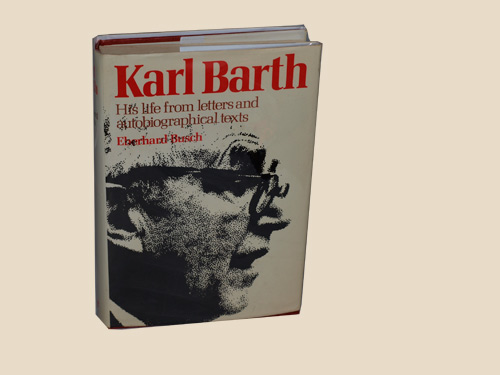

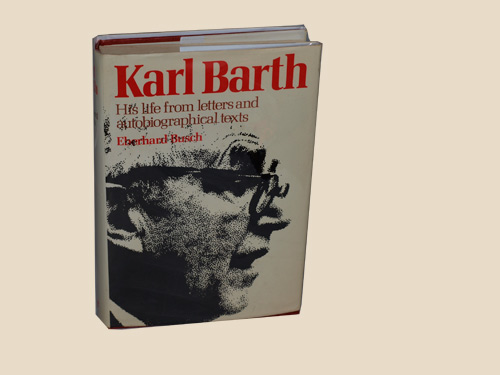

Although first published in German in 1975, and in English translation in 1976, Eberhard Busch’s Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts is still the go-to text for the story of Karl Barth’s remarkable life and theological development. That is not to say that this is the final word on his life; far from it, for we are still awaiting a full-scale critical biography. Perhaps someone might undertake this task for the fiftieth-anniversary of Barth’s death in 2018. (Do any German-speaking historians read this blog?) This work is not so much a biography as an account of Barth’s life, almost an itinerary, or a leafing through his diary, with Barth himself providing a running commentary on the various episodes of his life, the people he met, and the momentous events and days in which he participated.

Although first published in German in 1975, and in English translation in 1976, Eberhard Busch’s Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts is still the go-to text for the story of Karl Barth’s remarkable life and theological development. That is not to say that this is the final word on his life; far from it, for we are still awaiting a full-scale critical biography. Perhaps someone might undertake this task for the fiftieth-anniversary of Barth’s death in 2018. (Do any German-speaking historians read this blog?) This work is not so much a biography as an account of Barth’s life, almost an itinerary, or a leafing through his diary, with Barth himself providing a running commentary on the various episodes of his life, the people he met, and the momentous events and days in which he participated.

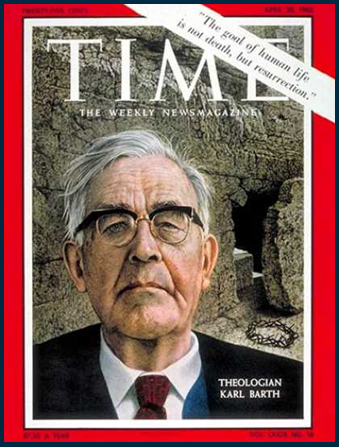

Over the course of his life Barth wrote the 6,000,000 or so words of his unfinished magnum opus Church Dogmatics, hundreds of formal lectures and articles, hundreds more lectures to his students, hundreds of sermons (especially while pastor at Safenwil), and thousands of letters. Busch has carefully mined all these resources and more besides, such as radio broadcasts and recordings of class conversations, in order to let Barth tell, in his own words, the story of his life. The result is a large book of over 500 pages covering the whole of his life from his early childhood in Basel as a lively and perhaps even somewhat wild boy, through his student and pastoral years, to his early career in Göttingen and Münster as young professor, his participation in the church struggle against Hitler and the Nazi ideology which engulfed the nation and church, through the years of his global prominence, and to the final twilight years in which he still remained active and involved in theology despite advancing age and associated health concerns.

Barth’s theological development and commitments are naturally a primary focus of the work, and Busch has included sufficient summaries, excerpts and commentary to give the reader a good sense of Barth’s thought at each particular phase of his career. But the book also has extensive accounts of his family and friendships, his interactions, journeys and conflicts, which allow the very human and at times flawed character of the man to be clearly seen. The inclusion of more than 100 photographs add depth, colour and interest to the story, and the several maps, family tree, and extensive references help the reader, especially those not familiar with the history or geography of Barth’s time, to read profitably.

Eberhard Busch has done us a salutary service in preparing this account. I recommend it highly to any and all theological students, and anyone participating in Christian ministry. It is a story of a man living in extraordinary times, whose uncommon intellect, abundance of hard work, and network of relationships issued in a remarkable life of witness to Jesus Christ, and a substantial contribution to the work of church in his day.

I have just read, for the first time actually, the whole book from cover to cover. Previously I have only read those earlier sections immediately relevant to my work. Reading the whole has given me a fresh appreciation and sense of this remarkable life. Over the next few days I will record some observations of those things which stood out to me as particularly significant.

I have just read, for the first time actually, the whole book from cover to cover. Previously I have only read those earlier sections immediately relevant to my work. Reading the whole has given me a fresh appreciation and sense of this remarkable life. Over the next few days I will record some observations of those things which stood out to me as particularly significant.

Extraordinary Times

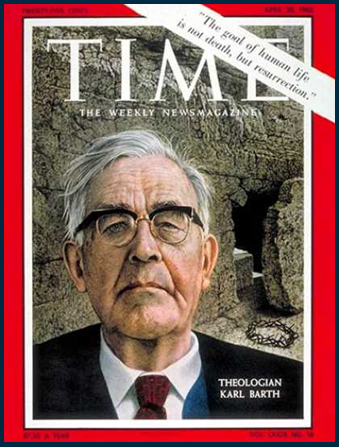

Born May 10, 1886 and died December 10, 1968, Barth lived through two world wars and was deeply involved in both—not so much as a soldier, although he did enlist in Switzerland’s defence force in WWII, despite being in his 50s—but in thinking through what it meant to be church, to be a Christian, to do theology, in such turbulent and distressing times. Other movements included the rise of Christian socialism in Switzerland, the communist revolution in Russia and then the rise of international communism, especially the Stalinist variety, the attempted putsch in Germany, the Weimar Republic and its failure, the Confessing Church, Barmen, the atomic bomb, the eastern bloc and the Cold War: maybe it is the case that extraordinary times call for extraordinary characters. Barth was certainly an extraordinary man in extraordinary times.

Character

One of the primary characteristics to emerge from his story was Barth’s energy: he was a vibrant and dynamic person, accomplishing a vast amount of work and maintaining a punishing schedule of classes, meetings, lectures and international trips. He certainly slowed as he aged, but even then maintained quite high levels of participation in affairs theological, ecclesial and civil. He was a diligent networker and correspondent, obviously an extrovert, who enjoyed people and maintained enduring friendships and other associations over the course of his life. Yet there was also a certain pugnacious aspect to his character, evident in childhood scraps with his peers, his take-no-prisoners approach to the dispute with Brunner, his brother’s complaint that Karl was ‘a man who would brook no opposition’ (269). Thus he managed to lose friends and alienate colleagues as well, at times, being sharply critical of those with whom he disagreed. Especially during the church struggle of the 30s, the severity of the circumstances seemed to demand an “all-or-nothing,” black and white approach to the issues; one either sided with or against the gospel, and no sitting on the fence was possible.

And then, of course, his uncommon intellect, nurtured by the formidable German education system. Barth (and his associates) were deeply immersed in biblical studies and theology, had mastery of literature and philosophy, Greek, Hebrew, Latin (Barth was also fluent in French and then also learned English), the Patristic fathers and the Reformers, as well as living in the golden age of German culture prior to WWI. This, of course, also suggests his privilege, for only those of the right class got to go to university, and to participate in the kinds of circles in which Barth naturally fit all his life. He came from Old Basel society, from generations of pietist ministers on both sides of his lineage. Early in his life he rejected pietism as a way of being Christian, and yet it is evident that the influence of his pietist heritage marked him all his days: religion and theology could never simply be intellectual, but always was oriented to the good and gracious God, with “a touch of enthusiasm.”

I already have all of these in real books, but it is a very good introductory special for those who want or like digital versions. There are selections from across the decades of Barth’s career, from the early 1920s through to a few final pieces from shortly before his death in 1968. Some of them are major works – The Münster Ethics (1928), Barth’s Gifford lectures The Knowledge of God and the Service of God (1937-1938), and Theology and Church, a collection of essays from 1920-1928. Others are occasional pieces, including lecture series, sermons, short theological pieces, and Barth’s tribute to Mozart, with whom he carried on a life-long love affair. Also included in the set is the massive biography by his friend and student Eberhard Busch, which I have reviewed in three posts under the title of

I already have all of these in real books, but it is a very good introductory special for those who want or like digital versions. There are selections from across the decades of Barth’s career, from the early 1920s through to a few final pieces from shortly before his death in 1968. Some of them are major works – The Münster Ethics (1928), Barth’s Gifford lectures The Knowledge of God and the Service of God (1937-1938), and Theology and Church, a collection of essays from 1920-1928. Others are occasional pieces, including lecture series, sermons, short theological pieces, and Barth’s tribute to Mozart, with whom he carried on a life-long love affair. Also included in the set is the massive biography by his friend and student Eberhard Busch, which I have reviewed in three posts under the title of