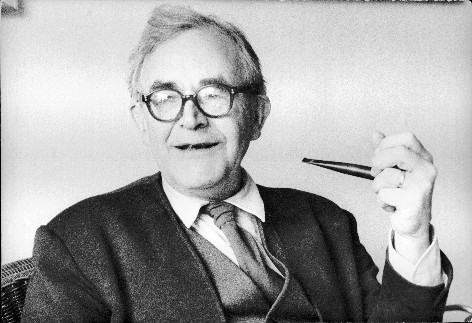

On September 21, 1953 Karl Barth gave an address at a meeting in Bielefeld of the Gesellschaft für Evangelische Theologie (Society for Evangelical Theology). It was published in a little collection of three essays entitled The Humanity of God. I am away from home at the moment and so cannot check Busch to find out what was going on at the time, but there is clear evidence in the lecture that Barth is engaging with some contemporary conversations and issues.

The most important thing to note at the outset is the subtitle of the lecture: “Foundation of Evangelical Ethics.” When Barth uses the term “Evangelical” he is referring to Protestant theology rather than evangelicalism as it is commonly known today. It may be, however, that Barth has in mind evangelical as gospel; what is beyond question, however, is that Barth is arguing for an ecclesial ethics, one specifically for the Christian community, rather than for humanity generally. Indeed, his ethics are possible only as an evangelical ethics and not otherwise.

The lecture progresses in four sections, the final section serving almost as an excursus. Although it seems natural to discuss the seeming reality of human freedom, Barth asks, “Why deny priority to God in the realm of knowing when it is uncontested in the realm of being? If God is the first reality, how can man be the first truth?”[1] Barth insists that beginning with God does not in any way imply the abrogation of human freedom, although some may want to argue the point with him. God’s freedom is not naked sovereignty or bare omnipotence, but relational freedom, the freedom in which God in covenantal grace gave and gives himself to humanity to be humanity’s God. God’s freedom is not freedom from, but freedom for. God is free to determine his own being to be God for us in and through Jesus Christ. God’s freedom was and is expressed in the gospel, and although surely God’s vision and purpose includes all his creatures, God’s particular interest concerns his human creature, indicated in his becoming human in his Son.

The well-known definitions of the essence of God and in particular of His freedom, containing such terms as “wholly other,” “transcendence,” or “non-worldly,” stand in need of thorough clarification if fatal misconceptions of human freedom as well are to be avoided. The above definitions might just as well fit a dead idol. Negative as they are, they most certainly miss the very center of the Christian concept of God, the radiant affirmation of free grace, whereby God bound and committed Himself to man, making Himself in His Son a man of Israel and the brother of all men, appropriating human nature into the unity of his own being.[2]

In the second section of the lecture, Barth turns his attention to human freedom and here his exposition runs entirely counter to modern expectations. Human freedom is indeed the gift of God, grounded in God’s own freedom. But God is not simply the source of human freedom; he is also its object and goal. The natural freedom given to humanity in creation has been lost through sin, by which humanity is alienated from God and self. Humanity does not now know its original freedom, nor indeed what it means to be human.[3] Barth therefore implies that we cannot know what freedom is and entails by phenomenological analysis of human existence and action. We can, of course, understand the human capacity of choice, decision, and action, but this in itself is not freedom.

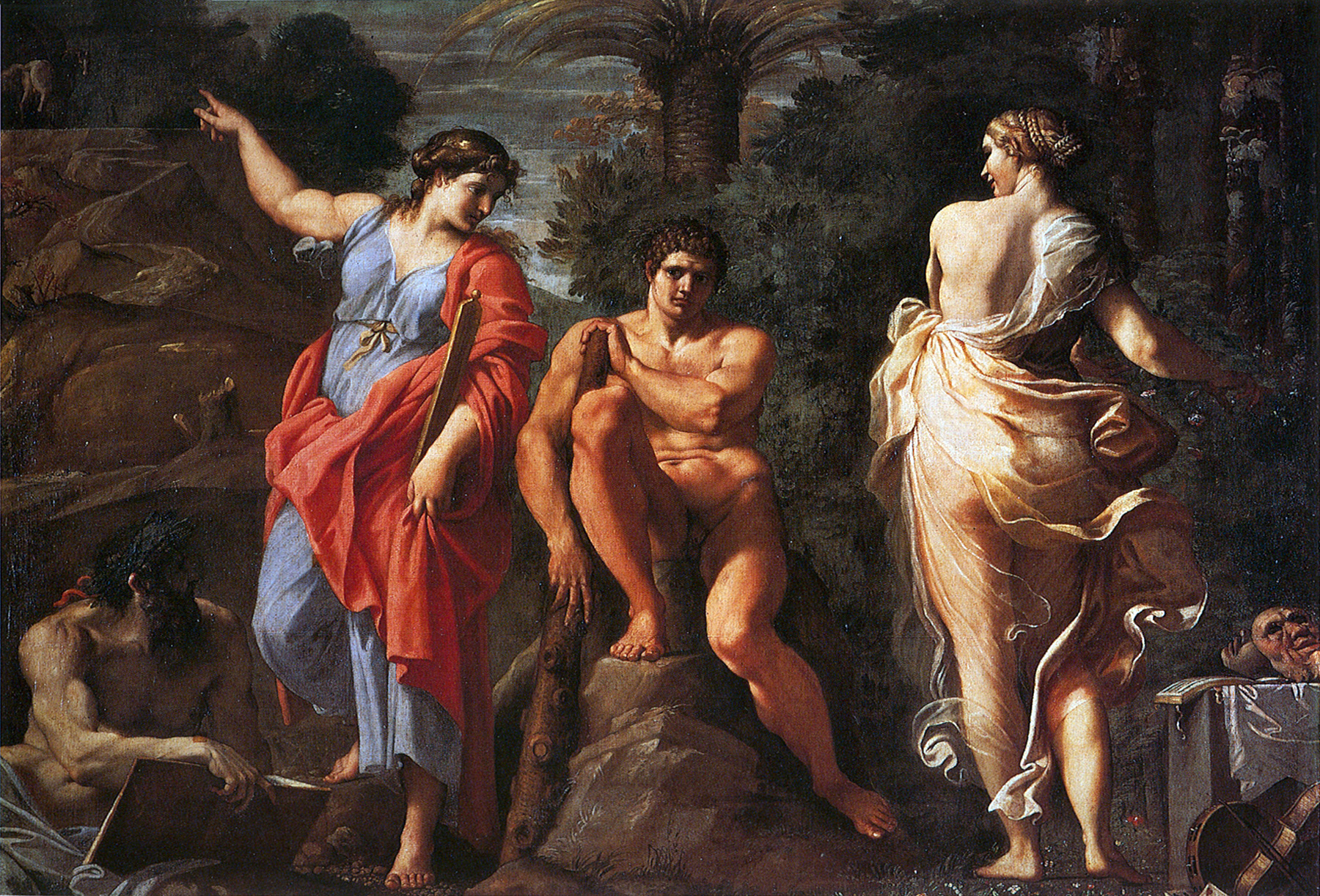

The concept of freedom as man’s rightful claim and due is equally contradictory and impossible. … Man has no real will power. Nor does he get it by himself. His power lies in receiving and in appropriating God’s gift. … God does not put man into the situation of Hercules at the crossroads. The opposite is true. God frees man from this false situation. He lifts him from appearance to reality. … It would be a strange freedom that would leave man neutral, able equally to choose, decide, and act rightly or wrongly! What kind of power would that be! Man becomes free and is free by choosing, deciding, and determining himself in accordance with the freedom of God. … Trying to escape from being in accord with God’s own freedom is not human freedom. Rather, it is a compulsion wrought by powers of darkness or by man’s own helplessness. Sin as an alternative is not anticipated or included in the freedom given to man by God.[4]

Apart from the gospel, then, humanity is “unfree.” What freedom is can be known only by understanding Christian freedom, that freedom which is given to humanity in Jesus Christ. Barth, echoing Luther, insists that freedom can be understood only in terms of “the freedom of the Christian.”[5]

To Be Continued …

[1] Karl Barth, The Humanity of God, trans., J. N. Thomas & T. Weiser (St. Louis: John Knox, 1960), 70.

[2] Ibid., 72.

[3] Ibid., 80.

[4] Ibid., 76-77.

[5] Ibid., 75, 82.

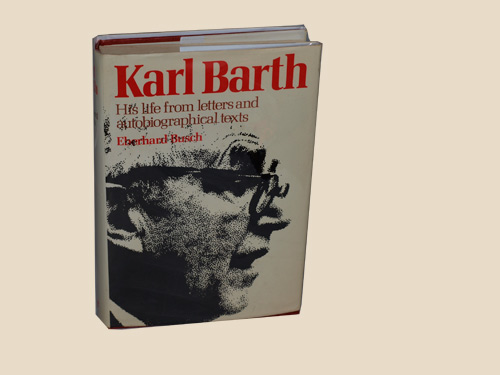

I already have all of these in real books, but it is a very good introductory special for those who want or like digital versions. There are selections from across the decades of Barth’s career, from the early 1920s through to a few final pieces from shortly before his death in 1968. Some of them are major works – The Münster Ethics (1928), Barth’s Gifford lectures The Knowledge of God and the Service of God (1937-1938), and Theology and Church, a collection of essays from 1920-1928. Others are occasional pieces, including lecture series, sermons, short theological pieces, and Barth’s tribute to Mozart, with whom he carried on a life-long love affair. Also included in the set is the massive biography by his friend and student Eberhard Busch, which I have reviewed in three posts under the title of

I already have all of these in real books, but it is a very good introductory special for those who want or like digital versions. There are selections from across the decades of Barth’s career, from the early 1920s through to a few final pieces from shortly before his death in 1968. Some of them are major works – The Münster Ethics (1928), Barth’s Gifford lectures The Knowledge of God and the Service of God (1937-1938), and Theology and Church, a collection of essays from 1920-1928. Others are occasional pieces, including lecture series, sermons, short theological pieces, and Barth’s tribute to Mozart, with whom he carried on a life-long love affair. Also included in the set is the massive biography by his friend and student Eberhard Busch, which I have reviewed in three posts under the title of