Spirit” to a conclusion with a summation in five points of what he means by this term, including a discussion of the form of Christian life which issues from this work of God, as is appropriate in a discussion of ‘the command of God the Reconciler.’

First, Barth reiterates that the beginning of Christian life is the ‘direct self-attestation and self-impartation of the living Jesus Christ’ in the work of the Holy Spirit. He alone is the author and finisher of Christian faith. Jesus Christ himself is the divine change which occurs in a person’s life and by which they become a Christian. Barth’s emphasis here is to preclude the idea that the Christian life results on account of the mediation of the Christian community, or even the Scripture. Jesus Christ may use these means as an instrument of his Word, but his call to a person is direct and immediate. This is a person’s Baptism with the Holy Spirit, whereby Jesus Christ imparts ‘Himself as at once the Guarantor of God’s faithfulness to him and of his own faithfulness to God’ (33).

Second, this divine work whereby Jesus Christ gives himself to specific persons in the work of the Holy is the form of grace in which God actually reconciles the world to himself. ‘Baptism with the Holy Spirit is effective, causative, even creative action on man and in man. It is, indeed, divinely effective, divinely causative, divinely creative’ (34). That is, it is not the human response or the ecclesial work of water baptism which is the means of this grace, but the direct work of Jesus Christ as he baptises with the Holy Spirit. By this grace a person is changed ‘truly and totally,’ and is liberated for their own decision of faithfulness in correspondence to the faithfulness shown them by God. This divine change is so transformative the person can and will never forget it (35).

Third, this ‘omnipotently penetrating and endowing’ grace demands the response of gratitude, for this grace not only liberates the person for a new obedience but claims them for this obedience to their new Lord and Master whom they have now acquired. The grace that forgives and frees also commands (35).

The problem of ethics is thus raised for him, or more exactly, the problem of the ethos corresponding to it, of the response of his own being, action and conduct. … He has to take up a position in relation to this, the only position in relation to this, the only position which can be taken, but a position taken in freedom. It is not that God’s act on and in man makes of him a cog set in motion thereby. The free God does not act thus with man. On the contrary, what the free God in His omnipotence wills and fashions in Jesus Christ in the work of the Holy Ghost is the free man who determines himself under this pre-determination by God, the obedience of his heart and conscience and will and independent action. Here man is taken seriously and finds that he is taken seriously, as the creature which is different from God, which is for all its dependence autonomous before Him, which is of age. Here he is empowered for his own act, and invited, commanded and encouraged to perform it (35).

The human person is set in an immediacy of relation with their God from whose direct command they cannot escape. They have been snatched from the power of sin and death, liberated from their own impotence, and freed from their assumed autonomy whereby they were supposedly ‘free’ alongside God; God has ‘beset them behind and before’ (cf. Psalm 139:5).

Fourth, the beginning of Christian life is the beginning of a person’s life in a distinctive ‘fellow-humanity.’ That is, the Baptism with the Holy Spirit sets a person in the Christian community where they become the companion and fellow of others who themselves are likewise bound to God and so to one another. ‘He ceases to be a self-enclosed man, and there is actualised his relationship to all those to whom Jesus Christ has also attested and imparted himself as Lord and Brother. … He is redeemed from all isolation and also from all contingent or transient attachments to others, and incorporated in the communion of saints (37). The Baptism with the Holy Spirit is not identical with a person’s entry and reception into the Christian community, but it will lead to this. Further, in this community the person will receive their own special spiritual power and their own special task in the total life and ministry of the community (38). These spiritual gifts can never be rigidly defined or limited to institutional offices:

The criterion of the authenticity of the discharge of all institutional office in the Church is always and everywhere the question whether the one who serves in this or that office is a recipient and bearer of the charisma indispensable to his work, and first and finally whether he is a recipient and bearer of the love which is above all spiritual gifts. At no time, then, in the life and ministry of the community, in the fulfilment of Christian fellow-humanity, can one dispense with the petition: Veni Creator Spiritus. Always and everywhere this must be prayed afresh.

Finally, the Baptism with the Holy Spirit is only the beginning of the Christian life, a beginning which must be ever-renewed in its always fresh continuation. Just as the seasons are always renewed, so the fruit-bearing Christian life is ever renewed, and so requires ever-new sowing and reaping, cultivation and pruning, a daily penitence and striving for those new possibilities which lie ahead (39). The whole of the Christian life is one long Advent-season, a life of ‘waiting and hastening’ (2 Peter 3:12) toward the ultimate kingdom, in prayer and eucharist, caught up in the movement of God: ‘the power of the life to come is the power of his life in this world’ (40).