In my earlier post on Richard Rohr’s Falling Upwards I endeavoured to set forth sufficiently and sympathetically, the central tenets of his spiritual vision. It is a vision of ageing gracefully by finding a way—being led—to personal and spiritual maturity. The measures of this maturity are indicators such as being freed from the narrowness of self-serving ego needs, and of dualistic and exclusivist patterns of thought. The mature person has learnt to accept reality, and others, as they are, and have become more self-critical than critical of others. They have learnt that the secret of internal freedom and happiness is to ‘receive and return the loving gaze of God every day’ (159).

In my earlier post on Richard Rohr’s Falling Upwards I endeavoured to set forth sufficiently and sympathetically, the central tenets of his spiritual vision. It is a vision of ageing gracefully by finding a way—being led—to personal and spiritual maturity. The measures of this maturity are indicators such as being freed from the narrowness of self-serving ego needs, and of dualistic and exclusivist patterns of thought. The mature person has learnt to accept reality, and others, as they are, and have become more self-critical than critical of others. They have learnt that the secret of internal freedom and happiness is to ‘receive and return the loving gaze of God every day’ (159).

The book sets forth a range of perceptive insights and warnings that we do well to reflect upon. For example, Rohr insists that change and growth, movement and direction are integral aspects of a mature spirituality. Similarly, he warns that sin repressed or denied will surely break-out elsewhere. He wisely admonishes his readers toward practices of solitude and friendship, and reminds us that there is a connection between personal and spiritual maturity, and that we cannot ignore the one in the pursuit of the other. He speaks of the place of Jesus and of the church in his spiritual vision: ‘I quote Jesus because I still consider him to be the spiritual authority of the Western world, whether we follow him or not. . . . Jesus for me always clinches the deal, and I sometimes wonder why I did not listen to him in the first place’ (81).[1] The church he regards as ‘both my greatest intellectual and moral problem and my most consoling home’ (80). The church functions like a cauldron:

A crucible as you know, is a vessel that holds molten metal in one place long enough to be purified and clarified. Church membership requirements, church doctrine, and church morality force almost all issues to an inner boiling point, where you are forced to face important issues at a much deeper level to survive as a Catholic or a Christian, or even as a human. I think this is probably true of any religious community, if it is doing its job. Before the truth ‘sets you free,’ it tends to make you miserable (74).

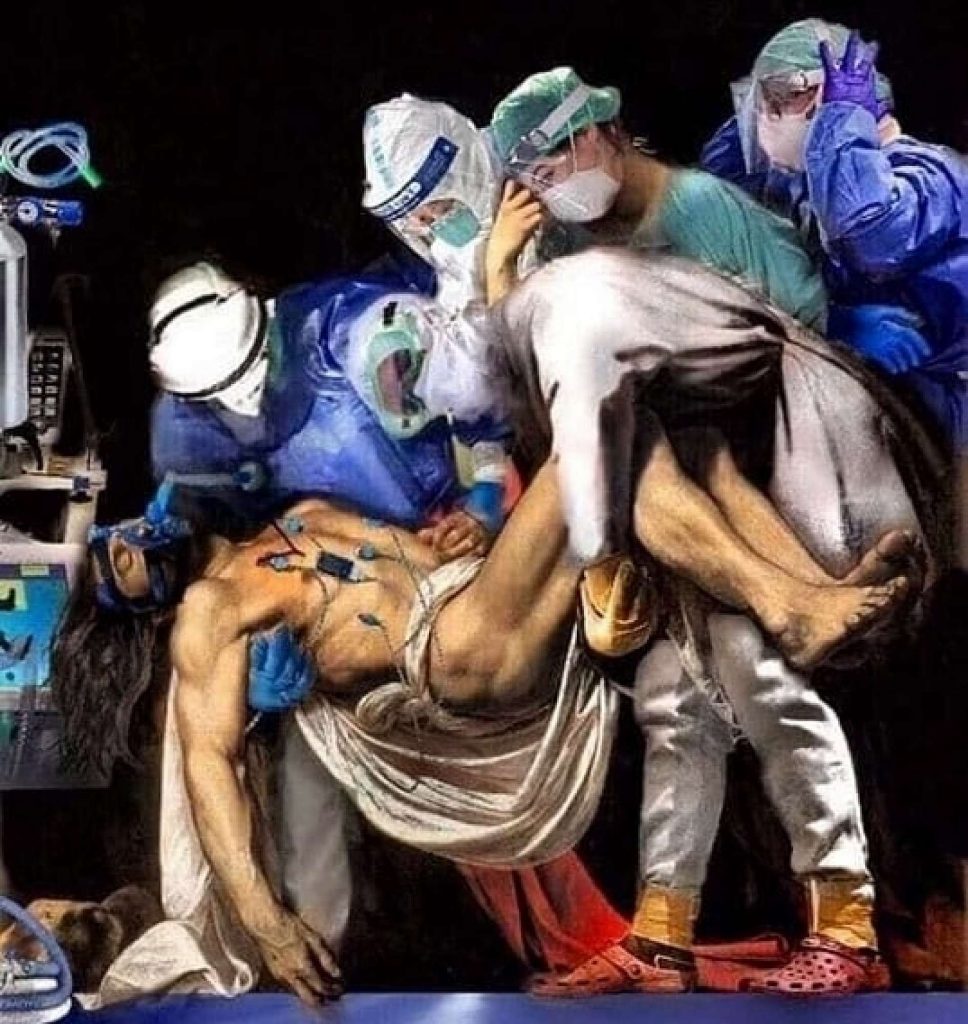

At the heart of his spiritual vision lies what he calls an ‘incarnational mysticism,’ a two-sided spirituality deeply grounded and engaged in the world and in ‘mystical union’ with God (75-78). It is incarnational as it is open to, inclusive of, and embracing the world in all its diversity, suffering, and beauty; mystical in its desire for immediacy, to abide in, as we have already noted, the loving gaze of God.

Despite the various strengths and claims of the book, I find I remain ambivalent toward this vision. Behind every exposition of spirituality lies a theological or philosophical vision of God and reality that in turn shapes the distinguishing features of the spirituality being proposed. As I understand it, Rohr’s theological vision is the product of a pluralist understanding of divine operations and revelation, and of human encounter with and participation in the divine. The spiritual quest is a universal impulse and Christianity is just one expression among many religious and non-religious quests for the truth. It is one expression of the primary spiritual insights which are found also in the writings of other religious leaders, poets, myth-makers, mystics, psychologists, and so on.

Despite the various strengths and claims of the book, I find I remain ambivalent toward this vision. Behind every exposition of spirituality lies a theological or philosophical vision of God and reality that in turn shapes the distinguishing features of the spirituality being proposed. As I understand it, Rohr’s theological vision is the product of a pluralist understanding of divine operations and revelation, and of human encounter with and participation in the divine. The spiritual quest is a universal impulse and Christianity is just one expression among many religious and non-religious quests for the truth. It is one expression of the primary spiritual insights which are found also in the writings of other religious leaders, poets, myth-makers, mystics, psychologists, and so on.

The portrayal of God in this book is remarkably thin and one-sided:

There is not one clear theology of God, Jesus or history presented, despite our attempt to pretend there is. The only consistent pattern I can find is that all the books of the Bible seem to agree that somehow God is with us and we are not alone. God and Jesus’ only job description is one of constant renewals of bad deals. The tragic sense of life is ironically not tragic at all, at least in the Big Picture. . . . Faith is simply to trust the real, and to trust that God is found within it—even before we change it (62-63).

The tactic applied here is not uncommon; find and emphasise the diversity of witness in the biblical documents and then use the fact of this diversity to discredit the reliability of the whole. This is lazy theology, though very convenient, for then one can introduce one’s own ‘reading’ as the explanation, or the meaning, or the key. In this case the knowledge we might have of God is stripped back almost to an empty abstraction. Is the gospel as vague and as bland as presented here—somehow God is with us and we are not alone? Is this really the extent of that for which we might hope? Is it the case that this ‘god’ exists merely to clean up our mess—and that we are those who will change the real? Somewhat ironically, just two pages earlier Rohr had complained that ‘organised religion has not been known for its inclusiveness or for being very comfortable with diversity’ (60). Although social diversity is an imperative, diversity in Scripture renders it questionable.

Rohr’s reading of Scripture and of the gospel thus appears somewhat reductionist, as he selects and emphasises only some aspects of the biblical-gospel narrative at the expense of other elements. His reading of the atonement, for example, is exemplarist and Girardian, and discounts the testimony and imagery of Paul, Peter, John, and Hebrews with respect to Jesus’ saving death on the cross (68-69). He interprets God’s forgiveness as a sign that ‘God is saying that God’s own rules do not matter as much as the relationship that God wants to create with us’ (56-57). It seems to me, however, that this is precisely the opposite of what the New Testament declares, that the very act of forgiveness, together with its necessity, presupposes that the ‘rules’ matter a great deal. In this respect Rohr’s position not only diminishes the New Testament portrayal of the cross of Jesus, but also treats the idea of sin—which surely includes the inhumanity and abuse of some towards others—as something negligible or easily dismissed. The Bible, on the other hand, approaches all kinds of sin with great seriousness.

Rohr argues for a spirituality based in ‘Big Picture incarnational mysticism.’ The Big Picture is a mechanism for side-stepping the particularities and details of a biblical vision in favour of a few generic universal principles. The image of the incarnation is employed with a dual purpose. On the one hand it affirms a spirituality of service amid the harsh realities of life in the world—something I also affirm. On the other hand, however, Rohr also uses it to affirm Western cultural priorities as though these are a religious obligation. This is cultural Christianity, something he otherwise rejects when it differs from his own cultural preference. Mystic desire or experience grounds the spirituality as a religious phenomenon without tying the adherent to any particular portrayal of God beyond the notion of God as absolute and unconditional love.

In the end Rohr’s spirituality appears as related variety of the ‘moralistic therapeutic deism’ that Christian Smith argued has become a major religious faith in North America. To me, this is not so much an exposition of Christian spirituality (and certainly not a biblical spirituality), as an exposition of a generic ‘spirituality’ suited perhaps for those who might claim to be ‘spiritual but not religious.’ This is a spirituality amenable for those who consider themselves ‘progressive’ whether religiously inclined or not. Richard Rohr himself is, of course, religious—he has been a Roman Catholic priest for most of his life, and finds his ‘most consoling home’ in the church. But he also admits that this is not a necessity per se. Other religious communities could just as easily assist and guide a person on their spiritual journey. I suspect, however, that some of his followers will not have the same degree of attachment to the church that he has, and may be led by this account of spirituality away from the God and the Jesus portrayed in Scripture, and into a spirituality and form of life of their own devising. Christians, whether Roman Catholics, Protestants, or disaffected evangelicals can do better much than this.

[1] It would be of interest, however, to assess Rohr’s understanding of Jesus in light of his more recent The Universal Christ (2019) in which he aims, according to one reviewer, to distinguish between Jesus and ‘Christ,’ with Jesus understood as limited, particular, and earthbound, while ‘Christ’ is unlimited, universal, and cosmic. I suspect that this move would allow him to displace the particularity of what Jesus actually says and does as recorded in the gospels, with an idiosyncratic content predicated upon his vision the universal Christ.