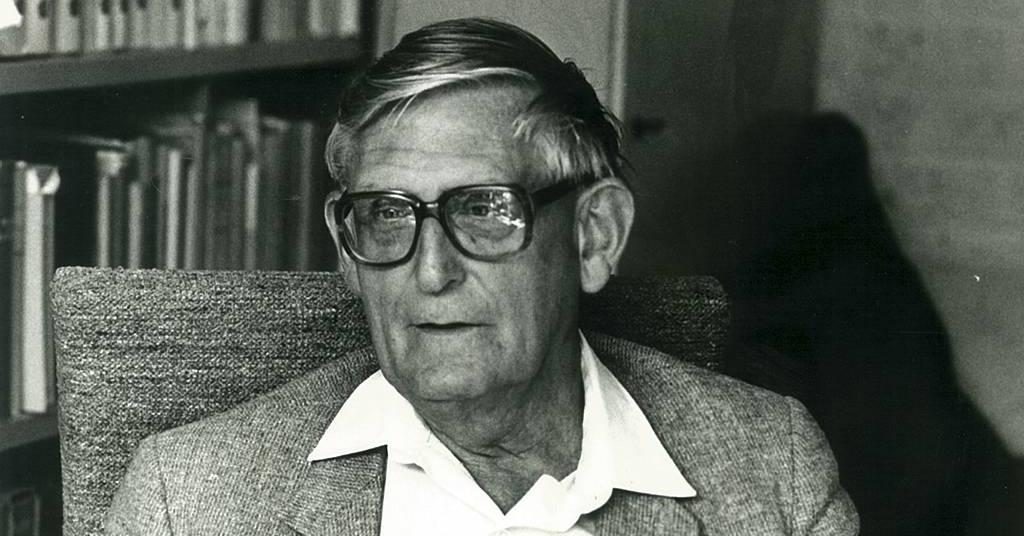

In his classic work Jesus – God and Man (German original 1964) Wolfhart Pannenberg argues for the sinlessness of Jesus, as most of the Christian tradition has done.

In his classic work Jesus – God and Man (German original 1964) Wolfhart Pannenberg argues for the sinlessness of Jesus, as most of the Christian tradition has done.

Pannenberg begins his treatment of the topic with a survey of the doctrine in the history of theology, beginning with the New Testament texts which affirm Jesus’ sinlessness. These, Pannenberg argues, together with the earliest Patristic theologians, assert that Jesus did not sin, although his humanity was like ours in every respect. Later Christian theology shifted this understanding of Jesus’ sinlessness, however, to an affirmation of his impeccability: the idea that Jesus could not sin, and so that his humanity was decisively different to ours. Augustine explained this with recourse to the ideas of original sin and virgin birth, and the conciliar tradition with recourse to the impersonal humanity of Jesus in the anhypostasia-enhypostasia doctrine.

In the nineteenth, however, the idea of human personality and agency, along with questions about the doctrine of orginal sin, led some theologians to locate Jesus’ sinlessness in his “inner life,” or his “moral exemplarism.”

Pannenberg rejects all these options, and develops his argument in three moves. First, he follows the witness of the New Testament and the earliest theologians, that Jesus’ sinlessness is to be understood as his “not committing any sin” during his earthly life, rather than any concept of his incapacity to sin. He rejects these later views because they render the biblical testimony to his temptations and struggles impossible to understand, and so his humanity as qualitatively distinct from normal human life.

Second, while he rejects the Augustinian doctrine of original sin as an explanation for the transmission of sin to each succeeding generation, he finds in it a valid description of the empirical existence of humanity, if not a description of human essence.

If sin is not associated with the essence of the divine destiny of man, but with the structure of present human existence, one cannot conceive of a natural sinlessness of Jesus. It is inconceivable that Jesus was truly man, but that in his corporeality and behavior he was not stamped by the universal structure of centeredness of animal life that is the basis of the self-centeredness of human experience and behavior, but which becomes sin only in man. The conception that at the incarnation God did not assume human nature in its corrupt sinful state but only joined himself with a humanity absolutely purified from all sin contradicts not only the anthropological radicality of sin, but also the testimony of the New Testament and of early Christian theology that the Son of God assumed sinful flesh and in sinful flesh itself overcame sin (362).

Thus Pannenberg argues that the eternal Son did indeed take sinful flesh (Romans 8:3) when he became human, and hence faced the kind of temptation and struggle that all humans face. And it was from within this solidarity with humanity generally, and not exempted from it, that he overcame sin. That he did so is known – both to himself and to us – only in the resurrection.

This is Pannenberg’s third move. It is pointless for us to try to prove the sinlessness of Jesus on the basis of his virgin birth, or his “inner life,” or his moral superiority. The testimony of his life, like that of every person, is ambiguous. Only in the light of the resurrection can we assert Jesus’ sinlessness, and apply it retrospectively to his life on the basis of the divine vindication expressed in this event.