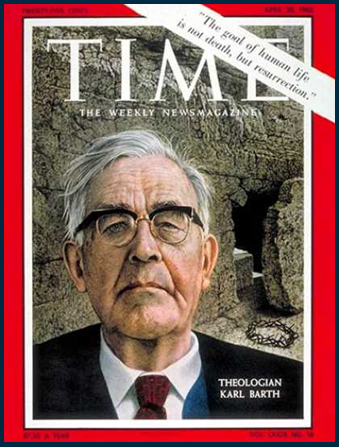

Today I continue to post some observations drawn from Eberhard Busch’s Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts which I highly recommend.

Today I continue to post some observations drawn from Eberhard Busch’s Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts which I highly recommend.

God

The living and true God, the high and holy God, the transcendent and immanent God, the one God revealed as Father, Son and Holy Spirit in the person of Jesus Christ, God the Creator, Reconciler and Redeemer, God the Wholly Other, the Good and Gracious God who has come to us and judges and calls us in Jesus Christ: this God was the centre of Barth’s existence, from whom and towards whom he lived. It was the reality of this God who ever stands over against us which drove Barth’s break with the Liberal theology of his student years, and it was the knowledge of this God revealed decisively in Jesus Christ that continued to drive his innovative theology over the course of his career.

Scripture

Dismayed by the capitulation of all but one of his Liberal teachers to the war policies of Kaiser Wilhelm in 1914, Barth and his friend Eduard Thurneysen knew they could no longer follow this theology, and so sought a “wholly other” foundation for theology (it was Thurneysen who first used the famous phrase). They tried starting again with Kant, Schleiermacher and Hegel, but found them more and more dissatisfying. In the end, they turned again to Scripture and found, “Lo, it began to speak to us.” Barth began his career with exegesis, especially of Romans, and it was this work which catapulted him into public awareness. For much of his career he taught not only theology but also New Testament exegesis. His Church Dogmatics abound with extended passages of biblical exegesis and exposition. About to be expelled from Germany by the Gestapo in 1935, he said in his final words to this students:

We have been studying cheerfully and seriously. As far as I was concerned it could have continued in that way, and I had already resigned myself to having my grave here by the Rhine! I had plans for the future with other colleagues who are either no longer here or have been away for a long time – but there has been a frost on our spring night! And now the end has come. So listen to my last piece of advice: exegesis, exegesis and yet more exegesis! Keep to the Word, to the scripture that has been given us (259).

Theology and Church

Theology, of course, is what Karl Barth is most well-known for. This was not only the field of his expertise, but also his passion. As early as 1902, shortly before his sixteenth birthday, and on the eve of his confirmation, ‘I made the bold resolve to become a theologian: not with preaching and pastoral care and so on in mind, but in the hope that through such a course of study I might reach a proper understanding of the creed in place of the rather hazy ideas that I had at that time’ (31). Theology, for Barth, is a human endeavour of response to the Word of God spoken to us in Jesus Christ. It is faith seeking understanding, the free and joyful science of God who has given himself to be known by us. It demands our very highest, deepest and most concentrated thought, and yet it is still grace if we come to know God at all. Indeed, as Barth struggled to grasp how he might arrange and structure the doctrine of reconciliation, ‘I dreamed of a plan. It seemed to go in the right direction. The plan now had to stretch from christology to ecclesiology together with the relevant ethics. I woke at 2 a.m. and then put it down on paper hastily the next morning’ (377). Barth’s doctrine of reconciliation (Church Dogmatics IV/1-4) is seen by many as a modern classic—and its outline came in a dream!

But theology, for Barth, is a discipline in and for the church, and indeed, for the entirety of his career Barth remained a man of the church. It is no accident that his major work is called Church Dogmatics—he had changed the title from an earlier attempt which was titled Christian Dogmatics. Barth wanted to make sure that theology is an activity of the church, and that the church rather than the academy was the proper locus for theology, although theology could legitimately be undertaken in the university so long as it remained true to its proper theme and method. Barth did theology to support and inform the proclamation of the church, and throughout his career pastors and preachers remained amongst his most avid readers. If only that remained true today! Theology is not an end in itself, but exists as a ministry of and to the church that it may be faithful in its other ministries of preaching and teaching. In so doing the church remains a teaching church and a hearing church, the place where God’s gift of revelation continues in the power of the Holy Spirit, and the church is thereby continually formed and reformed, gathered, built up and sent.

Praxis

Not only is theology in and for the church, but as Busch makes crystal clear in his account of Barth’s life, theology is also and simultaneously in and for the world. Theology is done in the world as well as in the church, for God’s Word comes to us as people in the world and God’s call makes us responsible to the world. For Barth, then, theology and ethics belong indissolubly together, and always in this order: right thought about God issues in right thought about the world and the church’s life in the world, and so generates an active life in correspondence to the active God revealed in Jesus Christ. Barth lived an active life in the world. During his Safenwil pastorate (1911-1921) he was known as the ‘Red Pastor’ because of his socialist convictions and activity on behalf of the poor workers in his village undergoing industrial transformation. He was deeply involved in the Confessing Church and the theological and ecclesial resistance to Hitler. After the war he pleaded for the forgiveness of the Germans and participated actively in its reconstruction, and was just as deeply involved in the politics of the Cold War, at odds with his many friends on both sides of the Atlantic because he refused to be caught up in anti-Communist fervour, but instead sought to support the church living under Marxist regimes.