Barth’s Doctrine of God in Church Dogmatics Volume II/1

Barth’s Doctrine of God in Church Dogmatics Volume II/1

McCormack argues that Karl Barth has developed a post-metaphysical—i.e. Christological—doctrine of the divine being in which God assigns his own being to himself, and constitutes himself as triune, in the singular event of divine election. That is, God is who and what he is only in this decision. The result of reading Barth in the way McCormack does is that he can assert (a) that there is no immanent trinity prior to this divine determination of God’s own being; and (b) there is no “eternal Son” as such, that is, no eternal Son who has an existence independent of and prior to the divine determination that the Son’s being would consist in his union with humanity.[1]

McCormack turns to Church Dogmatics II/1 where Barth discusses “The Being of God in Act.” Barth agrees with Augustine, Aquinas and the Protestant scholastics that God is actus purus: the living God whose very essence is life. But Barth wants also to go further and insist that God is actus purus et singularis.[2] McCormack interprets this in terms of Barth’s later statement: “No other being exists absolutely in its act. No other being is absolutely its own, conscious, willed and executed decision.”[3] He goes on:

This is why God is actus purus et singularis. The eternal act in which God determines to be God-for-us in Jesus Christ and the act in time in which this eternal act reaches its (provisional) goal are a “singular” act, an act utterly unique in kind. God is what he is in this act—which is not true of anyone or anything besides God.[4]

God is what he is in the eternal act of divine election in which God determined his own being as God for and with us in the covenant of grace. Indeed, God is Jesus Christ in his second mode of being, not simply the “eternal Son.” McCormack argues that Jesus Christ can be both the electing God (i.e. the subject of the decision of election) as well as the consequence of the decision of election because in Barth’s view of the triune God there is but a single subject, whether in the mode of being of Father or of Son. Thus the decision which constitutes the person of Jesus Christ—and also the eternal Son—is also his decision because as the one God he participates in the sole divine subjectivity. McCormack is aware that he is straining the limits of language and logic:

Logically, the “transformation” of a Subject into another mode of being cannot be carried out by a Subject who already is that mode of being; otherwise no “transformation” has taken place at all. In truth, however, Barth’s claim will never be understood where we rest content with playing with the logic of Subject-object relations. What is happening here is quite simply a refinement of Barth’s earlier doctrine of the Trinity.[5]

Instability in Barth’s Doctrine

McCormack argues that Barth’s concept of the eternal being of God was altered as a consequence of his mature Christology. Barth, he notes, actualised and historicised the being of Christ, and so also of God. In so doing he preserved the immutability of God while jettisoning divine impassibility and timelessness. (Here McCormack reiterates his contention that Chalcedonian Christology remained in some ways ambiguous in its treatment of Christ’s person, and in other ways is not wholly sufficient for contemporary Christological reflection. See my earlier posts in this series on Chalcedonian Christology and Barth’s Historicised Christology.)

In the next sections of his essay, then, McCormack identifies three aspects of Barth’s doctrine of God in II/1 in which the Swiss theologian still works within the frame of a classical metaphysic to some degree at least, which produces, in McCormack’s view, instability and incoherence in his earlier doctrine. McCormack traces this instability to Barth’s desire to retain God as God, to secure the divine freedom of God from us and for us. Thus, he speaks of God’s “immutable vitality” as something that God possesses in himself above and beyond the “holy mutability” assigned to the attitudes and actions of God in the coming of Jesus.[6] So, too, the power of God, his divine omnipotence, is viewed in II/1 as something prior to and above his work of creation and redemption, etc. God could have been omnipotent in a different form. After his doctrine of election, however, Barth says, “May it not be that it is as the electing God that He is the Almighty, and not vice versa?”[7] McCormack finds great significance in the vice versa of this citation, where the “door is firmly closed against the possibility that election…will be seen as simply one possibility among others available to a God whose omnipotence has been defined in abstraction from what he has actually done in Jesus Christ.[8] Such is the case also with God’s knowledge and will.

There is an instability at the heart of Barth’s treatment of the being of God in Church Dogmatics II/1—an instability which finds its root in the belief that to God’s “essence” there belongs both a necessary element and a contingent element. … To define the “essence” of God in terms of both necessity and contingency, of immutability and mutability, of absoluteness and concreteness is to allow both elements in these pairs to be canceled out by the other. An essence that is contingent, mutable, and concrete is not and cannot be necessary, immutable, and absolute—unless God is necessary, immutable, and absolute precisely in his contingency, mutability, and concreteness. Where the two are allowed to fall apart as polar elements, the result can be only incoherence.[9]

The reason for this instability in Barth’s doctrine lies in the fact that Christology does not control his theological ontology. Once Barth has reworked his doctrine of election in Church Dogmatics II/2, these kinds of tensions are, says McCormack, eliminated.

[1] In fact, McCormack quite openly notes that “what I offer in the pages that follow is a reconstruction—what Barth ought to have said, had he followed through, of the ontological implications of his revised doctrine of election with complete consistency.” See McCormack, “Actuality of God,” 211, emphasis added; cf. also pp. 211-213, 215, 234, 237-239.

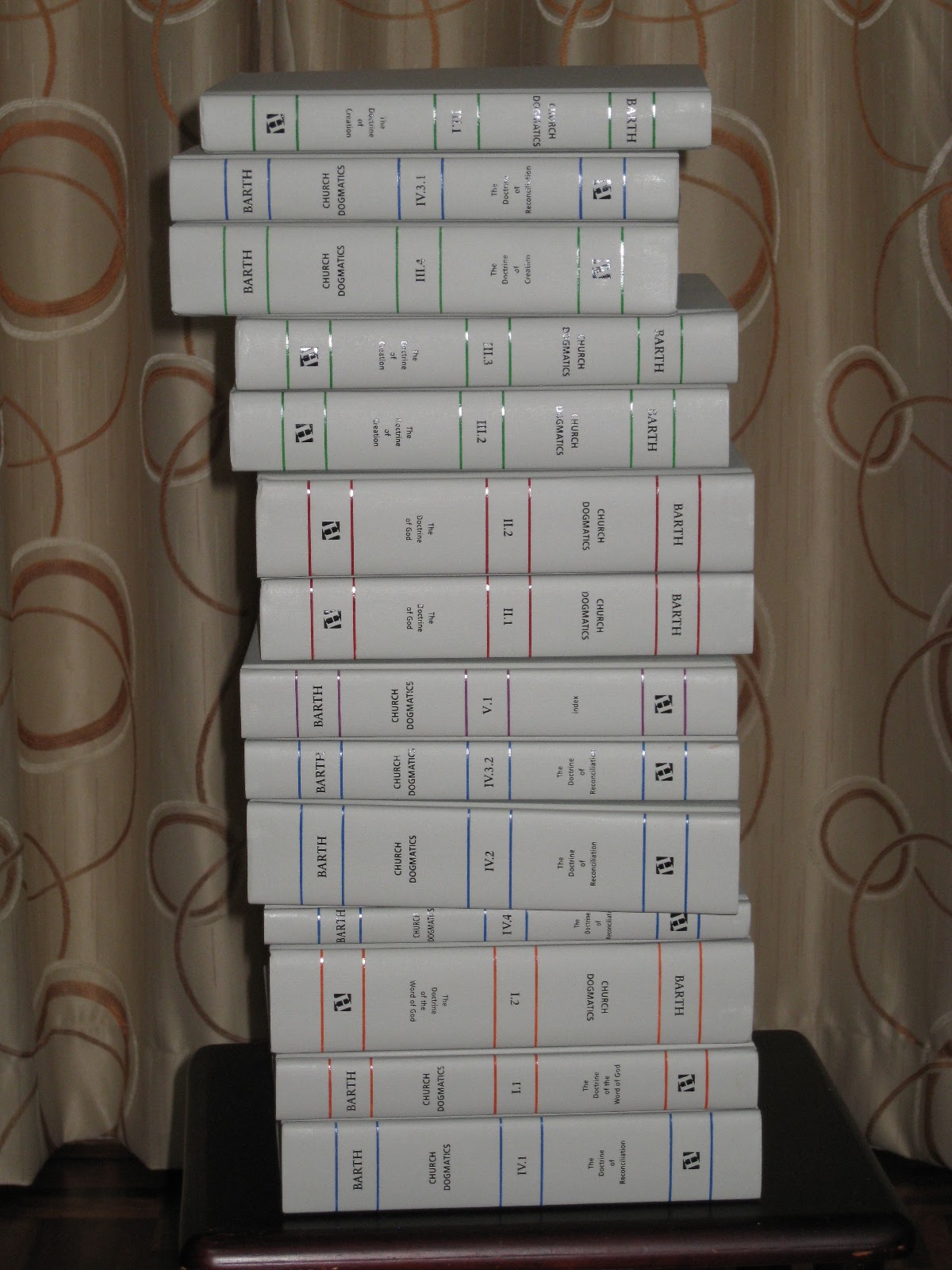

[2] Barth, Karl, Church Dogmatics II/1: The Doctrine of God, ed. Torrance, G. W. Bromiley & T. F., trans., T. H. L. Parker, W. B. Johnston, H. Knight, J. L. M. Haire (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1957), 264.

[3] McCormack, “Actuality of God,” 215. McCormack is citing Barth, Church Dogmatics II/1, 271, though the emphasis is his.

[4] McCormack, “Actuality of God,” 215, original emphasis.

[5] McCormack, “Actuality of God,” 218.

[6] McCormack, “Actuality of God,” 233.

[7] Barth, Karl, Church Dogmatics II/2: The Doctrine of God, ed. Torrance, G. W. Bromiley & T. F., trans., Bromiley, G. W. (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1957), 45.

[8] McCormack, “Actuality of God,” 236.

[9] McCormack, “Actuality of God,” 237-238, original emphasis.

Nearly all the wisdom we possess,

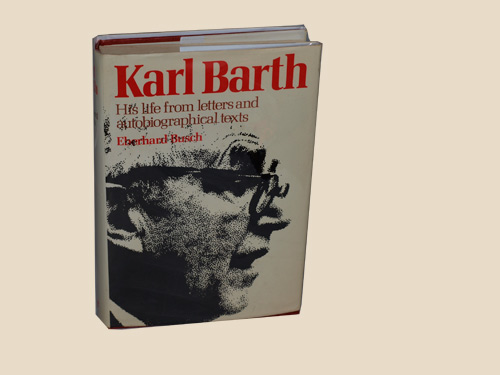

Nearly all the wisdom we possess, I already have all of these in real books, but it is a very good introductory special for those who want or like digital versions. There are selections from across the decades of Barth’s career, from the early 1920s through to a few final pieces from shortly before his death in 1968. Some of them are major works – The Münster Ethics (1928), Barth’s Gifford lectures The Knowledge of God and the Service of God (1937-1938), and Theology and Church, a collection of essays from 1920-1928. Others are occasional pieces, including lecture series, sermons, short theological pieces, and Barth’s tribute to Mozart, with whom he carried on a life-long love affair. Also included in the set is the massive biography by his friend and student Eberhard Busch, which I have reviewed in three posts under the title of

I already have all of these in real books, but it is a very good introductory special for those who want or like digital versions. There are selections from across the decades of Barth’s career, from the early 1920s through to a few final pieces from shortly before his death in 1968. Some of them are major works – The Münster Ethics (1928), Barth’s Gifford lectures The Knowledge of God and the Service of God (1937-1938), and Theology and Church, a collection of essays from 1920-1928. Others are occasional pieces, including lecture series, sermons, short theological pieces, and Barth’s tribute to Mozart, with whom he carried on a life-long love affair. Also included in the set is the massive biography by his friend and student Eberhard Busch, which I have reviewed in three posts under the title of