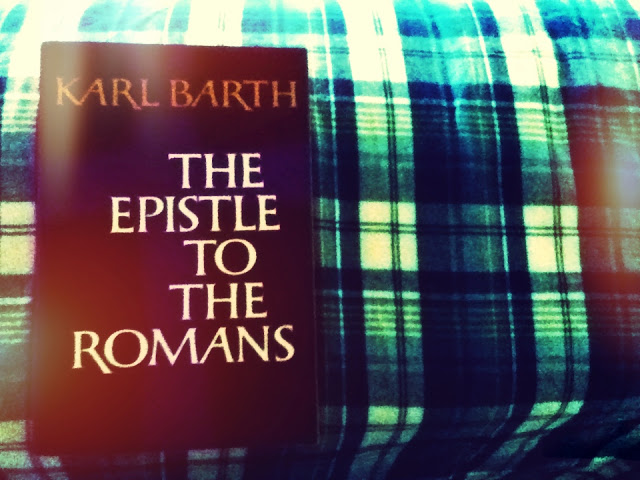

The Karl Barth Study Group met at ANZATS for the third time, this year in Adelaide. We chose a theme for the papers this year: “Reading Romans with Barth,” in view of the upcoming centenary of the first edition of Barth’s commentary on Paul’s epistle. Although four papers were scheduled, one presenter had to withdraw due to family medical concerns. However, the remaining papers were each interesting and well received, and good interaction and discussion followed the presentations.

The first paper given by Chris Swann, a doctoral candidate at St Mark’s Theological Centre, addressed the topic “Discipleship beyond Taste & Taboo: Barth on Food & Freedom in Romans 14:1 – 15:7.” When I was doing my own work on these chapters in the second edition of Barth’s commentary I was disappointed, feeling that Barth had missed an opportunity to develop a strong theological description of relations in the Christian community. But Chris did a better job than I had with respect to Barth’s position. He recognises that Barth follows Paul by calling for the strong to sacrifice their liberty, and as such, insists that the divine krisis falls on weak and strong alike. Barth rejects all liberty as well as rigorism: all human positions are impure before God. But Chris showed that Barth’s position does indeed open into a thick description of a truly generous community ethic as we recognise and honour the One in the other.

Sean Winter, New Testament scholar at Pilgrim College in Melbourne, examined Romans 11:33-36, which is the climax of the first long section of Paul’s letter. Sean noted the utter forcefulness of Barth’s rhetoric in this section—a forcefulness attenuated in Hoskyns’ translation.

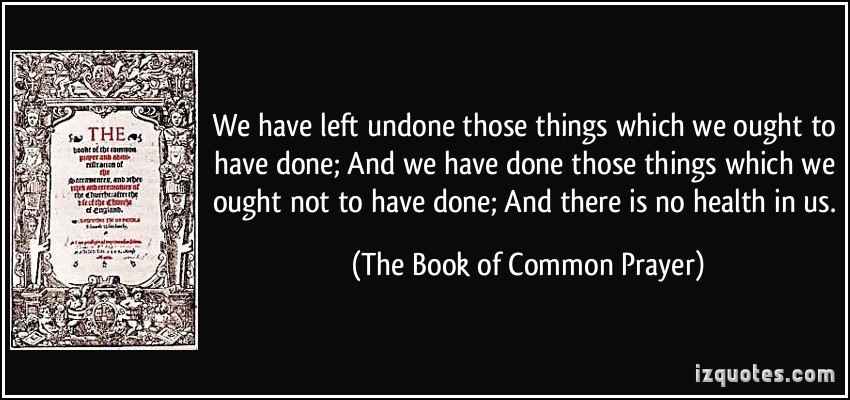

Direct knowledge of God? Nein! Cooperation with his dec isions? Nein! The possibility of holding him, or binding him, or obligating him, or ente3ring into a reciprocal relationship with him? Nein! No Federal theology. He is God, he himself, he alone. That is the ‘Ja’ of Romans.

God is known only in his inscrutability, clearly seen in his invisibility. God does not give himself over to us in his revelation but remains the utterly sovereign and hidden God.

My own paper examined Barth’s commentary in the first edition on Romans 5:12-14 where Barth addresses the question of Adam. In particular, I examined the curious translation of typos as Gegenbild, or ‘antitype.’ Is Barth playing fast and loose with the biblical text? Can we see in this translation an early indication of the theology which would come to expression later as a result of his doctrine of election in which Christ precedes Adam? I argued that the answer on both counts was No, and that in fact, Barth’s exegetical approach treated the biblical text very seriously and carefully, although also in accordance with his own hermeneutical stance which I picture as Barth standing alongside Paul looking at that to which Paul is pointing, seeking to see—in his own twentieth century context—what Paul could see, and to hear—in his own twentieth century context—what Paul could hear.

This year’s meeting of the Study Group fulfilled the purpose for which I started it three years ago. It was an encouraging and stimulating experience to meet with other scholars and explore something of Barth’s legacy. Perhaps we may even be able to do it again, next year!

This week I have been at the 2017 ANZATS Conference in Adelaide. The theme this year has been “Kinship & Family in Contemporary Australia and New Zealand.” The two international guests have given excellent plenary addresses, and the elective sessions that I have attended have been good. Of course, one of the best things about Conferences is catching up with peers from around the country—and from New Zealand, and meeting new friends.

This week I have been at the 2017 ANZATS Conference in Adelaide. The theme this year has been “Kinship & Family in Contemporary Australia and New Zealand.” The two international guests have given excellent plenary addresses, and the elective sessions that I have attended have been good. Of course, one of the best things about Conferences is catching up with peers from around the country—and from New Zealand, and meeting new friends.