Mark’s Passion Narrative (3) Jesus is going to die. He knows it, and somehow the woman who anointed him knows it. Now events move quickly with Judas enacting a conspiracy to betray Jesus to the chief priests. You can read the passage here.

Jesus is going to die. He knows it, and somehow the woman who anointed him knows it. Now events move quickly with Judas enacting a conspiracy to betray Jesus to the chief priests. You can read the passage here.

Already in Mark 3:19, Judas Iscariot—Judas from the village of Karioth (Lane, The Gospel of Mark [NICNT], 136)—has been introduced as the last of the twelve disciples chosen by Jesus to accompany him and learn his way of life and service, and identified as the one “who also betrayed him.” The word used in 3:19 and twice in 14:10-11 is paradidõmi which means simply ‘to hand over or deliver’ and in this instance ‘to betray.’ Judas will hand Jesus over to the authorities, helping them in their wish to arrest him stealthily and avoid a riot (vv. 1-2). Further, Jesus is perhaps hard to locate when not in public (cf. John 11:57). Thus, Judas is seeking an opportune time to hand him over, away from the public gaze.

In 9:31 and 10:33 (twice) Jesus also uses paradidõmi to speak of his being handed over to be condemned to death. These ‘passion predictions’ indicate that Jesus is aware of his impending death—and of the resurrection which will follow. As such, this ‘handing over’ is in accordance with God’s purpose. That Judas now enacts his conspiracy is his decision and choice and yet somehow, it is also the fulfilment of the divine plan already announced. This does not diminish the pathos of the account: “then Judas Iscariot, who was one of the twelve…” In Mark’s Gospel we are not given any motive for Judas’s betrayal and are left wondering that one of Jesus’ closest associates could act in this way.

The sense of the unfolding of a divine plan continues in the strange story of verses 12-16. Mark begins with a timestamp which proves a little confusing. The anointing at Bethany is preceded with a similar note, that the Passover and (feast of) Unleavened Bread is two days away. Now in verse 12 it is the first day of Unleavened Bread “when the Passover was being sacrificed.” Technically, Unleavened Bread follows Passover on the fifteen of Nisan, but Mark appears to conflate the two feasts, for the Passover lambs were sacrificed on Nisan fourteenth and the Passover eaten that evening. It helps to recall that in Jewish time, the new day started at sunset, and so the transition from the fourteenth to the fifteenth occurred in the early evening. Further, it may be that Mark is merely repeating an understanding in which, in the popular mind, the two feasts were regularly conflated (e.g. Lane, 497).

More complicated is the realisation that in John’s account, Jesus’ final meal occurs before the Passover feast (John 13:1) and Jesus dies on Nisan 14 as the Passover lambs are being sacrificed (John 19:14, 30-31, 42). Has John sacrificed historical accuracy here, in support of a theological statement about Jesus, the Lamb of God? Or is John’s account more likely—with the result that Mark and the other Synoptic gospels have mistakenly called Jesus’ last meal a Passover meal when in fact it preceded the Passover? Or is there some way of reconciling the accounts so that both Mark and John are historically accurate accounts? Scholars have canvassed all three options of what Lane (497) has called “one of the most difficult issues in passion chronology,” although none of the proposals are entirely satisfactory.

Whatever the answer to this historical problem, it cannot be doubted that Mark portrays the meal as a Passover meal. In verse 12 when the lambs are being sacrificed, the disciples ask Jesus where he would like to eat the Passover. Verses 14 and 16 clearly state that they prepared the Passover meal in accordance with his instructions. The description of the meal also includes several features that mark it as a Passover celebration (Lane, 498; Morna Hooker, The Gospel according to Saint Mark [BNTC], 333).

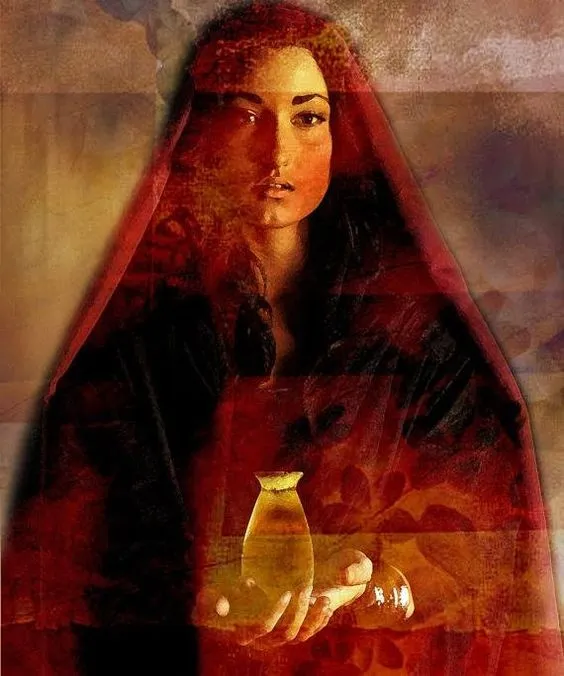

The story itself is reminiscent of the mysterious story of Mark 11:1-7, about the colt for Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. The disciples obviously assume that they will keep the feast and so approach Jesus with their question. Jesus’ response is cryptic: they are to go into the city, follow a man carrying a pitcher of water (typically a woman’s role and so somewhat unusual), and tell the owner of the house that the man enters, “The Teacher says, ‘Where is my guest room in which I may eat the Passover with my disciples?’”

How did Jesus know? The whole episode has the sense of the prophetic, of divine control, of Jesus being assured and in control of the unfolding events. It may be, of course, that he knew the owner of the house and the owner knew him as ‘the Teacher.’ And perhaps too he knew the habits of the servant. This seems less than likely, however, for then he could have sent the two disciples directly to the house. Rather, Jesus has prophetic insight and is being led in his ministry, even in so mundane a task. We might say, although Mark does not say it like this, that Jesus is being led by the Holy Spirit—and his disciples are observing and learning.