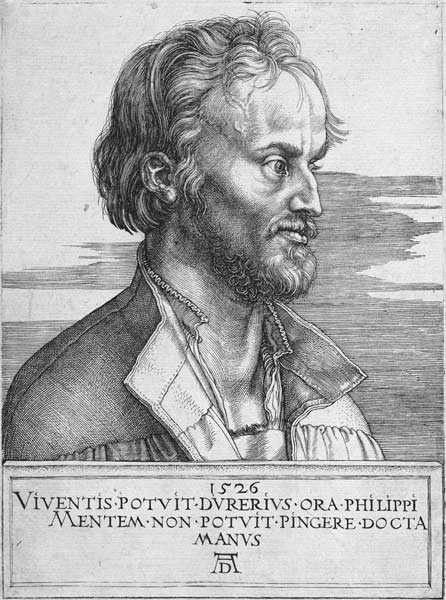

Scott Hendrix, Emeritus Professor of Reformation History at Princeton Theological Seminary, has written an articulate, detailed and highly readable story of the remarkable life of Martin Luther. Subtitled Visionary Reformer, we catch a glimpse of Hendrix’s purpose on page 115:

Scott Hendrix, Emeritus Professor of Reformation History at Princeton Theological Seminary, has written an articulate, detailed and highly readable story of the remarkable life of Martin Luther. Subtitled Visionary Reformer, we catch a glimpse of Hendrix’s purpose on page 115:

From this point on, freedom for Luther meant living bound to Christ, and that freedom made him much more than a protester against indulgences or a critic of the pope. Now he was a man with a larger vision of what religion could be and a mission to realize that vision by making other people free. The decisive turning point in his life was not the ninety-five theses or the Diet of Worms. It happened at the Wartburg, where he adopted a new identity and a new purpose that he believed to have come from God. It was based on a vision of what Christianity could become – a vision he was intent on pursuing.

Hendrix has divided his book into two parts. Part one, “Pathways to Reform,” covers the period 1483–1521, while part two, “Pursuit of a Vision” treats 1522–1546. The first part consists of eight chapters that introduce Luther and set him firmly in the context of late medieval Germany. Hendrix’s Luther is very much a normal (sixteenth-century) man, “neither a hero nor a villain, but a human being with both merits and faults” (xi). Drawing on a lifetime of learning, and extensively referencing German, Latin, and English-language sources, Hendrix rejects the “popular version” of the “cliché” or “myth of Luther the hero” (33, 39). Luther did join the monastery against his father’s wishes but whether solely as a result of the storm is doubtful. Although we know he posted his ninety-five theses to Archbishop Albert of Mainz, we cannot be quite as certain that he posted them on the doors of Castle Church. He was not a solitary or isolated figure, but embedded in communities and friendships which functioned as networks of support during the Reformation. Although he did struggle with his conscience, his psychological state must not be over-emphasised. His theological breakthrough was not simply the result of a monk’s desperate search for a gracious God, but also many years of intellectual and academic development, accompanied with pastoral reflection.

Hendrix details Luther’s demanding schedule in the years prior to 1517 as a cleric, professor and administrator. “When the ninety-five theses made their splash, their author was not an insignificant Augustinian monk. Rather, Brother Martin belonged to the senior management of the Reformed Congregation” (46). His initial aim was reform of the curriculum at Wittenberg University, along humanist rather than scholastic lines, emphasising the study of Scripture and the early teachers of the church, especially Augustine. But the indulgence controversy caused the reforming impulse to move beyond the university. Here a pastoral motive emerges alongside the theological; this was theology applied for the nature of the gospel and the salvation of the people was at stake. Thus theological, pastoral, hermeneutical—and financial and political—factors combined to spark the Reformation.

Although by 1517 Luther was “pushing reform on two fronts: academic theology and popular piety” (68), he was not yet the “visionary Reformer” he later became. His disputations at Heidelberg, and with Cajetan and Eck were apologetic attempts to commend his new theology. Only in 1520 did he “turn a corner,” believing that the time had come to “speak out” (89). By now he had given up on the clergy taking up the call to reform the church, and so turned to the German nobility to reform the practice of religion in Christendom. The papal bull Exsurge Domine, the edict of ex-communication, and the summons to appear before the emperor at Worms issued in Luther’s determination to recognise the authority of scripture as greater than that of the papacy. Cast out of the church, released from his monastic vows, officially an outlaw, and in hiding for his life, Luther faced, to put it mildly, an uncertain future which neither he nor his friends nor his protector could fathom (112-113). It was in this liminal space, suggests Hendrix, holed up in the Wartburg, that Luther became then a man possessed of a new identity, vision and purpose, a “visionary Reformer.”