According to Hughes Oliphant Old, Karl Barth’s “Bremen” sermon was “one of the outstanding sermons of the twentieth century” (The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church, vol. 6, The Modern Age 1789-1989, 776, cited in Johanson, The Word in the World: Two Sermons by Karl Barth, 25).

According to Hughes Oliphant Old, Karl Barth’s “Bremen” sermon was “one of the outstanding sermons of the twentieth century” (The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church, vol. 6, The Modern Age 1789-1989, 776, cited in Johanson, The Word in the World: Two Sermons by Karl Barth, 25).

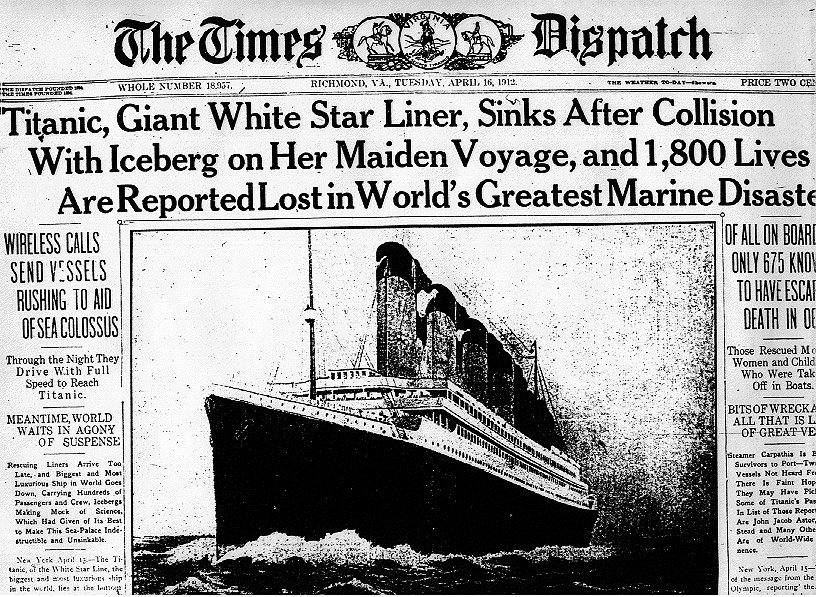

This sermon, from November 1934, was given when Barth was forty-eight years of age, and shortly before his expulsion from Germany by the National Socialists. The Nazis had seized control of the German nation, were interfering in the life of the church, and seeking to gain a totalitarian control over all the affairs of the nation. Although Hitler and the Nazis are never mentioned directly—Barth does not allow them to intrude into the sermon—they are in the background especially as the “Jesus of our pious imagination.” The sermon is clearly addressed to the congregation living “in these days and times” of great temptation and struggle, urging them to courageous obedience to the lordship of Jesus.

The sermon begins without fanfare, introduction, comment about context, etc.:

“Jesus made his disciples—which means, Jesus compelled his disciples—to get into the boat and go before him to the other side.” He made them, he compelled them to go their own way without him, while he was somewhere else. They probably didn’t understand what he wanted of them. It probably wasn’t what they wanted. But that was of no consequence for them: they allowed what they were told to be right for them and they did it; they obeyed. And this already tells us something decisive about ourselves, who are Jesus’ disciples, his church. This tells us that the church of Jesus Christ is the place where there is a bond which regulates human activity, a bond which cannot be debated over, which we have not chosen for ourselves, and from which we cannot release ourselves, but on the other hand a bond in which we also have the security and consolation which enable us to go on our own way as we should. Disciples of Jesus are people who are answerable to Jesus, and precisely for that reason answerable to no one else, people who are entirely bound, and precisely for that reason and in that bond, free people (Johanson, 46).

And so the sermon proceeds as a line-by-line exposition of the biblical text from Matthew 14. The text itself is front and centre, rather than various points abstracted from the text. Yet the exposition is not “historical” but applied as though the text speaks directly as “our story.” Barth provides a theological and ecclesial interpretation of the text. Thus the solitary Jesus of the story indicates that he “alone” is unique and sovereign; there can be no other sovereignty in competition with him. All other supposed sovereigns are “ghosts,”—fakes, yet still capable of being a destructive power in the world. There is no prize for guessing what Barth is saying here!

In Barth’s hands, Peter is the Confessing Church, boldly stepping out in obedience to Jesus, but fearful and faltering—and also helped! Is Peter’s request to walk on the water the result of pride (Calvin) or serious faith? Barth refuses to commit himself to an answer here, but says:

What is required—what Jesus Christ continually requires—are rocks like this who are certainly not perfectly untainted people, who are perhaps seriously objectionable in many ways and will have much to answer for, but are nevertheless ready to do something quite specific, to render obedience to a specific word by undertaking a specific service. In the church of Jesus Christ there is not only waiting, there must also be those individuals who are continually hastening, watching, rising where they are called to, with all the perils that entails. The church could not do without them, and the church cannot do without them today either. And now in this hour, the text puts this question to each and every one of us: And you, are you not also called to obey in a specific way? To be sure, we must examine ourselves to see whether we are ready to obey the orders of Jesus Christ, or whether the appeal we are now hearing might not come from some chimera within our hearts. But equally, let us examine ourselves to see whether it is not the result of our cowardice and unbelief if we not assume this specific task, this specific act of obedience to which we are summoned! (55)

It is hard to imagine a more forthright summons to the church assailed by Hitler’s regime, yet this is precisely how Barth is applying the biblical text. Just as Peter by his action was distinguished from the other disciples,

There is distinction like this in the church; people who are distinguished by what is demanded of them, distinguished by the dangers to which they expose themselves, but also distinguished by the help that comes their way. And distinction like this, a specific event like this, has always been the mystery of the great periods of the Christian church. Is it the case that distinction like this is to be granted to us too in these days and years, to us, to our evangelical church, in that from the midst of everything that bears the name of church, a crowd has dared to step out in obedience and become the confessing church? (56)

Barth finds in Peter’s example “the history of every great event in the church” (58). Peter has heard the word of Jesus but looks also at the storm, the wind, and the waves. Now it is no longer a matter simply of Jesus and his word, but of the storm, “of practical and strategic matters, of oneself and one’s desires and crises” (56). But even Peter’s little faith did not forfeit the faithfulness of God toward him. In the dark years that followed this sermon there is no doubt that many in this congregation would have been seriously confronted with the force of this dilemma: will I respond to the sole lordship of Jesus Christ—at great personal cost, or will I falter and look away, trying both to obey Jesus’ command to rise and walk, and to stay in the safety of the boat.

How, though, can we be sure that we are hearing his voice, his command, his encouragement—“is it him, or is it the illusion of our hearts?” (56). Discernment in the time of decision is often unclear and even fraught. But we must risk obedience and act. We do wait; we must hasten! And Christ is with us. How may we distinguish the command of Christ from the deceitful or frightened desire of our own hearts?

And if you say to me, “Indeed, but isn’t there always still room for error; couldn’t the voice of our own hearts always try to pass itself off as the voice of Jesus Christ?” then my reply is, “We may and must continually seek the word, the conclusive word of Jesus Christ himself, in the word to which the prophets and apostles are witnesses, the word of those who for every age have born testimony to him, to his revelation, to his work, to the love of God which has appeared in him.” And whoever hears this testimony to him knows that he himself is there, that the light is there, the truth is there, the victory is there; not a human victory but God’s victory in his church, even in such times of tribulation and division as we are now living through. We can be sure that the victory is always on the side of the Holy Scripture, and so it is today (53).