Read Psalm 13

Read Psalm 13

How long O Lord? Will you forget me forever?

How long will you hide your face from me?

How long shall I take counsel in my soul, having sorrow in my heart all the day?

How long will my enemy be exalted over me?

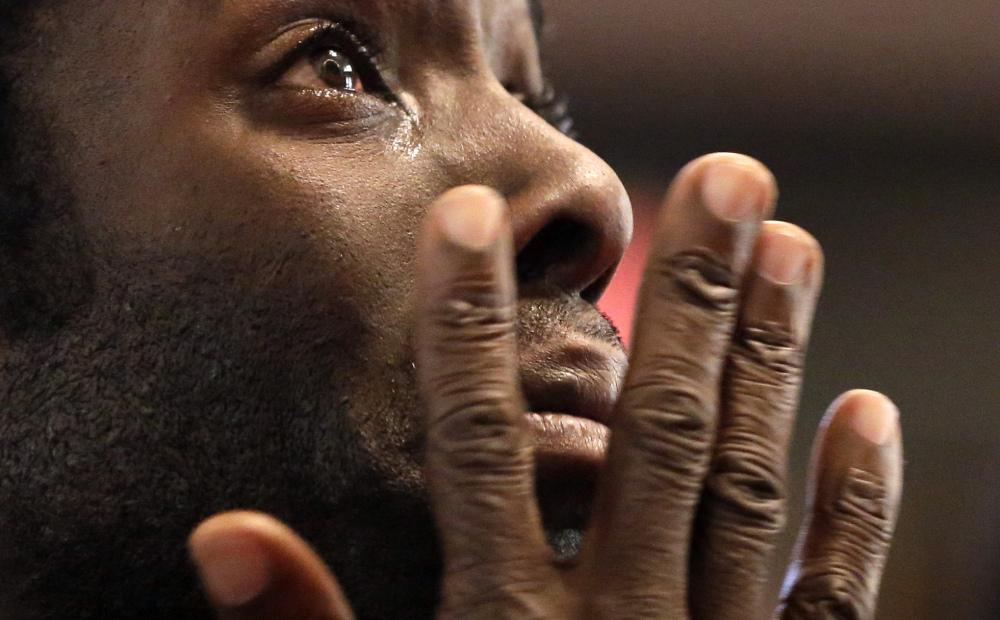

In these first two verses, the psalmist cries plaintively to the Lord who seems absent and unhearing, removed and uncaring. The words carry a sense of duration—interminable drudgery and aloneness, the fourfold repetition of ‘how long’ emphasising the silence and inactivity of God. The reader feels the tension; on the one side an unrelenting enemy and on the other an unresponsive God, the desperate psalmist caught helpless in the middle.

The enemy is singular, though the psalmist’s adversaries are multiple (cf. v.4). Craigie has no doubt that the enemy is “death” which is fast approaching, the singer being struck down with a life-sapping illness of some kind (Craigie, 142). Whether or not Craigie is correct, the circumstance is common in these early psalms of David: his enemies are ever present, and it seems they have the upper hand, their triumph assured. He has a sense of being alone and vulnerable in the world.

In the midst of this ‘dark night of the soul,’ the psalmist prays (vv. 3-4)—“lament is pointless unless it culminates in prayer” (Craigie, 142)—his faith evidently deeper than his experience, a bulwark against despair. Nevertheless, only the Lord can rescue him from the ever-present threat of death, and so he prays for God’s attention and action: “Consider and answer me, O Lord my God!” Kidner (77) notes that in the Old Testament “God’s ‘remembering’ and ‘seeing’ are not states of consciousness but preludes to action” (cf. Exodus 2:24-25). Thus the prayer is for deliverance, that God would turn again toward the psalmist, rather than ‘hide his face.’

Given the desperate tone of David’s lament, one is unprepared for the final couplet, where optimistic praise and trust seem incongruous with what has preceded. David has trusted in God’s lovingkindness, and so his heart shall rejoice in God’s deliverance. Because he has trusted, he will rejoice and he will sing. David’s faith is deeper than his experience because God is a deeper, more enduring, and more encompassing reality than his suffering. God’s love is steadfast despite his seeming absence; his salvation is assured; his grace is bountiful: therefore David will trust in anticipation of deliverance, and even rejoice and sing.

If the path is prayer, the sustaining energy is the faith expressed in verse 5. … However great the pressure, the choice is still his to make, not the enemy’s; and God’s covenant remains. So the psalmist entrusts himself to this pledged love, and turns his attention not to the quality of his faith but to its object and its outcome which he has every intention of enjoying (Kidner, 77-78).

The idea of being forgotten by God haunts us—could God, would God, actually forget us? Could God utterly overlook us or cast us behind his back? Does God hide his face from us, turn his back, keep his counsel, and ignore our hurt and dire straits? It is likely that no one who has tried to live a life of faith has not had the experience the psalmist describes here. It is an experience that Jesus, too, endured when on the cross he cried out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Our experience is often at odds with our expectation, and to the extent that a Christian’s expectation is that their faith should exempt them from the common trials of life, their expectation is unrealistic. Our expectations with respect to God, however, are another matter entirely. We expect God to care—and not only to care, but to act. Is this also unrealistic? Not according to this psalm.

Kidner captures something crucial with his observations about God’s covenant and David’s faith. David’s faith was not a vague or amorphous hope, but conviction born of a lifelong awareness of God’s covenant love toward his people, including himself. Because God is the ultimate reality of all things David cannot help but pray. His being caught in the tension between God and his enemy is an inevitability on account of his faith.

Even if it makes sense to be a practical atheist, as Ps. 10 suggests, distrust of divine oversight is not psychologically possible for those who cannot but believe in both the loving-kindness and punishing judgement of God as the moral grounding of society. To believe otherwise is to succumb to a morally chaotic reality in which might makes right and personal agency is denied, further robbing the sufferer of power (Ellen Charry, Psalms 1-50, 64).

David laments because he has faith, and prays for the same reason. Indeed the power and astonishing boldness of his prayer lies precisely here: God’s own integrity is at stake. In this psalm there is no confession of sin, no self-blame or condemnation, no blaming of the victim: the reason for divine silence is not judgement on the psalmist’s sin. “On the contrary, God’s failure to act reflects badly on God, for it enables the enemy to gloat” (v. 4; Charry, 63). And so David calls God to account with a boldness born of a faith so deeply embedded in his soul it contradicts the seeming finality of his experience.

Years ago the Corrs, an Irish singing group sang “forgiven, not forgotten.” The words, if not the song, catch the reality of covenant existence with God. We are forgiven. We are never forgotten. God’s covenant lovingkindness is the deepest reality of our lives, and of all reality, something upon which we can trust, and so also rejoice and sing. Lament turns to praise because God’s covenant love and grace is the defining reality of the psalmist’s existence.

I came across this prayer in Ray Anderson’s On Being Human. Then I prayed it as part of the congregation at Evensong in Adelaide last Sunday. It is the last line of the first stanza that grabs me: and there is no health in us. The prayer is from the Book of Common Prayer (1928), “Morning Prayer.”

I came across this prayer in Ray Anderson’s On Being Human. Then I prayed it as part of the congregation at Evensong in Adelaide last Sunday. It is the last line of the first stanza that grabs me: and there is no health in us. The prayer is from the Book of Common Prayer (1928), “Morning Prayer.”

Ezra 7:10

Ezra 7:10