I have not preached this sermon, but prepared it to see how I might approach this passage if I were called upon to preach it in a congregational context. Moving from exegesis to exposition is not always easy, and I am not overly happy with this sermon as it presently stands. Hopefully it would be developed and improved as I prepared it with a specific audience in mind. Perhaps its focus would be sharpened, and story, illustration and application would bring this somewhat cerebral text to life.

I have not preached this sermon, but prepared it to see how I might approach this passage if I were called upon to preach it in a congregational context. Moving from exegesis to exposition is not always easy, and I am not overly happy with this sermon as it presently stands. Hopefully it would be developed and improved as I prepared it with a specific audience in mind. Perhaps its focus would be sharpened, and story, illustration and application would bring this somewhat cerebral text to life.

*****

The Two Loves

I am not sure I agree with the way Monica tells the story, but here goes…

We had been married a little under two years, had recently returned home from a six-month short-term mission experience in Indonesia, had our first baby, and were preparing to move to rural WA for our first pastoral appointment. I was obviously tired and had gone to bed earlier than Monica—after working hard all day, and then preparing sermons into the evening, I might add! When Monica came in I was asleep, but apparently half sat-up, turned, looked at her, eyes open and asked, “What’s the password?”

“What password? What do you mean?”

“What’s the password?”

Realising that I was still asleep even though sitting half upright and talking (it had happened before, unfortunately, and to my everlasting shame!), she said again, “I don’t know what the password is. You’ll have to tell me the password.” To which I replied—apparently in a deep, husky voice, “Desire!”

For some reason, Monica still thinks that’s a funny story and loves to re-tell it, even thirty years later! She leaves out, of course, the most important point: the reason the word desire was so prominent in my mind…

Desire. What kinds of things do you desire? Do your desires run in good directions? No doubt some of them do. But our desires, typically, are a mixed bag of good and not-so-good. Our passions can shape the direction of our life for extraordinary achievement or they can run amuck. James turns his attention to these things in our passage this week.

Read the text: James 1:12-18

Human Passions

In verse 13 James takes aim at an attitude that was evidently a problem amongst his listeners, who were blaming God for the troubles and temptations they were experiencing. Instead of “the devil made me do it” they were saying, “God is making me do it!”

It is convenient to attribute our temptations to God. If God is tempting us, we can hardly be blamed for giving in to the temptation. No, in fact, we would be doing God’s will by giving in! Although we might think this is all a bit silly, it is not all that uncommon for someone to justify their behaviour—sometimes even unconscionable behaviour—by claiming God had led them into it, that God has a higher purpose for them, and this activity is part of a bigger plan, that God has spoken to them, that God is love and surely he would not want them “suffer” any longer. Actually, it is amazing how easy it is to justify even sinful behaviour by attributing some blame to God.

In our text, however, the situation is probably a little different. James’ hearers are undergoing real suffering and hardship, very possibly economic oppression and marginalisation, and they are angry. Perhaps they want to take matters into their own hands, and strike out at those who are oppressing them. With bitterness of spirit they are blaming God for their troubles, and perhaps even suggesting that God wants them to rise up against their oppressors.

“Let no one say when he tempted, ‘I am tempted by God.’” James rejects this position out of hand, because God is always and only good, and he never changes. God cannot be tempted with evil for in himself, God’s goodness is his holiness and he is beyond temptation. Further, God’s will is that his people also be holy, so why would he tempt them to evil? For James, the very idea is ridiculous. Perhaps we are tempted, then, by the devil? But no, in this case James does not go there either, but lays the responsibility squarely at our own feet. We are responsible: “each person is tempted when he is lured and enticed by his own desire.”

Desire in and of itself is not necessarily wrong. We can desire good things, both for ourselves and for others. Our passions can be noble. This weekend in Perth we have seen the results of noble passions, with the “giants” who have visited our city to open this year’s Perth International Arts Festival. A passion for art, creativity and excellence resulted in a series of street festivals as hundreds of thousands of people turned out to enjoy the spectacle of the giants. This week in Perth we have also seen the results of ignoble passion, again in the arts, with the opening of Fifty Shades of Grey in the cinemas, exploiting prurient interests and celebrating dominance and power.

James is familiar with the dual nature of our passions and draws on ancient Hebrew concepts to set forth his understanding of the nature of sin. The Hebrews believed that two impulses are at work in the human person, the yetzer hara‘ and the yetzer hatov. The first yetzer is the evil impulse, and the second is the good impulse. Our impulses, desires and passions can run in either direction, and when they run with the yetzer hara‘ we are lured into sin, enticed by a particular kind of bait, and snared in the trap of sin. Our own desires lead us into a trap. One commentator says that we are “hooked by own bait.”

James gives a biological analogy of the birth and development of sin: desire “conceives” and “gives birth” to sin. But sin is not the end of the story. The sin develops and grows and comes to maturity and eventually “gives birth” to death. We could probably push this analogy too far, and turn it into some kind of “mechanics of sin.” Paul refers to “the mystery of iniquity” which highlights the incomprehensible nature of sin. Nevertheless, if we add intention and action to illegitimate desire, sin results, and if we pursue and persevere in sin “the child grows up” exerting an increasing dominion over our lives. “Make no mistake!” says James: sin is deadly and death-dealing. What appears as a harmless little desire here may grow into a destructive habit or devouring addiction.

Divine Purpose

“Make no mistake!” says James. Illegitimate desire leads to sin, and sin leads to death. We are wrong if we think that this is God’s will for us. God is the lord and giver of life, not the lord and ruler of death! “Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above,” says James, “coming down from the Father of lights.” God is only and always good, insists James¸ and he never changes in this his character and temperament, but only wills and does that which is good. He cannot will evil and does not will evil, and so cannot tempt us with respect to evil. Even God’s judgement, ultimately, is for the good.

James calls God “the Father of lights” which is almost certainly a reference to God as the creator of the heavenly lights—the sun, moon and stars—and so a reference to God’s universal sovereignty and goodness. But God is unlike the heavenly lights that he has created. Whereas they change, even in the midst of their regularity, due to lunar phases and solar eclipses, God never varies in his basic character of goodness, his good intent and purpose. God intends good for his creation, and is kind to the just and to the unjust (Matthew 5:45; Acts 14:17). God intends good for you and for me, which is why he warns us concerning the destructive nature of sin. Even in its fallen and alienated state, God wills the restoration of his creation, rather than its destruction. Yes, God is judge and he will judge the wickedness of humanity as James clearly declares in other passages. But destruction is not God’s purpose. Not only is God creator, he is also the redeemer.

In verse 18 God’s redemptive purpose comes more clearly into focus. “Of his own will,” says James, “he brought us forth by the word of truth that we should be a kind of first fruits of his creatures.” God, the Father of lights, has given us birth! In a daring image, James applies the image of pregnancy and birth to God. God himself has conceived us, carried us and brought us to birth through the “word of truth”—the gospel of our salvation (Ephesians 1:13; Colossians 1:5). Of all God’s “good and perfect gifts,” this is the very best: the redemption and regeneration we have in Jesus Christ by the Holy Spirit so that we have actually become God’s own children! Notice that the whole emphasis is on God’s purpose and God’s activity, and so on grace. James is not teaching a theology of works, but like Paul, is a theologian of grace.

The contrast between God’s will here and human desire in verse 15 is unmistakable. Whereas human desire gives birth to sin and death, God’s will gives birth to life and new creation: we are “born again.” This is language used by Jesus, Peter and John to portray the new life believers have in Christ. Something marvellous, something miraculous occurs when someone becomes a Christian: we are actually, really born … a second time! We are born into God’s kingdom, born into God’s family, born spiritually. This is new life, a new hope, a new beginning, a fresh start, a new creation. You are not who you used to be. I am not who I used to be be. We are not who we used to be.

Scot McKnight, however, reminds us that the new birth is not simply personal. The “us” is corporate, the messianic community, the church. This is a helpful reminder that while salvation is personal, it is neither private nor simply individual, but has a corporate intention and public aspect. Indeed, McKnight goes on to say that,

The “new birth” of James is both intensely personal and structurally ecclesial: God’s intent is to restore individuals in the context of a community that has a missional focus on the rest of the world (131).

God’s ultimate purpose is finally seen in the final phrase of the verse: “that we should be a kind of first fruits of his creatures.” God’s redemptive vision is as large as creation itself. Because God has his eye on the whole of creation, he has brought forth the community of God’s people. The Father of lights has not abandoned his creation but is leading it towards its consummation. Just as God called Abram because he had his eye on “all the families of the world,” so God has brought forth the church, not simply to be the sole recipient of his goodness and blessing, but that through the church, his every good and perfect gift might also be directed to every creature. Such a gracious God is not leading people to fall as some in the community seem to be asserting (v. 13). Rather, the good and gracious God is one who strengthens them to endure the test that God’s purposes for them and for the entirety of the creation might be realised

Our Perseverance

So, make no mistake! Sin is deadly, but God is good. And God has a divine purpose for his creation, including us. Nevertheless, in this life we face troubles without and temptations within. Pressure on the outside, pressure on the inside. But whether without or within, James’ admonition is the same: persevere, hold fast, stand firm, resist!

Every believer is confronted with this choice, whether to give play to their sinful desires or stand firm against them. But James also has a final—and surprising—word of wisdom for us. Standing fast is not a matter of will power or gritted teeth determination. Just as the root of sin is found in desire rather than the will, so the secret of perseverance is found in our desire, in this case, in our desire and love for God.

In verse 12 James reiterates the advice he gave earlier, encouraging his hearers that those who do stand firm will be blessed, and indeed, will receive “the crown of life.” If desire leads to sin which gives birth to death, testing met with perseverance leads to life. In this verse, the crown of life is the final eschatological victory, the hope of eternal life in the kingdom of God. Blessed, not only in time but in eternity. Blessed not only as individuals, but as the community of God’s kingdom in the midst of a renewed creation. This blessing is given, according to James, “to those who love God.” In the final analysis, the Christian life is about who or what we will love. Will we love God, or will we turn our love inward and love ourselves? Augustine and Luther have famously defined sin as homo incurvatus in se—the human being turned in on themselves. But God calls us to a higher love, to love God with all our heart and soul and strength, and to love our neighbour as ourselves.

What does it mean to love God? In broader biblical perspective we see that love for God involves keeping his commandments (John 14:15). It means to keep his word in our hearts (Deuteronomy 6:4-6). In this context, however, it might best be understood in terms of loyalty to God and to God’s will in the face of pressure to compromise and capitulate. It means to look to God, to hope in God, to approach God in prayer, and to trust in God. It means to rejoice in God and find our boasting, joy and life in him. The Christian life is neither a cynical quest for reward nor a fearful avoidance of hell. It is not simply a stoic endurance of affliction or a herculean withstanding of temptation. It is a life of joy rather than gritted teeth, of hope rather than fear, of faith rather than despair, of generosity rather than selfishness, and supremely, of love.

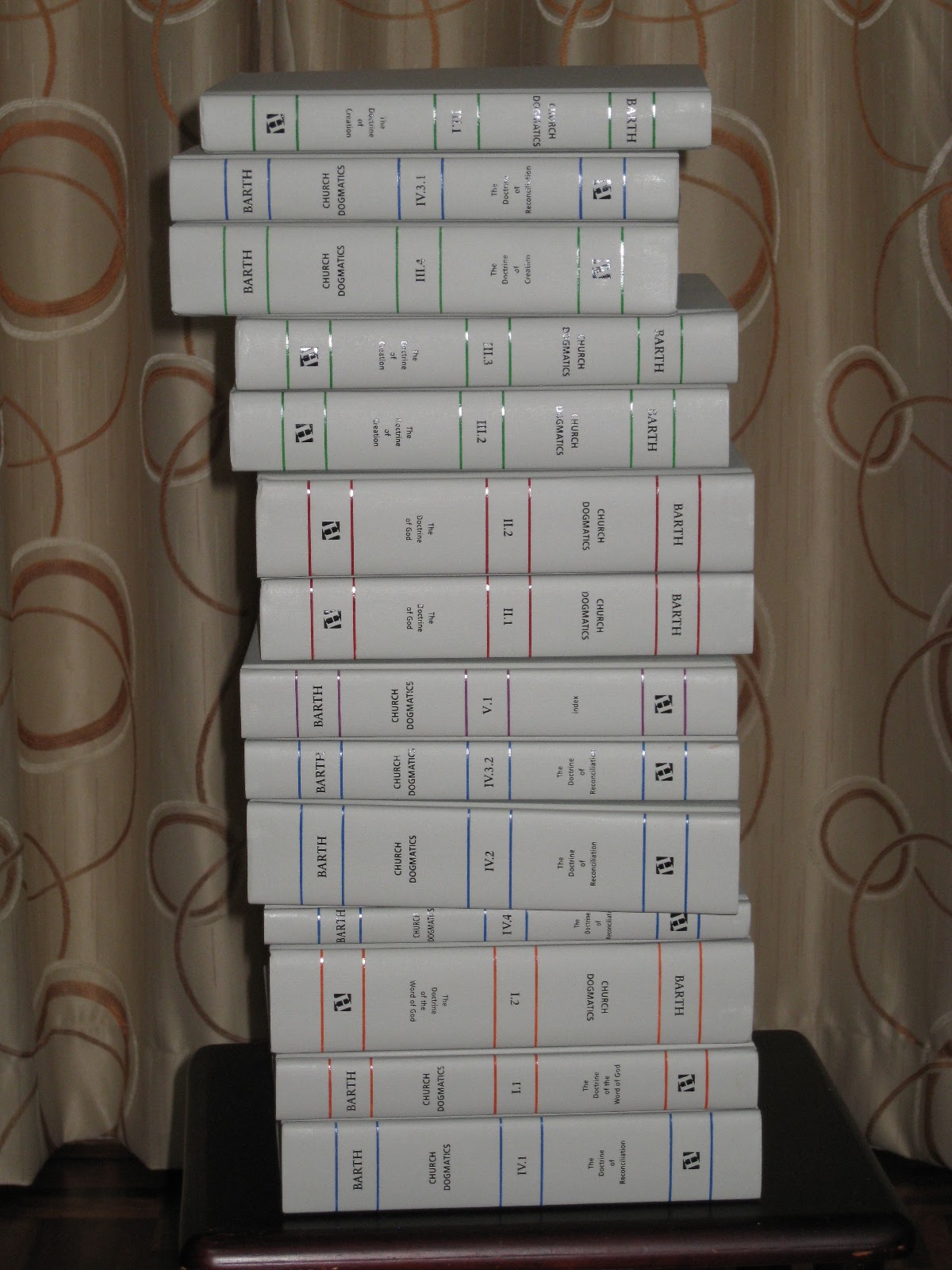

Fritz Barth died on February 25, 1912. Karl Barth’s father, himself a theology professor, was only fifty-five. Among his last words were:

Fritz Barth died on February 25, 1912. Karl Barth’s father, himself a theology professor, was only fifty-five. Among his last words were: