There is much in Luke 24 that we could speak about: Jesus’ resurrection and ascension, the discovery of the empty tomb by the women, the failure of the disciples to believe the women, the revelation of Jesus to the disciples at Emmaus, and so on. What I want to focus on particularly, however, is a hermeneutical move made by Jesus toward the end of the chapter.

There is much in Luke 24 that we could speak about: Jesus’ resurrection and ascension, the discovery of the empty tomb by the women, the failure of the disciples to believe the women, the revelation of Jesus to the disciples at Emmaus, and so on. What I want to focus on particularly, however, is a hermeneutical move made by Jesus toward the end of the chapter.

Now He said to them, “These are My words which I spoke to you while I was still with you, that all things which are written about Me in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms must be fulfilled.” Then He opened their minds to understand the Scriptures, and He said to them, “Thus it is written, that the Christ would suffer and rise again from the dead the third day, and that repentance for forgiveness of sins would be proclaimed in His name to all the nations, beginning from Jerusalem. You are witnesses of these things.

This text is an expansion of an earlier text in the chapter, where, with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus Jesus says:

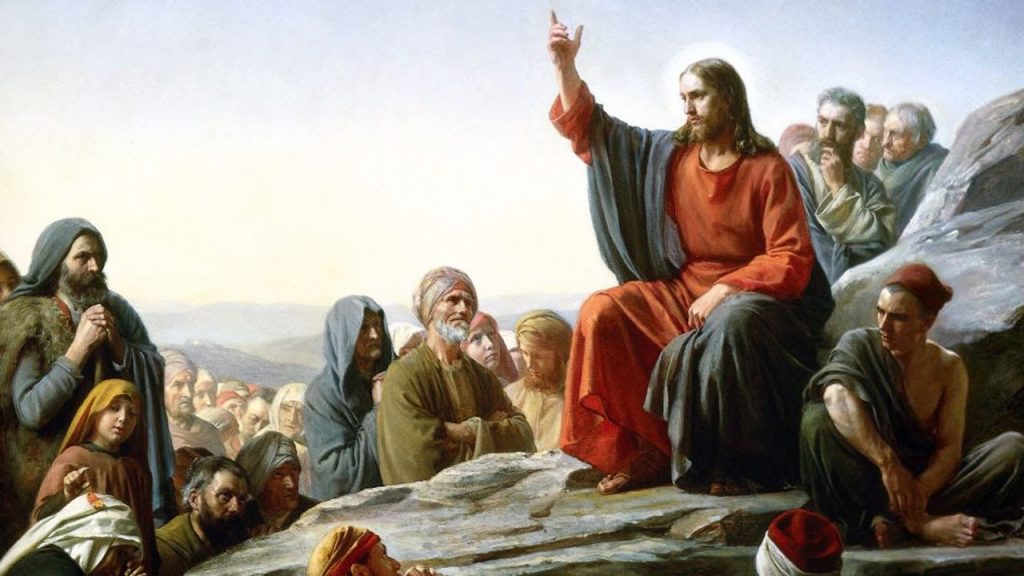

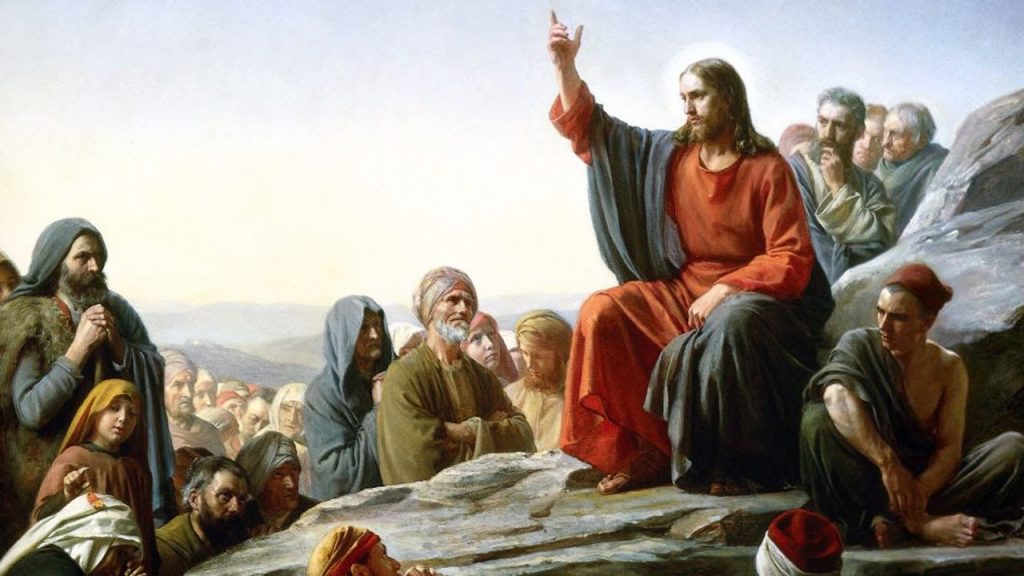

And He said to them, “O foolish men and slow of heart to believe in all that the prophets have spoken! Was it not necessary for the Christ to suffer these things and to enter into His glory?” Then beginning with Moses and with all the prophets, He explained to them the things concerning Himself in all the Scriptures (vv. 25-27).

In the earlier passage Jesus instructs the disciples ‘beginning with Moses and with all the prophets.’ In the later text he adds the Psalms to the Law of Moses and the Prophets. By adding the Psalms to this list, it is possible that Jesus is referring in an abbreviated way to the three major divisions of the Hebrew Bible: the law, the prophets, and the ‘writings,’ of which the Psalms were a major part. In other words, Jesus seems to be saying that the whole Old Testament had been written about him.

In these passages Luke, through words attributed to Jesus himself, is giving his readers a christological hermeneutic. This hermeneutic works in two ways. First, the life and ministry of Jesus is to be understood and interpreted in accordance with Old Testament categories; it is the framework by which we seek understanding of his life. This is important for it is not unusual for scholars to seek the understanding of Jesus in accordance with the milieu of the early church, or according to Greco-Roman categories, or even philosophical ideas and contexts from the modern era which may or may not have any real connection to first century Palestinian Judaism, and the biblical traditions that shaped and informed it.

Second, it has implications for how we read and understand the Old Testament itself. Luke (Jesus) suggests that the Old Testament serves as a witness to the divine activity that finds its telos and therefore its ultimate meaning in Jesus Christ. If this is the case, Old Testament interpretation cannot be content merely with a reading that seeks a historical reconstruction of the text, and its plausible meaning in its original context. Nor again with a reading which to a greater or lesser extent is unconcerned with the ancient historical and literary context, preferring a construction of meaning in accordance with the concerns and context of the modern reader.

The Old Testament is not merely a document in itself (and, of course, not merely “a document” but a collection of many and diverse documents), but a part of a movement toward a climax and a goal. This movement is not, of course, merely a literary movement, but a movement of faith grounded in the historical existence of a people of faith who regarded these particular writings as sacred, as “Scripture.” Jesus, too, regards them as Scripture, as prophetic, and as finding their telos and fulfilment in him.

Many other passages in Luke’s gospel indicates that Luke clearly read and understood the Old Testament in this way—and are suggestive that Jesus himself lay at the root of this practice: “Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Luke 4:21). And the same approach to the Old Testament is found in Matthew, John, and Paul.

On the road to Emmaus the two disciples failed to recognise Jesus; indeed, their eyes ‘were prevented’ from recognising him (v.16). Later, after Jesus revealed himself to them at the table, their eyes were ‘opened’ and they recognised him. And they recalled how their hearts ‘burned within them’ as Jesus explained the Scriptures to them. The eleven disciples, too, needed their minds to be ‘opened’ to understand the Scriptures (v. 45). Their hearts, their eyes, their minds: all needed to be opened to hear, to see, to understand the centre, the meaning, the truth of the Scriptures—Jesus Christ himself, crucified and risen.

We—modern readers and especially scholars—are sometimes critical of those who in previous eras “misread” the Scriptures, introducing “theology” into the text, and thereby doing injustice to its original authors, provenance, context, and audience, etc. (Though we are often prepared to do just that in the interest of modern idiosyncratic or ideological readings of the text!)

Luke, however, cites Jesus as reading in just this way. I suggest that following Jesus includes also following the manner in which he was devoted to Scripture, submitted to Scripture as an authority to which God’s people are subject, and also interpreted it as we see him do so here in Luke 24. We often applaud his interpretations: “I desire mercy and not sacrifice.” “The weightier matters of the law: justice, mercy, faithfulness.” “Can you not see that whatever goes into the mouth passes through the stomach and is discharged into the sewer?” But Jesus also says some things that we are not quite so sure about.

We might not read the text just as Jesus did—would that even be possible? But perhaps there is more here for us to learn, if we would be disciples of Jesus.

Lord,

Lord,