Mark’s Passion Narrative (8)

They went to a place called Gethsemane;

and he said to his disciples, ‘Sit here while I pray.’

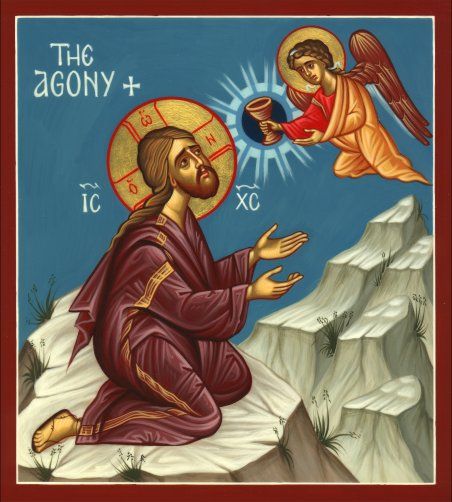

Situated on the Mount of Olives, Gethsemane means ‘olive press.’ The gospel writers don’t appear to make anything of this, at least explicitly, but the Christian tradition has. Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane is described as his ‘agony’ in the Garden, as in this accompanying icon from the Orthodox churches. The reference is from Luke’s account: “And being in agony [agõnia] He was praying very fervently; and His sweat became like drops of blood, falling down upon the ground” (22:44). Agõnia, properly speaking, is the mindset of an athlete preparing for the contest. Here it signifies agony or dread (Zerwick & Grosvenor, A Grammatical Analysis of the Greek New Testament, 273). The word is also used by Paul when he describes his struggle, his ‘hard labour,’ and striving in prayer for the believers in that city (Colossians 1:29-2:1). When he was in Jerusalem, at least in the final week of his life, Jesus made a practice of withdrawing to this garden to spend the evenings there (Luke 21:37), presumably in prayer. The olive is being crushed, smashed, pressed, such that its ‘blood,’ its oil is being poured out. Jesus’ passion is already in play. You can read Mark’s account of the agony in Gethsemane here.

Situated on the Mount of Olives, Gethsemane means ‘olive press.’ The gospel writers don’t appear to make anything of this, at least explicitly, but the Christian tradition has. Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane is described as his ‘agony’ in the Garden, as in this accompanying icon from the Orthodox churches. The reference is from Luke’s account: “And being in agony [agõnia] He was praying very fervently; and His sweat became like drops of blood, falling down upon the ground” (22:44). Agõnia, properly speaking, is the mindset of an athlete preparing for the contest. Here it signifies agony or dread (Zerwick & Grosvenor, A Grammatical Analysis of the Greek New Testament, 273). The word is also used by Paul when he describes his struggle, his ‘hard labour,’ and striving in prayer for the believers in that city (Colossians 1:29-2:1). When he was in Jerusalem, at least in the final week of his life, Jesus made a practice of withdrawing to this garden to spend the evenings there (Luke 21:37), presumably in prayer. The olive is being crushed, smashed, pressed, such that its ‘blood,’ its oil is being poured out. Jesus’ passion is already in play. You can read Mark’s account of the agony in Gethsemane here.

As Jesus comes to pray, he divides his disciples into two groups, saying to the first, “Sit here until I have prayed.” Surprisingly, he doesn’t ask them to pray. But going further, he takes three disciples: Peter, James, and John. These three have been Jesus’ close companions on other occasions. They were amongst the first called and chosen by Jesus as disciples (1:16-20). They have seen Jesus’ glory: on the Mount of Transfiguration (9:2) and in his act of raising Jairus’ daughter from the dead (5:37). But Mark also shows them failing to understand the nature of Jesus’ mission, despite their closeness to him (cf. 8:32-35; 9:38-41; 10:35-41).

Jesus begins to be “very distressed and troubled,” sharing with his three friends, “My soul is deeply grieved to the point of death; remain here and keep watch.” The nature of Jesus’ anguish is likely emotional, psychological, and spiritual. He is aware of his impending fate and naturally recoils from it. Grief, heartache, and anguish have taken hold of him, as he suffers that which afflicts almost all people when confronted with their own, imminent death.

That Jesus intends the three disciples to pray with him is indicated clearly in verses 37-38: “Could you not keep watch for one hour? Keep watching and praying…” Jesus seeks the prayerful support of his friends, their companionship in his hour of need, their presence and their prayer. This is true even as he goes on still a little further to pray alone. Jesus falls to the ground, perhaps overwhelmed though also in a posture of prayer. Mark gives us the content of Jesus’ prayer: he begins by asking that “if it were possible, the hour might pass Him by” (Mark 14:35).

Here we see Jesus in the fulness of his humanity. Here, a cry for deliverance and escape. Here a cry from the heart, the will of Jesus for something different, something else, something other than this fate; he prays that ‘this hour’ might pass him by. Here Jesus enters even more deeply into human existence and human experience. Nowhere in the gospels is Jesus’ true humanity more evident than in this passage. His existence is a truly human existence. He shrinks from suffering and death. He does not will these things. He longs for friendship, companionship, and support; he cries out for divine deliverance. As human he cries out for God’s help, for God to do what he cannot do.

And yet, Jesus has come to Jerusalem: he need not have done so. And he need not stay. Even now, he could take to his heels and remove himself—he still has agency. But there is also a sense of divine ordination at play. Jesus is aware of the cup he must drink, and though he shrinks from it and wonders if perhaps God might have another possibility, he does not withdraw. Instead, he bows, he submits. And in this, we see also Jesus in closest intimacy with his father:

And He was saying, “Abba, Father, for you all things are possible; remove this cup from me; yet, not what I want, but what you want” (Mark 14:35-36).

Jesus does not will suffering and death, but he does will the Father’s will, and so accepts the suffering and death. Humanly, he wills one thing; but there is a deeper will breaking in and breaking through. There is a mystery of divine and human willing here, and the earlier stories told by Mark of Jesus’ baptism (1:9-11) and transfiguration (9:2-8) provide the necessary insight required to understand it—as best we can. Jesus is truly human though in a way utterly unique. Jesus is truly human but not merely human. There is an inner reality to his being and existence, even in Mark’s gospel, though more clearly portrayed in the other gospels. He is the ‘Incarnate,’ the eternal Son-become-flesh, God with us (cf Matthew 1:22-23; John 1:1, 14).

The eternal Son of God has clothed himself in flesh and is now also the Human Son. The Human Son cries for deliverance but Jesus is also and more deeply the Eternal Son who is one with the Father. The eternal will of God the Father is also that of the Eternal Son, and it is this will which prevails in the life of Jesus. The deeper will leads and as Jesus ‘agonises’ in prayer, as he wrestles and strives, the will of the Human Son finally accepts the suffering and death which, although alien to the divine being—God does not suffer and die!—is not foreign to the Incarnate.

In the mystery of his divine Sonship, Jesus submits—as human—to the will of the Father, accepting what humanly, he does not will. In the mystery of his human Sonship, Jesus obeys—in and through the grace of his eternal being—the Father’s will for his human existence.

Jesus prayed “remove this cup from me.” Yet this is the cup which is the blood of the Covenant poured out for many (14:23-24), poured out for us, for you, for me, “for us and our salvation.”

“Yet not what I will, but what You will.”