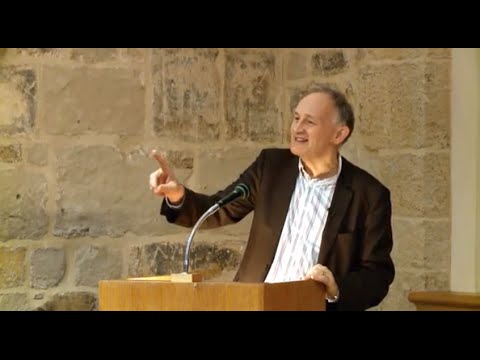

This week I have had opportunity to attend two events with Professor David Ford from Cambridge. The first was a seminar for faculty and HDR students from the various theological institutions around Perth. The theme of the seminar was a theological hermeneutic for reading the gospel of John. Professor Ford has been writing a theological commentary on John—for many years now—and brought a wealth of reflection on John’s gospel to the seminar. The second event was a public lecture at Murdoch University on “Healthily Plural Civilisation,” the third in a series of lectures on the theme Religion, Violence, and a Vision for Twenty-First Century Civilisation.

This week I have had opportunity to attend two events with Professor David Ford from Cambridge. The first was a seminar for faculty and HDR students from the various theological institutions around Perth. The theme of the seminar was a theological hermeneutic for reading the gospel of John. Professor Ford has been writing a theological commentary on John—for many years now—and brought a wealth of reflection on John’s gospel to the seminar. The second event was a public lecture at Murdoch University on “Healthily Plural Civilisation,” the third in a series of lectures on the theme Religion, Violence, and a Vision for Twenty-First Century Civilisation.

The public lecture began with a reading of the epigraph of celebrated Irish poet Micheal O’Siadhail’s forthcoming The Five Quintets. The poem, apparently, rehearses the history of modern western culture through engagements with luminaries in the fields of the arts, economics, politics, the sciences, and philosophy and theology, posing a vision for the humane continuation of the civilisation. It sounds like an extraordinary achievement.

Ford exposited the eight stanzas of the epigraph to distil a series of mottos or “headlines” toward a vision of peaceful and flourishing civilisation in the twenty-first century, with a particular appeal to the religions and the universities, the two locations of his life’s work. The eight mottos are

- Inspirational wisdom

- Imaginative creativity

- Generous economics

- Covenantal politics

- Wise sciences

- Deep reasonings

- Peaceful intensities

- Celebratory delight

I especially appreciated Ford’s implied exhortation to take daring risks for the sake of building peace-filled relationships and communities, and his insight that genuine formation occurs through intentional practices of face-to-face intensive conversations with colleagues and peers, and across generations.

Ford, I think, practises what he preaches. He regularly participates in inter-religious groups reading one another’s sacred texts and engaging in dialogue with them. Thus he reads Christian scriptures with Jews and Muslims, and presumably, Jewish and Islamic scriptures with the same groups. In a social context he tells of spending a week in a US prison with inmates gaoled for life, exploring Bonhoeffer’s Life Together. It seems he has drunk deeply in the wells of the Christian scriptures and tradition and has found a means of expressing that tradition in faithful and joy-filled life in and for the world.

I reproduce here the first and eighth of the stanzas from O’Siadhail’s epigraph:

Be with me Madam Jazz I urge you now

Riff in me so I can conjure how

You breathe in us more than we dare allow…

In all our imperfections we advance

Trusting in creation’s free-willed chance;

Sweet Madam Jazz in you we are the dance.