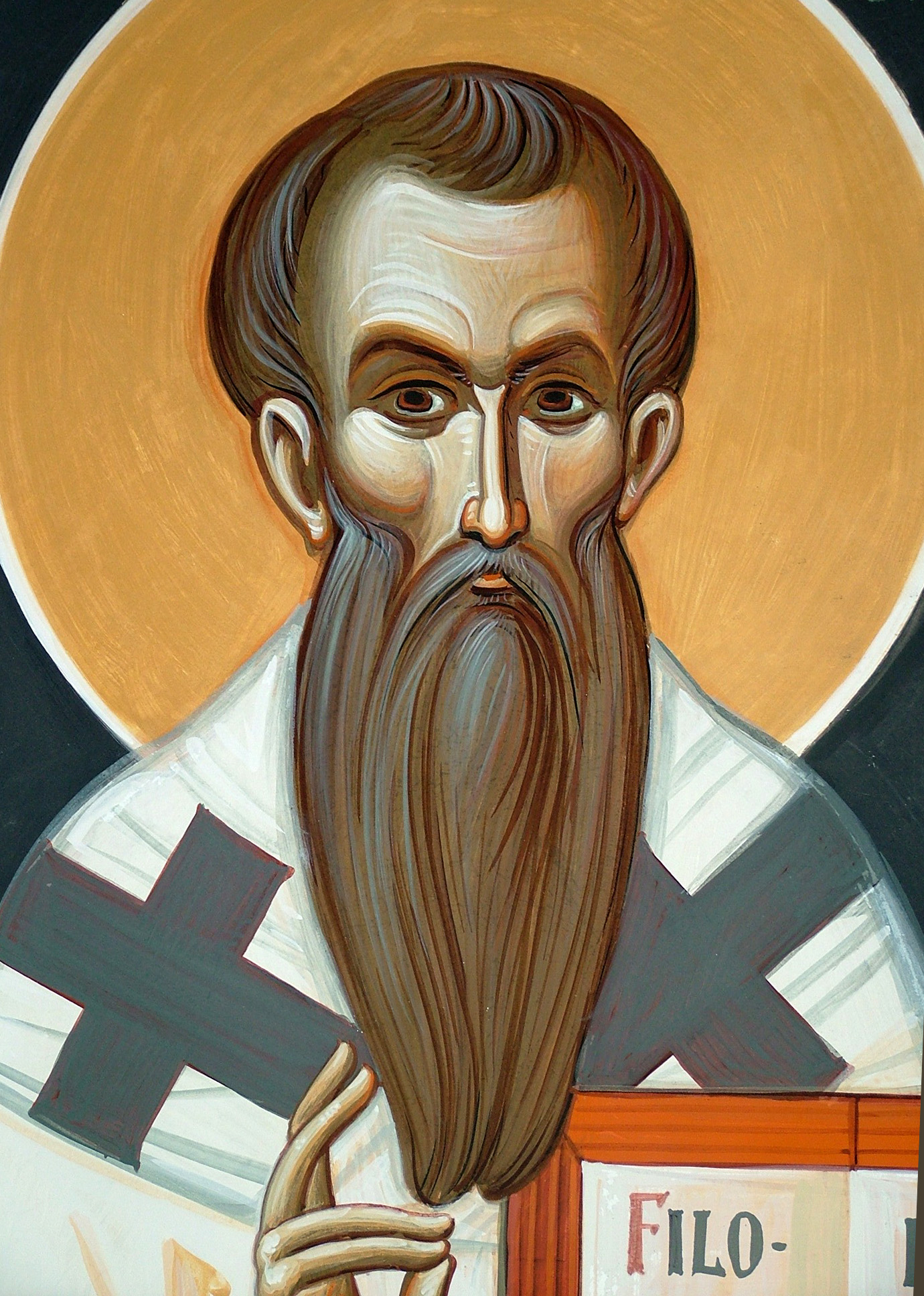

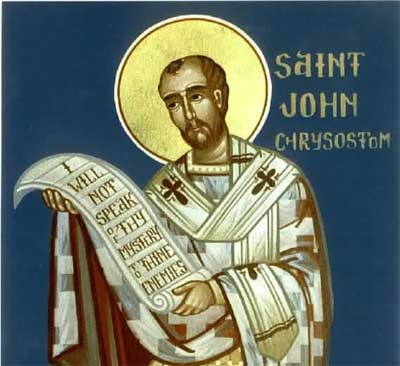

John Chrysostom (c. 349-407) was a celebrated preacher and archbishop of Constantinople in the ancient church. Chrysostom is a nick-name meaning “golden-mouth,” given to him on account of his eloquence. In this excerpt from a Christmas sermon we catch a glimpse of his oratory, but even more of his vision of Christ: his miraculous and marvellous birth, his deity and his humanity, his humility and exaltation, the victory of the cross and deliverance and exaltation of humanity: God is on earth and humanity in heaven!

John Chrysostom (c. 349-407) was a celebrated preacher and archbishop of Constantinople in the ancient church. Chrysostom is a nick-name meaning “golden-mouth,” given to him on account of his eloquence. In this excerpt from a Christmas sermon we catch a glimpse of his oratory, but even more of his vision of Christ: his miraculous and marvellous birth, his deity and his humanity, his humility and exaltation, the victory of the cross and deliverance and exaltation of humanity: God is on earth and humanity in heaven!

*****

Suddenly a great company of the heavenly host appeared with the angel, praising God and saying, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men on whom his favour rests” (Luke 2:13-14)

I behold a new and wondrous mystery. My ears resound to the shepherds’ song, piping no soft melody, but chanting forth a heavenly hymn. The angels sing. The archangels blend their voice in harmony. The cherubim hymn their joyful praise. The seraphim exalt his glory. All join to praise this holy feast, beholding the Godhead here on earth, and humanity in heaven. He who is above, now for our redemption dwells here below; and he that was lowly is by divine mercy raised up…

And ask not how: for where God wills, the order of nature yields. For he willed, he had the power, he descended, he redeemed; all things move in obedience to God. This day he who is, is born; and he who is, becomes what he was not. For when he was God, he became human; yet not departing from the Godhead that is his. Nor yet by any loss of divinity became he human, nor through increase became he God from being human; but being the Word he became flesh, his nature remaining unchanged…

What shall I say to you; what shall I tell you? I behold a mother who has brought forth new life; I see a child come to this light by birth. The manner of his conception I cannot comprehend. Nature here is overcome, the boundaries of the established order set aside, where God so wills. For not according to nature has this thing come to pass. Nature here has rested, while the will of God laboured. O, ineffable grace! The only begotten One, who is before all ages, who cannot be touched or perceived, who is simple, without body, has now put on my body, which is visible and liable to corruption. For what reason? That coming amongst us he may teach us, and teaching, lead us by the hand to the things that we mortals cannot see…

What shall I say! And how shall I describe this birth to you? For this wonder fills me with astonishment. The Ancient of Days has become an infant. He who sits upon the sublime and heavenly throne now lies in a manger. And he who cannot be touched, who is without complexity, incorporeal, now lies subject to human hands. He who has broken the bonds of sinners is now bound by an infant’s bands. But he has decreed that ignominy shall become honour, infamy be clothed with glory, and abject humiliation the measure of his goodness. For this he assumed my body, that I may become capable of his word; taking my flesh, he gives me his spirit; and so he bestowing and I receiving, he prepares for me the treasure of life. He takes my flesh to sanctify me; he gives me his Spirit, that he may save me.

Truly wondrous is the whole chronicle of the nativity. For this day the ancient slavery is ended, the devil confounded, the demons take flight, the power of death is broken. For this day paradise is unlocked, the curse is taken away, sin is removed, error driven out, truth has been brought back, the speech of kindliness diffused and spread on every side—a heavenly way of life implanted on the earth, angels communicate with people without fear, and now we hold speech with angels.

Why is this? Because God is now on earth, and humanity in heaven; on every side all things commingle. He has come on earth, while being fully in heaven; and while complete in heaven, he is without diminution on eaerth. Though he was God, he became human, not denying himself to be God. Though being the unchanging Word, he became flesh that he might dwell amongst us…