Leal, Dave, On Gay Marriage (Cambridge: Grove Books, 2014) pp. 27

ISBN: 978-1-85174-906-5

This is a booklet rather than a book, part of the Grove Ethics series (E174). Dave Leal teaches at Oxford in the Philosophy, and Theology and Religion departments. Written in 2014 soon after the passage of the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013, it deals with and alludes to issues more familiar with the British context than I am. The brief format of the series means that it is quite compressed in style, as Leal includes more ideas in the work than he can clearly explain—though that is very possibly more my shortcoming than his.

The booklet is divided, after a one page introduction, into three chapters of roughly equal length. The first is entitled “Gay,” the second “Marriage,” and the third “Gay Marriage.” The first chapter opens with the apparently controversial statement that “Christians can live without gay.” He quickly proceeds, however, to an equivalent statement that “Christians can live without straight.” It is the practice of mapping human being according to various purported sexualities that he finds problematic. Leal explores the connection between “sexuality” and identity, and indeed challenges the reality and relevance of the notion of “sexuality” at all, understood in terms of identifying or labelling either oneself or others according to sexual preferences or practices as though these are part of a person’s “essence.” A Christian perspective on identity, he suggests, must be grounded primarily in our fundamental relation to God, in the light of which all other identity commitments are provisional.

The second chapter plumbs the meaning of marriage, which Leal intentionally de-centres as a primary mode, at least of Christian life. The focus of the chapter is much more on legal questions with metaphysical questions concerning the nature of marriage bracketed. The reason for this is that marriage takes and has taken different forms in different cultures and historical periods; there appears to be no “essence” of marriage accessible to public reason, although it is true that different groups have what John Rawls has termed a “reasonable comprehensive doctrine” of marriage. Thus multiple legal patterns of marriage have emerged in different jurisdictions. This is not to say that marriage across jurisdictions does not share some central ideals, and Leal identifies three as primary—sexual exclusivity, permanence, and consent. Noting these features, Leal suggests that the “goods” of marriage might be articulated in terms amenable to public reason and the “human good,” as a guide to those responsible for drafting legislation, that it serve this human good. An important issue addressed in this chapter asks whether marriage is simply a cultural-legal matter which may change in accordance with social and cultural shifts. Does marriage “evolve,” as suggested by one minister in the British parliament? Leal comments:

It is certainly a matter of historical fact that once there was Marriage [according to the Marriage Act 1754], and later there was Marriage [according to the Marriage Act 1949], but this does not suggest that marriage evolves. Perhaps all the Culture Secretary meant was that we change our minds about what we mean by marriage, which would not, of course, be a comment about marriage at all (16).

Perhaps metaphysical questions about the nature of marriage cannot be bracketed after all.

Having laid the foundations of his discussion in the first two chapters, Leal now asks, What, then, of gay marriage? and asserts that, “Christians have no reason to expect marriage laws accurately to reproduce their own conception of marriage” (18). Leal is no doubt correct in this assertion, particularly given the secular, liberal-democratic context in which he writes—a context shared by Australia.

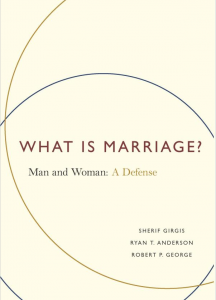

However, he is unprepared to leave it at that, and offers arguments to suggest that changing marriage laws to affirm same-sex marriage may not be a good idea. He argues, on the basis of consequences deriving from liberalisation of divorce laws, that it is simply not the case that liberalising marriage laws to include gay couples will have no real impact on heterosexual marriage—or marriage itself. Further, marriage was never conceived as a form of relationship for heterosexuals in any case; “Who, after all, believed in heterosexuality before the nineteenth century?” (19). Marriage, as a form of human relation, pre-exists any human laws regulating it, and arguably, any religious development as well.

Marriage was traditionally conceived as a form of relationship binding male and female, accepting the biological relation between the two, along with the form of natural sexual reproduction of humans, as a reality to which marriage corresponds. This conception may arise from a religious perspective . . . or it may simply be rooted in a sense of respect for the natural, without any additional religious dimension. This appeared to be the main conviction of those who identified themselves as homosexual but opposed changes to permit same-sex marriage. Those who opposed the introduction of same-sex marriage did not principally see marriage as answering to the particular appetites and identities of types of people (19).

This concern with creaturely reality, especially with respect to procreation and childcare (though this is a point not developed by Leal), suggests that marriage itself is something, that it is grounded in the nature of how things are, and thus not simply “what we say it is,” or the mere creation of legislation.

“Marriage is what we say it is” would separate marriage from that conception of human reality it has traditionally been seen to belong to. If that conception of reality is deemed to belong to a comprehensive doctrine not defensible in public reason—or dismissed as merely the present mood of past centuries—it is not at all clear that the alternative conceptions of reality, such as the sexuality map . . . are in fact any more publicly defensible. The result looks unlike discernment, and more like the choice of a different doctrine, the triumph of a different partiality. The loss, then, is perhaps precisely that of tradition, and if that is indeed lost, to be replaced by mere legislative contingencies, the harm done to marriages by that move remains to be seen. There were never any winners here though. If a stated aim was to open up marriage to same-sex couples, but in doing so marriage necessarily lost its original meaning, we may wonder whether anyone has made a significant gain (20).

One may guess that the long-term effect of the recent changes to marriage will be to reinforce the conception of it as a creature of the legislator’s and participant’s wills, and therefore make it more fragile as a social institution, and more readily rejected, with unfortunate consequences for those that the institution might be concerned to protect (24).

This is a thoughtful essay attempting, successfully for the most part, to contribute a reasoned argument in non-sectarian terms to an issue fraught with tension in the public sphere. Leal includes many more ideas than could be expansively developed in the format of this series, but what he has developed is worth careful consideration.

Volf & Croasmun have a bit of fun critiquing critique, and introduce a new term coined by Christopher Castiglia to describe the “unmistakable blend of suspicion, self-confidence, and indignation” sometimes found in those who love to critique others, especially traditional biblical interpretations and theological formulations.

Volf & Croasmun have a bit of fun critiquing critique, and introduce a new term coined by Christopher Castiglia to describe the “unmistakable blend of suspicion, self-confidence, and indignation” sometimes found in those who love to critique others, especially traditional biblical interpretations and theological formulations.