I have been enjoying Roger Olson’s The Journey of Modern Theology for the last few weeks. It has taken many, many hours so far and I am still 130 pages from the end. One thing that has struck me is how prominent the thought and influence of Hegel has been throughout the twentieth-century. At several points Olson refers to one or another theologian who has been influenced by, or sought to exorcise, Hegel’s “ghost.”

I have been enjoying Roger Olson’s The Journey of Modern Theology for the last few weeks. It has taken many, many hours so far and I am still 130 pages from the end. One thing that has struck me is how prominent the thought and influence of Hegel has been throughout the twentieth-century. At several points Olson refers to one or another theologian who has been influenced by, or sought to exorcise, Hegel’s “ghost.”

I have been accustomed to thinking of modern theology as deriving more from Schleiermacher and Ritschl, either accepting and extending their thought and approach, or alternatively, reacting against it. Olson’s account of the “journey” which is modern theology, suggests that twentieth-century theology owes much more to Hegel than I had previously acknowledged. In his discussion of Hans Küng, for example, Olson notes Küng’s debt to Hegel with respect to the doctrine of God (581-582):

In spite of large areas of disagreement with Hegel, who had also taught at Tübingen, Küng is clearly dazzled by the German philosopher’s overall vision of the dialectical unity of God and the world. …

In Hegel, God and the world—or God and humanity—are not “rolled into one.” Nevertheless, they are united in intrinsic, reciprocal unity-in-differentiation, so that Hegel’s God “is rarely described as a living, active person in an I-Thou relationship, but rather as a creatively present universal life and Spirit” (Küng, Theology for the Third Millennium, 133). …

At the same time, Küng found much to embrace in Hegel’s concept of God and God’s relationship to the world. In contrast to the all too static and otherworldly God of traditional theism, Hegel’s God is living, dynamic and capable of suffering, and it includes its antithesis in itself, rather than standing aloof from the world’s history.

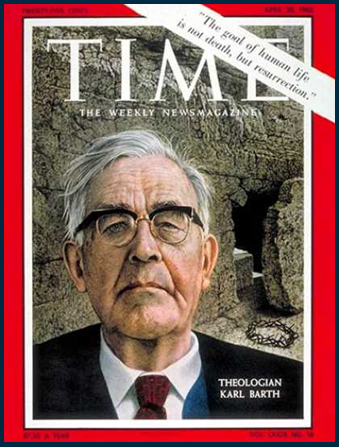

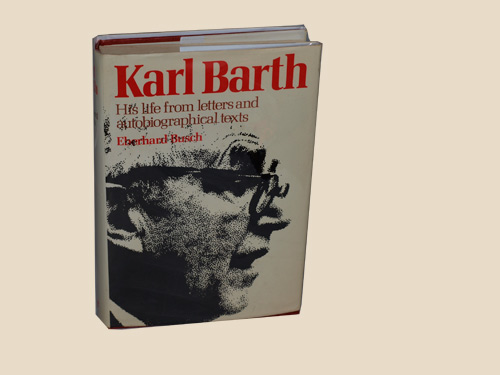

The historicisation of the divine being, the divine immanence and divine pathos: these are all the outgrowth of Hegel’s thought. Schleiermacher’s feeling of absolute dependence is a religious a priori which accounts for the shift in theological method which occurred in the nineteenth century, but Schleiermacher’s God was still utterly transcendent. True, it is a transcendence coupled with immanence: God is the “infinite, all-determining, supra-personal power immanent in everything” (144), but Hegel’s account of God deepened divine immanence, tying God necessarily to the historical process. God became dependent on the world for the realisation of his own being. In the twentieth-century, Barth developed the idea of a history in God, admittedly in very different directions to Hegel. Tillich, process thought, Moltmann and Pannenberg all echo Hegel in some aspect of their work.

Olson’s image of Hegel as a “ghost” is provocative, creative and stimulating—and probably quite true. It seems that we will be unable to understand twentieth-century theology without some understanding of Hegel.

Is that true of modern cultural sensibilities as a whole? Earlier this month our education minister, Christopher Pyne, walked away from the utilitarian views about postgraduate research he expressed while in opposition. Among his characterisations of “ridiculous” research projects was Hegelian philosophy. If Hegel’s ghost is as prominent in modern thought and culture as it has been in theology, there is nothing ridiculous in understanding him, even in cultural and secular contexts.