It has been quite some years since I last read Ezekiel, and at that time I found myself asking, “Will this book ever end?” One of the benefits of intentionally reading through the whole Bible is that you will read even those bits you may have avoided! This time around, I find Ezekiel captivating, absorbing. The book has not changed; I must have!

It has been quite some years since I last read Ezekiel, and at that time I found myself asking, “Will this book ever end?” One of the benefits of intentionally reading through the whole Bible is that you will read even those bits you may have avoided! This time around, I find Ezekiel captivating, absorbing. The book has not changed; I must have!

This morning I read chapter 23, the story of Oholah and Oholibah, two infamous sisters representing Samaria and Jerusalem, respectively. The prophecy is of brutal judgement on Jerusalem, similar to what occurred in Samaria. The allegory portrays the two kingdoms as wanton, prostituting themselves for favours and pleasure, but ultimately despised, mis-treated, and even killed by their lovers. Yahweh handed the Northern Kingdom of Israel over to the Assyrians. He will abandon Judah and Jerusalem to the Babylonians.

The language and imagery of the prophecy is sexually explicit, violent, and female. The two cities are portrayed as licentious women whose adulteries signify their alliances with foreign powers, and their participation in the nations’ idolatries. They lust after the ‘big swinging dicks’ of Assyria and Egypt—I read the chapter in the Jerusalem Bible where the translation of verses 19-20 is particularly vivid:

She began whoring worse than ever, remembering her girlhood, when she had played the whore in the land of Egypt, when she had been infatuated by profligates big-membered as donkeys, ejaculating as violently as stallions.

But the behaviour of these sisters is intended to disgust:

They have been adulteresses, their hands are dripping with blood, they have committed adultery with their idols. As for the children they had borne me, they have made them pass through the fire to be consumed. And here is something else they have done to me: they have defiled my sanctuary and have profaned my sabbaths. The same day as sacrificing their children to the idols, they have been to my sanctuary and profaned it. Yes, this is what they have done in my own house (vv. 37-39).

Thus, Yahweh calls for the sisters to be judged, violently shamed, and destroyed. They will be stoned, and hacked with the sword. They will be robbed, stripped, and left naked, their noses and ears cut off, their children slaughtered, their houses set on fire.

What are we to make of this language and imagery, of this kind of passage in the Holy Bible? I have not read any commentaries or studies on Ezekiel, nor any feminist interpretation or criticism of the passage. In light of the ongoing problem of violence against women in Australian society, I imagine that some will find this text distressing or offensive. Others will be at a loss; some, perhaps, will move on quickly to less disturbing, more amenable readings. How do we make sense of a passage like this?

Although I am a novice with respect to Ezekiel, I can offer some reflections. First, we must remember that the passage is an allegory and is speaking not of women per se, but of nations—the two kingdoms of Israel and Judah, and their capital cities, Samaria and Jerusalem. The imagery is metaphorical, and the (truly terrible) judgement is directed toward the nations not toward women in particular, although, the horror will fall on the female as well as the male members of these communities.

Second, the use of sexual language to portray covenantal faithfulness and faithlessness is not uncommon in the prophets (see, for example, Jeremiah 2-5; 31; Hosea 1-3; Ezekiel 16; cf. Song of Solomon). The covenantal relation between God and Israel is understood in terms of a marriage, with fidelity and betrayal understood spiritually rather than literally. Israel’s ‘adultery’ is its idolatry, its giving itself to another lord other than Yahweh. Ezekiel has laboured this point continually in his earlier chapters.

Nevertheless, that such explicit language and imagery is used in this passage suggests that rampant sexual immorality was also an issue in Judah, accompanying the practice of idolatry and the fruits of prosperity. Further, that Ezekiel intends to indict the women of Judah for their immorality is suggested in verse 48: “I mean to purge the land of debauchery; all the women will thus be warned, and ape your debauchery no more,” though I acknowledge that this reference to other ‘women’ could also be a reference to nations.

But why would Ezekiel target women with this criticism? Shouldn’t he more appropriately aim this criticism at men? Actually he does, in chapter 22:

Where there are people who eat on the mountains [= idolatry] and couple promiscuously [note the link between idolatry and sexual promiscuity]; where men uncover their father’s nakedness; where they force women in their unclean condition; where one man engages in filthy practices with his neighbour’s wife, another defiles himself with his daughter-in-law, another violates his sister, his own father’s daughter… (vv. 9-11).

The men, too, are condemned for their sexual activity, using language that suggests that they have abused their power, at times violating and forcing themselves on women. It is a truism that it ‘takes two to tango,’ but in some of these cases it was not the tango but rape. Nevertheless, sometimes and perhaps often, women were equal or willing participants in the activity, and Ezekiel has condemned both men and women for their immoral conduct, though admittedly, his language in the twenty-third chapter is more lurid.

This leads to a third observation: the prurient language used in this chapter might lead some to picture this predominantly as a female sin. This, of course, is nonsense and misrepresents the nature of the issue (it takes two…). Nevertheless, Christian history—and not merely Christian history—has repeatedly left the impression that female sexuality is dangerous, that women are wanton, wickedly seductive, and thus in need of corralling, suppression, and harsh treatment if they are caught acting ‘inappropriately’—however a particular culture will define that. This is problematic and has often led to the suppression of women per se, and not merely the ‘inappropriate’ activity concerned. Further, this perspective can used to legitimise the use of violence against women in the interests of deterrence, of redeeming the group from shame, of preserving or restoring one’s affronted honour, and so forth.

Here we arrive at the nub of the problem I raised earlier: the imagery used portrays God using retributive violence against the sisters which seems to legitimise such violence against women. And here, I can only note that (i) he is speaking of nations, not of women; (ii) that this is a prophecy of divine judgement which is a divine prerogative—and here we must consider the divine abhorrence of the kinds of sins clearly delineated in Ezekiel; (iii) that the text is clearly allegorical and imaginative, not meant to be taken with a wooden literalness; and (iv) that other texts, especially Malachi 2:17, declare God’s hatred with respect to male-on-female violence. I might also note that in Ezekiel’s culture, it is the male who acts publicly, who wields power. By identifying the nation as a degenerate woman, the prophet is mocking and shaming the men. These observations only serve to place this problem in a larger setting, and do not fully mitigate the issue. Unfortunately, those bent on abusing their power will likely seek any justification they can for their actions, and fail to heed any interpretation that challenges their assumption.

Finally, as we think of the implications of this passage for contemporary application, the analogy is properly applied to the church rather than a modern nation-state, for it is the church who are God’s covenanted people. The church, therefore, is warned against throwing herself at the world, seeking its favours and pleasures, selling its soul and body for its approval. God’s terrible judgement was directed against his people—something we dare not forget.

Photo Credit:

Elena Maximova in Carmen (Royal Opera House), October 2015

Photo by Catherine Ashmore; Posted by Opera Montajes

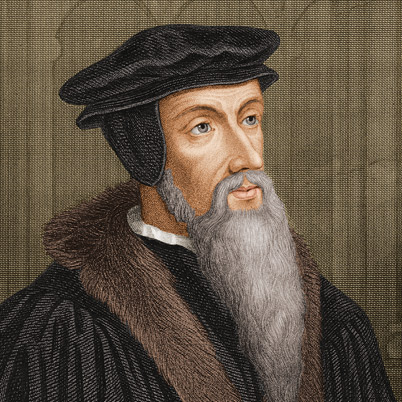

I came across this note as I read a little of Calvin this evening. I was in the Institutes I:14:iv on the doctrine of creation where Calvin is beginning his discussion of the angels. He writes to head off the kind of teaching that indulges in endless curiosity and speculation not tethered to Scripture. His words are still apt today:

I came across this note as I read a little of Calvin this evening. I was in the Institutes I:14:iv on the doctrine of creation where Calvin is beginning his discussion of the angels. He writes to head off the kind of teaching that indulges in endless curiosity and speculation not tethered to Scripture. His words are still apt today: One joy in life for Monica and me at the moment is watching our grandsons grow from little babies to little boys. Each so beautiful. So energetic. So curious. So full of life and learning. So unique.

One joy in life for Monica and me at the moment is watching our grandsons grow from little babies to little boys. Each so beautiful. So energetic. So curious. So full of life and learning. So unique.