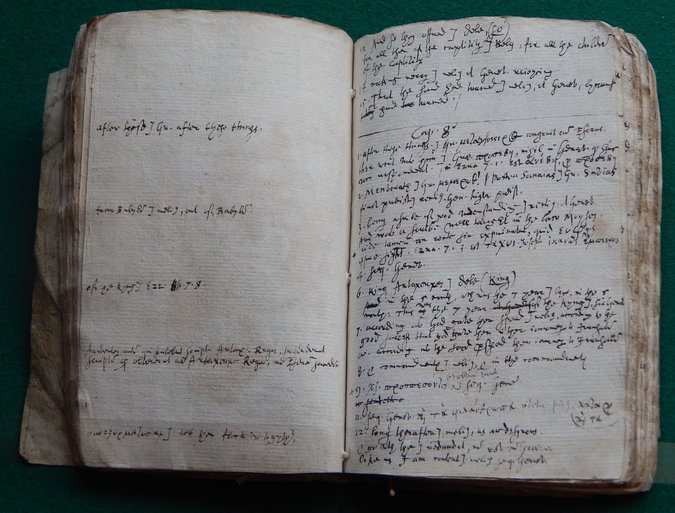

Felker Jones, Beth, Faithful: A Theology of Sex

(Ordinary Theology Series; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015), 108pp.

ISBN 9780310518273

In her new little book on sex, Beth Felker Jones, associate professor of theology at Wheaton College, Illinois, and author of The Marks of His Wounds: Gender Politics and Bodily Resurrection and Practicing Christian Doctrine: An Introduction to Thinking and Living Theologically, takes as her primary datum St. Paul’s declaration, “The body is for the Lord” (1 Corinthians 6:13):

In her new little book on sex, Beth Felker Jones, associate professor of theology at Wheaton College, Illinois, and author of The Marks of His Wounds: Gender Politics and Bodily Resurrection and Practicing Christian Doctrine: An Introduction to Thinking and Living Theologically, takes as her primary datum St. Paul’s declaration, “The body is for the Lord” (1 Corinthians 6:13):

Married or single, the body is one hundred percent for the Lord. … My hope is that we might move to a theology of the beautiful body, a theology of the sexual body, in which the body becomes—not an idol—but something like an icon. … Might the process of faithfully living in the body, including sexual discipline, be understood as something like the writing of an icon? (100-101)

In a litany of memorable one-liners scattered throughout the text, Jones declares that sex is (always) real, sex is good—though sex can also be bad, because sex has gone wrong; therefore sex must be freely given and freely received, because ultimately, for the Christian, at least, sex is kingdom work. Although part of Zondervan’s new Ordinary Theology series, this is anything but “ordinary theology.” Rather, it is a radical and often profound theology wonderfully packaged for the everyday reader and addressing an ordinary aspect of everyday reality. Actually, it is counter-cultural theology, robust and biblical, sensitive to the mystery of the wonder and brokenness that comprises human sexuality, deeply aware of the cultural and power dynamics that shape western culture, and attuned to the relational and personal dynamics which so deeply inform our sexuality and sexual practice.

In the first of her eight short chapters Felker Jones introduces her topic by arguing that to be human is to be embodied, and that what we do as embodied creatures, matters. Our existence in a larger reality means we are accountable within that larger reality for how we relate to others and use our bodies. “Sex matters because embodiment goes to the very heart of what it means to be human” (17). Thus, and radically in our cultural age, sex is about God, about who God is and how God relates to his creation. Sex is also about us and what it means to be truly human. Sex, then, is a witness to the faithfulness of God, and sexual ethics remain an essential aspect of Christian life.

Not only is (all) sex “real,” for Felker Jones, sex is also good. “The Christian faith is profoundly for the body and for the joys of the bodily life” (22). Therefore she rejects all forms of dualism and insists that God’s good creation intends our embodiedness and embodied relations, sexual differentiation, and marriage. “The one-flesh union of Eden—marked by commitment and mutuality and partnership and delight—is God’s good, creative, intention for sex” (38).

This created goodness has, however, been drastically impacted by the reality of human sinfulness. Sex has “gone wrong,” having been distorted in life under the conditions of sin. Despite the cultural difficulty of speaking about any kind of sex as “bad sex,” Felker Jones insists that,

We need the tools to discern when sex tells the truth about God and supports human flourishing and when sex denies the reality of God and is harmful to human beings. We must have a way to diagnose the situation we’re in, to know when we’re not embodying the truth of the God who is faithful. We need to be able to recognize when we’re embodying, instead, brokenness and idolatry and sin. (41)

Thus, “good sex” enables, creates, testifies to or delights in the three “goods” of sex: fidelity, fruitfulness, and the relationship of the husband and wife to God, whereas “fallen sex” is selfish, sex contrary to God’s good intentions, sex that exploits or denigrates, that is bought and sold, that preys on the nakedness of others, that is predatory, irresponsible, commodified or abusive (42-50). This is porneia, and the body is not for porneia but for the Lord.

In her fourth chapter Felker Jones applies the logic of death and resurrection to sex such that “pornication” is killed, and desire is reconstituted in ways that are equal, mutual, faithful and covenantal. Although sexual sin is pervasive and intensive it is not the end of the story. Redeemed sex has no place for commodification or exploitation of the other, but flourishes in a covenantal context of friendship and mutuality.

(Continued tomorrow…)

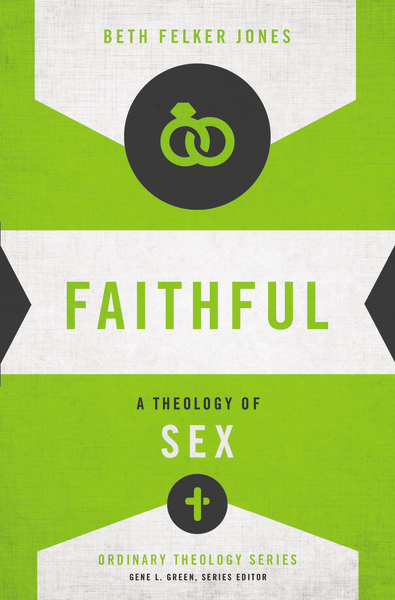

I love this epigram from Basil of Caesarea in his little letter to Eupaterius and his daughter, thought to have been written about 373. Basil here asserts the divinity of the Holy Spirit together with a rationale for it, in as brief a statement as I have ever seen:

I love this epigram from Basil of Caesarea in his little letter to Eupaterius and his daughter, thought to have been written about 373. Basil here asserts the divinity of the Holy Spirit together with a rationale for it, in as brief a statement as I have ever seen: