James 1:13

James 1:13

No one, when tempted, should say, ‘I am being tempted by God,’ for God cannot be tempted by evil and he himself tempts no one.

With this verse James transitions from peirasmos as trials to peirasmos as temptations. In fact, many commentators identify the transition by translating the text, “Let no one say when he is tested, ‘I am being tempted by God.’” It is worth noting that James would certainly draw a distinction between God testing his people and God tempting his people. The Old Testament has many accounts of the former, from the test established in the Garden of Eden, to Abraham’s test in Genesis 22, to Israel’s tests in Exodus 16 and Deuteronomy 8, etc. It is certainly the case that one’s faith is regularly tested as we noted in our comments on verses 2-4. It is certainly the case that God will at times test particular individuals, either through the circumstances they face (e.g. Psalm 105:17-19) or by presenting them with a particular challenge (John 6:5-6). Nevertheless James insists that God never tempts his people. The verse begins with an imperative followed by two supporting reasons. James’ command is very simple: whenever one is tempted one must not blame God for it as its source or origin.

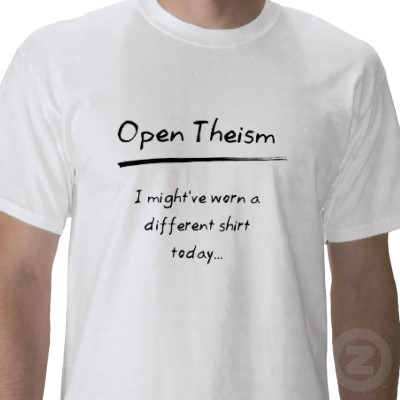

Why might someone assign the source of our temptations to God? Perhaps they have a theological perspective in which God is the ultimate cause of all things, even if he uses secondary agents. If we believe God is the source of our trials and temptations, we may be less likely to resist them, and more likely to be double-minded with respect to prayer. Some people may indulge in the temptation, justifying their sinful actions by claiming it is God’s will (cf. Romans 6:1-2). James will have none of this and insists that no one assigns responsibility for temptations to God. Here, there is no place for divine omni-causality.

Instead, James grounds his imperative in a twofold reflection on God’s character. First, God cannot be tempted with evil (ho gar theos apeirastos estin kakōn). The key word, apeirastos is found only here in the New Testament, and may have been coined by James (Vlachos, 43). Several translations have been suggested. It may mean simply that God is not temptable, that his supreme holiness denies any place whatsoever to evil; or it may mean that God is inexperienced and therefore “untouched” (NEB) with respect to evil; or, as Davids (82-83) has suggested recalling the command of Deuteronomy 6:16, God ought not to be tempted by evil people. In the immediate context here, the first possibility is usually chosen by translators and commentators. The second possible meaning requires changing apeirastos to the more commonly used aperatos, while Davids’ suggestion does not do justice to the balanced movement of thought in the verse whereby James’ second rationale (“and he himself tempts no one”—peirazei de autos oudena) issues from the first: God cannot be tempted, and he does not tempt any. Thus God’s supreme holiness precludes his being tempted; evil has no foothold or place in God. Because this is true, neither does his holiness entice others towards evil for this would be utterly alien to his holy nature. Further, we see once more that for James, God is wholly and single-mindedly good (cf. v. 17). God remains the gracious and generous God whose will is to bless his people.