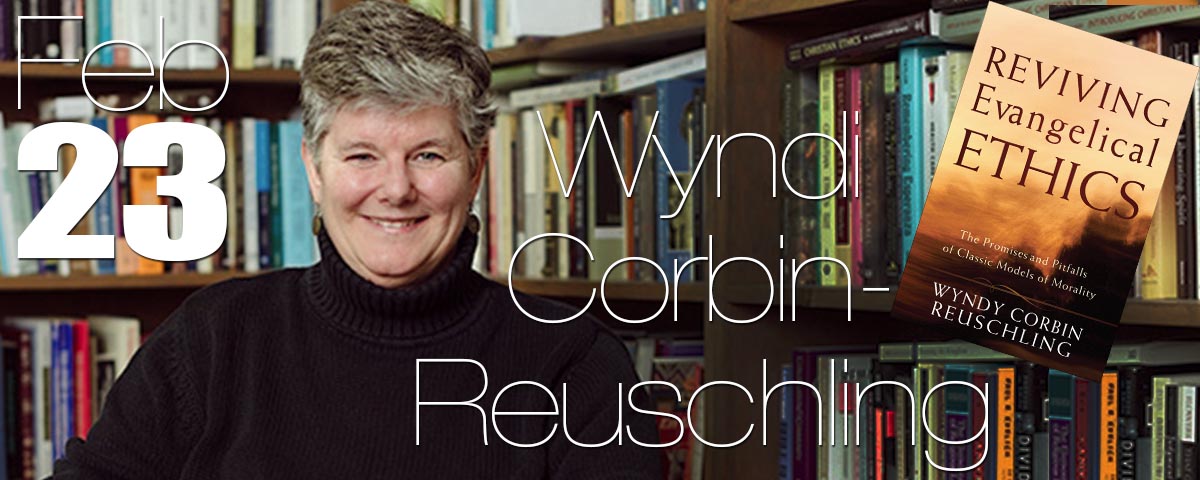

This semester I have been teaching an introductory unit in Christian ethics and for my undergraduate students, assigned Wyndy Corbin Reuschling’s Reviving Evangelical Ethics as a text. I also required a report on the book to ensure students actually read it! Previously, I have assigned Arthur Holmes’ Approaching Moral Decisions, which is also a good book. Nevertheless, I found Holmes a little conservative and dated in some respects, and felt that Corbin Reuschling had a good contribution to make to the subject. I also want to include some women in my reading lists where an appropriate text is available, to help even up the voices that students are reading and listening to.

This semester I have been teaching an introductory unit in Christian ethics and for my undergraduate students, assigned Wyndy Corbin Reuschling’s Reviving Evangelical Ethics as a text. I also required a report on the book to ensure students actually read it! Previously, I have assigned Arthur Holmes’ Approaching Moral Decisions, which is also a good book. Nevertheless, I found Holmes a little conservative and dated in some respects, and felt that Corbin Reuschling had a good contribution to make to the subject. I also want to include some women in my reading lists where an appropriate text is available, to help even up the voices that students are reading and listening to.

Wyndy Corbin Reuschling writes as an evangelical concerned that evangelicals have thinned out their moral reflection, as well as the moral nature of Christian salvation and life because of historical commitments to patterns of piety, and modern commitments to cultural priorities such as pragmatism, personal fulfilment, and ecclesiastical success. Corbin Reuschling surveys the three classic models of ethical reflection—deontology, teleology and virtue ethics—via a discussion of major theorists in each field—Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill and Aristotle. She then explores in quite broad terms how a central aspect of each of these classic models finds expression in evangelical spirituality. The subtle shift from ethics to spirituality is not made overtly, but is probably intentional, and highlights Corbin Reuschling’s conviction that evangelicalism has a “thin” ethics. Thus she insists that spiritual formation is moral formation, and that one cannot be transformed into the image of Christ without an accompanying commitment to the moral and ethical concerns of Jesus.[1] In this vein, she associates deontology with evangelical biblicism, virtue with therapeutic forms of piety, and suggests that evangelical pragmatism might be considered as a kind of “spiritual utilitarianism.” In the final chapter she presents her own constructive proposal in terms of the development of a robust moral conscience, supported by robust Christian community, and a developed competence based in practical wisdom.

Corbin Reuschling begins by distinguishing between an “antecedent” conscience, an idea more at home in Roman Catholic moral philosophy, and a “consequent” or “judicial” conscience, more familiar in Protestantism. An antecedent conscience is simply a conscience developed prior to the ethical moment when one is faced with a dilemma, a choice, or some other ethical challenge. Corbin Reuschling defines conscience as follows:

Conscience is the active integration and use of our abilities to assess moral issues with our passionate moral commitments that reflect the heart of God’s justice with practiced determination to live and act according to our moral convictions. … This begs the necessity for the formation of an “antecedent conscience,” which Charles Curran describes as the capacities and sensitivities we need prior to an action to guide and direct our decisions in order to act according to the orientation that our moral values and sense of goodness give us.[2]

Later in the chapter she also approves van der Ven’s definition of conscience as “considered conviction … developed in and through sustained processes of thought, reflection, discovery, prayer, and dialogue.”[3] Clearly, such a conscience is not innate but rather must be formed. Nor is it private, because one’s conscience is socially mediated. The formation of robust Christian conscience, therefore, requires:

I. A deep and continuing immersion in and reflection on Scripture in order to,

- Confront each person and the community with the reality of evil in ourselves and in the world;

- Illuminate and motivate us with a renewed moral vision including the church as an alternative community, Christ and his cross as our essential paradigm, and the vision of the kingdom of God as our goal;

- Discover rich sources of moral wisdom, especially in the biblical narratives.

II. A community where these narratives are taught, where conscience is formed, where identity is narratively constructed, and where moral discourse and deliberation are encouraged and practised.

III. Skills of practical wisdom (phronesis) leading to moral competence. Practical wisdom includes the skills by which we move from the abstract to the particular, from the conceptual to the concrete, aware of the unique, contingent and open-ended nature of every moral situation. Practical wisdom is the application of “considered convictions” to this particular situation. It involves making moral judgements with reference to norms and values. It takes personal and corporate agency and responsibility seriously, with respect to this

By recovering the idea of conscience and situating its formation and use within the community, Corbin Reuschling retains the sense that each moral agent bears responsibility for their own decisions and actions, without privatising the moral life or to modern evangelical individualism. This unique balancing of the personal and the communal is a significant contribution.

Much more could be said about the book. By and large my students appreciated her moral vision, and the rigor she brought to the study. This, perhaps, is the best commendation I can give the book: they have suggested that I use it again next time I teach the unit.

[1] Wyndy Corbin Reuschling, Reviving Evangelical Ethics: The Promises and Pitfalls of Classic Models of Morality (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2008), 124.

[2] Ibid., 149, original emphasis.

[3] Ibid., 163-164.

An interesting article in Christianity Today by Timothy Dalrymple, president and CEO of the organisation. The article, “The Splintering of the Evangelical Soul,” is a diagnostic-explanatory account of why,

An interesting article in Christianity Today by Timothy Dalrymple, president and CEO of the organisation. The article, “The Splintering of the Evangelical Soul,” is a diagnostic-explanatory account of why, Mark Galli entitles his recent book on Karl Barth an ‘introductory biography for evangelicals.’ As a biography it is a faithful though simplified rendering of the broader and deeper story found in Eberhard Busch’s Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts (1976), upon which it draws heavily. With respect to his intended audience, Galli is writing specifically for evangelical Christians, not as a Barth specialist, but as an appreciative student and fellow-traveller.

Mark Galli entitles his recent book on Karl Barth an ‘introductory biography for evangelicals.’ As a biography it is a faithful though simplified rendering of the broader and deeper story found in Eberhard Busch’s Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts (1976), upon which it draws heavily. With respect to his intended audience, Galli is writing specifically for evangelical Christians, not as a Barth specialist, but as an appreciative student and fellow-traveller.