The 2015 ANZATS conference got off to a good start today. This year we are meeting in Sydney at the offices of the Sydney College of Divinity. There are 70-80 delegates, with Scott Stephens (Online editor of religion and ethics for the ABC) addressing the plenary sessions.

The 2015 ANZATS conference got off to a good start today. This year we are meeting in Sydney at the offices of the Sydney College of Divinity. There are 70-80 delegates, with Scott Stephens (Online editor of religion and ethics for the ABC) addressing the plenary sessions.

Scott’s topic today was “The Kingdom of the Popular Soul: How Truth became Opinion, and Opinion became Fashionable.”

His lecture was basically an overview of some key developments in the history of popular media and mass communications, and how these developments have helped shape discourse in the arena of ‘public opinion.’ His discussion of Kierkegaard’s ferocious opposition to the popular press was a highlight of the day. My brief note here probably does not do justice to what I heard…

For Kierkegaard, opinion is irresponsible speech, something we have to wear into the public realm, opinion as a ‘fashion statement.’ Irresponsible speech is to ‘chatter.’ It is the annulment of the essential distinction between silence and speech. Speech derives from thoughtful reflection. Silence as a means of reflection, is therefore a moral activity; to speak is then to become responsible, to commit oneself. The opinion makers have therefore cheapened public discourse, forcing opinions, chattering… The pressure to have an opinion, to have to ‘say something,’ leads to irresponsibility.

Other sessions I attended today were:

1. Anne Elvey – “Compassion as Method in (Public) Theology.”

To have compassion is to act in concrete ways toward others in ways which seek to alleviate their suffering, to include them in community, etc. What impact would a commitment to live and act compassionately towards others, including the non-human creation, have on our theological work?

2. Geoff Thompson – “A God Worth Talking About for a Life Worth Living: The Accidental ‘Public Theology’ of Terry Eagleton.”

This was a very interesting lecture on the way a non-theologian is introducing ideas from classic theology into public discourse in order to ‘repair culture.’ Eagleton is a talented polemicist, yet he gains a hearing for Christian ideas, introducing and explaining them as ideas which are relevant to the way we think and live. Thompson suggests that Eagleton seems to have convictions about just how big the Christian story is; convictions many Christians and even theologians seem to have forgotten. I came away from this lecture wondering whether we should be trying to do “public theology,” or to do ordinary theology in publicly accessible ways. I suggest the latter is the case.

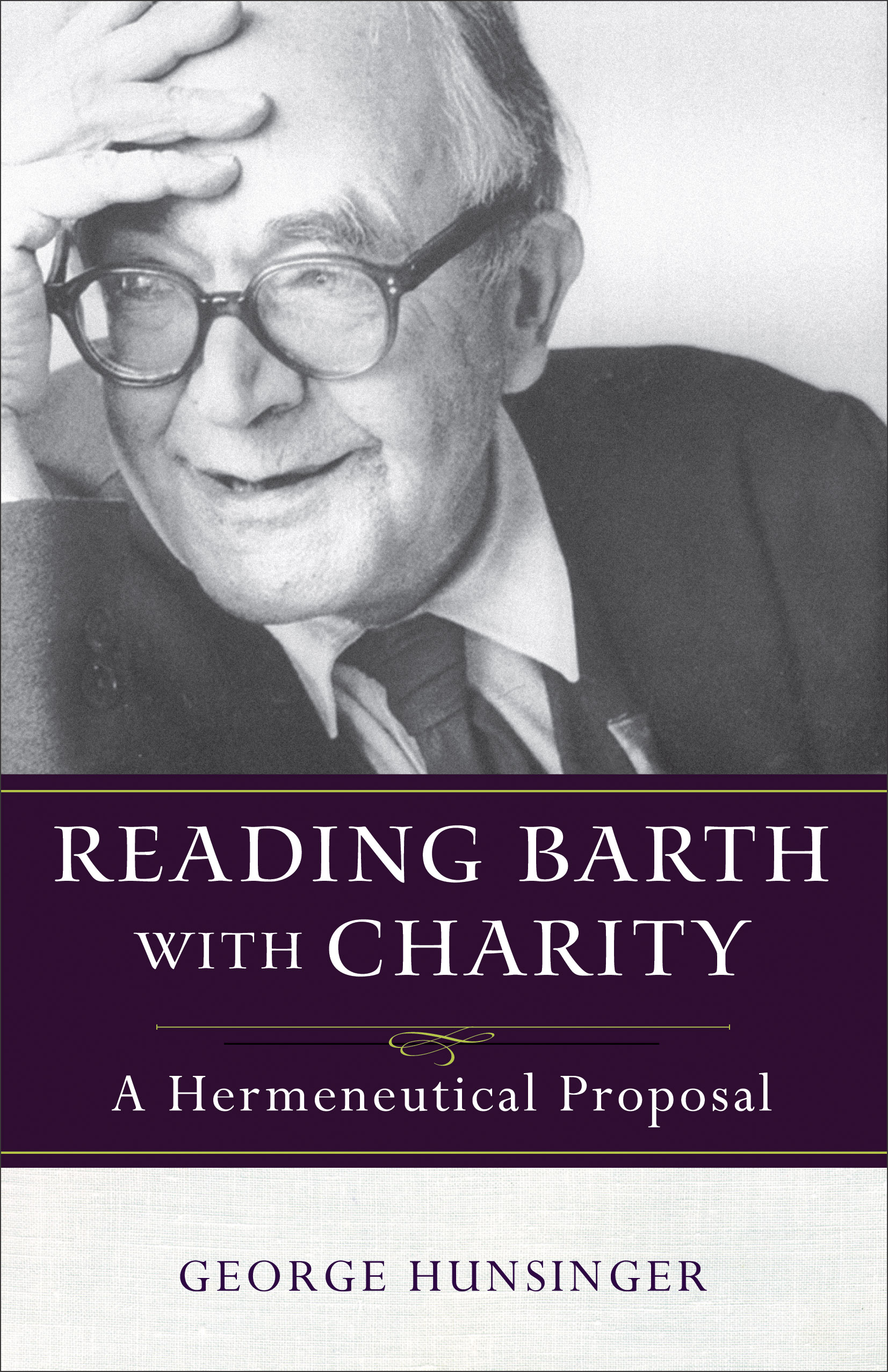

3. Scott Kirkland – “Toward an Aesthetics of the Cross: Barth, Divine Beauty, and the Persuasiveness of Divine Speech.”

The first lecture of the Barth Study Group explored Barth’s doctrine of the divine glory, the beauty of God seen in the work of Jesus Christ, and especially at the cross. What would otherwise be understood as ugly and violent becomes a thing of beauty, not from some kind of objective and disinterested stance (i.e. a kantian view of beauty), but from a perspective of faith, in which the true beauty of the self-giving God is revealed to us.

And I presented my first paper: “An Ethics of Presence and Virtue in Psalms 9-11” arguing for a fully ‘religious’ ethic. Two really interesting questions were asked at the end:

(a) Is it wrong to advocate both a virtue ethic and an ethic of imitation? Are not these two forms of ethics at odds with one another? I suggested, within the context of Psalms 9-11, that no, they are not. This is an ethical life grounded in the community of God’s people living into the narrative of God’s redeeming work as witness in Scripture, including the kind of God that God is, and the kind of people God calls us to be.

(b) If the psalms so commend such an ethic, how might they be more fruitfully used in congregational worship to stimulate such ethical response, especially in the free church tradition where they are not used liturgically? Great question! I think we need to work on that one…