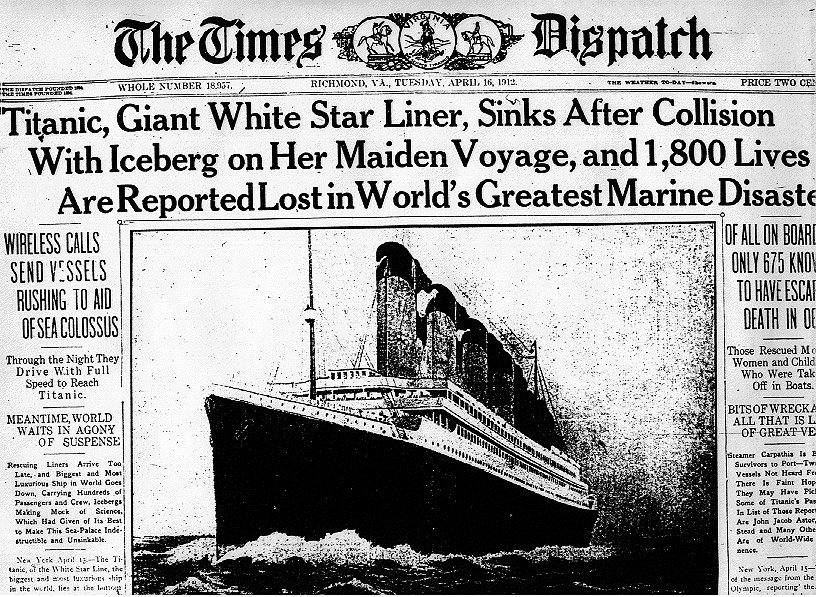

This week we celebrate ANZAC day, remembering the Australian servicemen and service-women who have fought and served in other conflicts. Two years ago it was the centenary of the Gallipoli landing, and the year before that, the 70th anniversary of D-Day, the decisive victory against a devastating and ruthless enemy. What might have happened if that victory had not occurred? One Australian survivor of D-Day was Bob Cowper from Adelaide. Cowper had been a Mosquito pilot, helping keep the skies clear above the massive landing fleet. “It was the greatest military operation in the world’s history,” he said. “To think that we fought the battle that made the world a safer place was very satisfying” (“Our Australian Witnesses to the D-Day Horror” Weekend Australian, May 31, 2014, 20). Many others, of course, were not so fortunate and the article tells some of the stories of those who did not return from the battle.

This week we celebrate ANZAC day, remembering the Australian servicemen and service-women who have fought and served in other conflicts. Two years ago it was the centenary of the Gallipoli landing, and the year before that, the 70th anniversary of D-Day, the decisive victory against a devastating and ruthless enemy. What might have happened if that victory had not occurred? One Australian survivor of D-Day was Bob Cowper from Adelaide. Cowper had been a Mosquito pilot, helping keep the skies clear above the massive landing fleet. “It was the greatest military operation in the world’s history,” he said. “To think that we fought the battle that made the world a safer place was very satisfying” (“Our Australian Witnesses to the D-Day Horror” Weekend Australian, May 31, 2014, 20). Many others, of course, were not so fortunate and the article tells some of the stories of those who did not return from the battle.

In some indefinable way, our soldiers who have gone before us represent us, whether for good or for evil. We remember this representation at ANZAC day. In some very real way, we are tied up with them, all in it together. And it remains a very real question: if they did not do what they did, could we, would we be who we are?

For Israel, too, battles were a fact and necessity of life. Psalm 20 has its genesis in the reality of battles and enemies. This brief psalm is a wonderfully positive benediction which masks, perhaps, the dire circumstances presupposed. An enemy, equipped with chariots and horses—the best military equipment of the day—has drawn near. The king and his soldiers are prepared for battle. Sacrifices have been offered, and now the people add their benediction (vv.1-5). The king responds with assurance in verse 6. Then the people declare their trust in God in vv. 7-8, and conclude with an urgent cry for victory in verse 9.

Reading the Psalm (vv. 1-5)

The Lord answer you in the day of trouble!

The name of the God of Jacob protect you!

May he send you help from the sanctuary, and give you support from Zion.

May he remember all your offerings, and regard with favour your burnt sacrifices. Selah

May he grant you your heart’s desire, and fulfil all your plans.

May we shout for joy over your victory,

and in the name of our God set up our banners.

May the Lord fulfil all your petitions.

Eleven times the word You or Your appears in the singular: these first five verses constitute a wonderful benediction of the people toward the king. They are pronouncing a blessing of divine victory upon the king before he goes to battle. And why? Because his victory is their victory; his defeat, theirs. He represents the whole nation and their destiny is intertwined: they are all in this together. Their nine blessings (or is it eleven?) all point to a comprehensive victory against their enemy.

Note these nine blessings, and also see the chiastic pattern formed by them.

1a / 5c … The Lord answer you / fulfil all your petitions

1b / 5ab … The Name of the Lord protect you / The Name of the Lord

2 / 4 … May he send you help and support you / May he grant you your heart’s desire and fulfil all your plans

3 … May he remember all your offerings and regard with favour your burnt sacrifices.

The central strophe of the pattern highlights that which is central: that at the heart of this blessing is a recognition of covenant faithfulness toward God represented by a life of worship and devotion. “May he remember all your offerings.”

David comes to the present crisis with a long history of love and devotion to God. What we do day by day in times of peace prepares us for times of war. When our devotional life is a habit we are well served for battle (Williams, Psalms 1-72 Communicator’s Commentary, 160).

What does it mean to be “battle-ready?” Are you dressed for battle in the armour of God? Do you have a history of devotion with God, a history of faith and prayer, worship and love? Worship and warfare seem like the most unlikely companions, but in God’s kingdom, in spiritual warfare, they go together.

The commentators suggest that the verbs in this passage are in an unusual tense they call the prophetic perfect. That is, the words pronounce a blessing which is still in the future, still yet to happen, but so sure and certain, they speak of it as though it is already accomplished. Then in verse 9 they will cry out to God in an explicit prayer for victory, “Save, O Lord! Give victory!” But this does not contradict the faith-filled benediction of these opening verses. Faith works both ways.

Mark 11:22-25

Jesus answered them, ‘Have faith in God. Truly I tell you, if you say to this mountain, “Be taken up and thrown into the sea”, and if you do not doubt in your heart, but believe that what you say will come to pass, it will be done for you. So I tell you, whatever you ask for in prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be yours.

‘Whenever you stand praying, forgive, if you have anything against anyone; so that your Father in heaven may also forgive you your trespasses.’

In this text Jesus teaches two complementary operations of faith: faith by saying it, and faith by praying it. The first is an exercise of spiritual authority, a faith-filled or prophetic pronouncement. The second is simply a classic form of prayer. Sometimes faith is exercised by an authoritative declaration or command, sometimes by petition to God.

In this psalm the congregation exercise faith in both ways. I wonder how much boldness it would have taken to declare victory in the face of such a fearsome enemy, equipped with horses and chariots? This is all the more so when we remember that Israel’s king was forbidden to multiply horses and chariots (Deut 17:16). But they do declare this blessing and in so doing, look forward to God’s blessing, God’s help and salvation.

Psalm 20:6-9

Now I know that the Lord will help his anointed;

he will answer him from his holy heaven

with mighty victories by his right hand.

Some boast in chariots, and some in horses,

but we will boast in the name of the Lord our God.

They will collapse and fall,

but we shall rise and stand upright.

Give victory O Lord;

May the King answer us in the day we call. (NASB)

Note: many versions translate verse 9: “O Lord, save the king!

May he answer us when we call” (see, e.g., ESV; NIV; NRSV)

Verse six is the king’s response to this blessing, his agreement with this blessing. Verses seven and eight return to the corporate voice, affirming their trust in God. Notice, again, the third mention of the Name of the Lord. To boast in the name of the Lord is to make mention of his name, to remember, invoke or proclaim his name.

The Name of the Lord represents his own person and presence, character and authority. To have faith in his name is to recognise our relationship with God—at his initiative—including his claim on us. Jesus authorises us to pray in his name (John 16:23-24). Proverbs 18:10 says that “the name of the Lord is a strong tower; the righteous runs into it and is safe.” David went out against Goliath in the name of the Lord (1 Samuel 17:45).

Is it true that God will give us whatever our heart desires, whatever we ask for “in his name”? To ask in his name is to ask in accordance with his person and character. The promise that God would grant David’s heart’s desire was made to someone whose heart was aligned with God’s in sacrifice, devotion and worship. He had a heart after God’s own.

The psalm ends with an explicit petition for victory in verse nine. Notice the interplay between the king and the King: behind the earthly ruler stands the heavenly ruler of Israel. Notice, too, that the day of trouble (v. 1) is the day we call (v. 9).

Many commentators believe this psalm represented a liturgy that was practiced regularly in the temple worship. In this liturgy, the reality of the joint destiny of the people of God was enacted.

Battle Ready

Our situation, of course, is vastly different to that of ancient Israel, and it is not likely that we will face the same kind of battle conditions they did. Nonetheless, the psalm still speaks to the reality of our lives: life is a battle. For some people it is more of a battle than for others. All of us, though, are likely to be drawn into various kinds of battles where our life or our sanity, our work or our witness, our future or our family is threatened by powers and circumstances external to us, perhaps stronger than us. Christian life and ministry is a battle, a never-ending engagement with principalities and powers and rulers of the darkness of this world (Ephesians 6:10-12). Maintaining a faithful marriage or sexual purity may prove a great battle for some. Raising our children, paying our bills, maintaining a gentle spirit in the face of provocation—these and much more can be a great battle. What are you battling? You’ve heard of Howard’s battlers; Christians can be battlers too. How, then, does this psalm help us become “battle ready”?

- This psalm will remind us that we are in a spiritual battle and thus need to grow in our understanding of the various weapons of our warfare (2 Corinthians 10:3-5), the ways of faith and spiritual authority (1 Peter 5:8-9). We should develop our faith in the name of Jesus until it truly becomes for us “a high tower” of safety and refuge in times of trouble.

- Worship and warfare belong together. We have already mentioned the necessity and centrality of worship and devotion. If we want the Lord to answer us in the day of trouble, we must call upon his name. It is much easier to do so when we are already on speaking terms, in good relationship.

- We are all in this together, and we will stand or fall together. This is especially true of families and of churches. The people depended on the king and the armies; the king and the army depended on the people. We need each other because we are inter-dependent. We need each other’s faithfulness, steadfastness, devotion, faith, prayer and blessing. That this psalm was preserved, that it became part of the temple worship collection suggests that the corporate gathering, prayer and faith of the people was absolutely crucial.

- Behind the king is the King. God is with us – “at the heart of Hebrew theology lay the conviction that God was involved in their historical experience” (Craigie, Psalms 1-50 WBC, 188). Jesus is our king, and he has gone into battle on our behalf, and has won the decisive victory. We still face fierce battles, mopping-up battles, but he is with us; and as we go forth in his name, victory is assured – Hallelujah!

I am preaching again at Harmony Baptist Church today. Last week my message from Psalm 77 was centred around the devotional practice of meditating on the Scriptures. Today’s message is also focussed on the reception and use of the Bible in the Christian life, this time in terms of study rather than meditation.

I am preaching again at Harmony Baptist Church today. Last week my message from Psalm 77 was centred around the devotional practice of meditating on the Scriptures. Today’s message is also focussed on the reception and use of the Bible in the Christian life, this time in terms of study rather than meditation.

Human Origins: How did we come to be here?

Human Origins: How did we come to be here? good’ be understood in terms of some kind of metaphysical perfection, or might it be understood in terms of the value God the Creator places upon his work? English theologian Colin Gunton suggested that, “Rather like a work of art, creation is a project, something God wills for its own sake and not because he has need of it” (Colin E. Gunton, “The Doctrine of Creation,” in The Cambridge Companion to Christian Doctrine, 142). Such an interpretation suggests that God’s work of creation was not the end of his purpose, but the beginning of a project playing out across history and moving toward a divine purpose and climax. In this view, the immanent God accompanies his creation, at times doing new things, providentially guiding the creation toward his appointed goals.

good’ be understood in terms of some kind of metaphysical perfection, or might it be understood in terms of the value God the Creator places upon his work? English theologian Colin Gunton suggested that, “Rather like a work of art, creation is a project, something God wills for its own sake and not because he has need of it” (Colin E. Gunton, “The Doctrine of Creation,” in The Cambridge Companion to Christian Doctrine, 142). Such an interpretation suggests that God’s work of creation was not the end of his purpose, but the beginning of a project playing out across history and moving toward a divine purpose and climax. In this view, the immanent God accompanies his creation, at times doing new things, providentially guiding the creation toward his appointed goals.