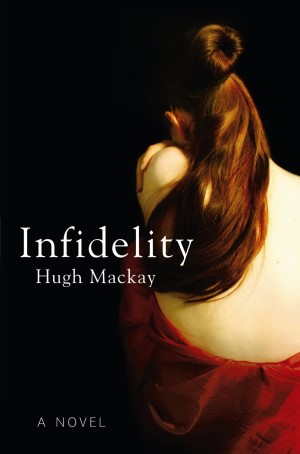

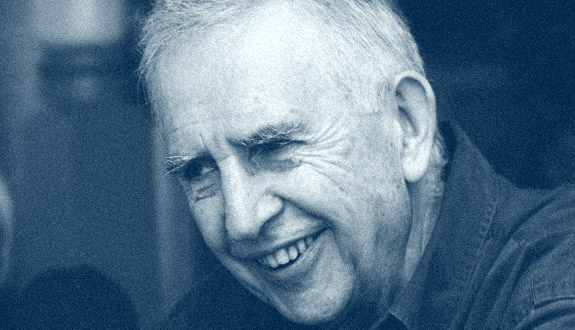

On Tuesday I gave a brief review of Hugh Mackay’s Infidelity. Here are a few more insights from the book, asides from Mackay the psychologist, which sparked an interest as I read. The first comes as Tom is discussing Sarah’s past with her mother, Elizabeth, and has relevance for the kinds of spirituality we nurture in the church, and especially in our youth and young adults groups. Elizabeth says of Sarah:

On Tuesday I gave a brief review of Hugh Mackay’s Infidelity. Here are a few more insights from the book, asides from Mackay the psychologist, which sparked an interest as I read. The first comes as Tom is discussing Sarah’s past with her mother, Elizabeth, and has relevance for the kinds of spirituality we nurture in the church, and especially in our youth and young adults groups. Elizabeth says of Sarah:

She went wild over religion, too. There was more than a bit of overlap, in fact. I think a lot of adolescents confuse spirituality and sexuality – don’t you, Tom? Or is it just that churchgoing covers all that steaminess in a cloak of respectability? (276)

The second finds Tom reflecting on the nature of intimate relationships, salient as a warning for all couples, and more broadly, for any kind of relationship:

I had heard plenty of clients describe the frightening lunge from ‘I love you’ to ‘I hate you.’ It had always struck me as being a bit like a passion hangover – when the stimulants were withdrawn, their toxic effects took over. The swing from devotion to indifference was more common, though, and more familiar to me. When the love switch is turned to ‘off,’ for any one of a thousand reasons, or none, the current simply stops flowing. You don’t have to hate someone to destroy a relationship – you just have to lose interest. (298)

The final thought comes from the final chapter of the book, and here Mackay’s agnosticism comes to the fore:

The hardest thing, finally, is to accept our insignificance in the scheme of things – or perhaps to accept that there is no ‘scheme of things.’ There are no inevitabilities. No embedded meanings, either – only those we choose to attach to what happens. And often, when we most ardently desire them, no answers. Life surges on, mostly out of control, rarely giving us respite… (310)

There is both wisdom and pathos in this statement. In the end, though, it seems that life, for Mackay, has only the meaning we ascribe to it. That we do ascribe meaning to life is part of what it means to be human. That we ascribe meaning to life, though natural, is also somewhat arbitrary and threatens to undermine the kind of ethics that Mackay wants to commend. This approach inevitably leads us back to ourselves as the moral centre in a manner reminiscent of the biblical book of Judges: “In those days there was no king in Israel; all the people did what was right in their own eyes” (Judges 21:25) – and the results were less than ideal. Stanley Grenz recognises this problem and argues that “justification of moral claims requires a foundational principle that in the end is religious” (The Moral Quest: Foundations of Christian Ethics, 58).

The message of the gospel is not that there are no inevitabilities, or that every question will be answered, or that life can be fully controlled. In these respects, Mackay is quite correct. Yet the gospel assures each person that their lives, choices and deeds can and do have enduring significance. Further, it testifies to a transcendent meaning embedded in the orders of creation and redemption that tells the truth of our existence and so provides an orientation to the good life. The moral life is not simply the assertion of power in this direction or that, but response to a transcendent reality which in the Christian tradition is understood in terms of the triune God of infinite goodness, holiness and love.