Mark’s Passion Narrative (1)

This is surely one of the most poignant stories in Mark’s gospel, even more so given its setting. In this passage we see again something common in Mark’s gospel: one story inserted into another. Mark uses this ‘sandwich’ technique to highlight a common theme between the two stories, or alternatively, a contrast between them. In this instance, the beautiful story of a generous act of devotion (vv.3-9) contrasts with an overarching narrative of vicious conspiracy, hate, and betrayal (vv. 1-2, 10-11).

You can read the passage here.

We are in the final days of Jesus’ life. His religious opponents want to kill him, stealthily, for they are afraid of the people (cf. 11:32). The people considered that John Baptist was a prophet; they seem to have a similar or even higher regard for Jesus, especially as we consider their response to his entry into Jerusalem (11:1-10). The chief priests and scribes are pursuing their own agenda, one not shared by the people. That they were determined to act in secret should have been a warning to them that their intent was not ‘above board.’

Jesus was at the home of Simon (the leper!), reclining at table in the company of others. Mark does not say who these others are, though Matthew states quite plainly that it was the disciples (Matt. 26:8; cf. Luke 7:36ff). Perhaps Mark wanted to avoid this since he has already noted that the disciples have ‘left everything’ to follow Jesus (10:28).

(I prefer not to harmonise the accounts in the four gospels since they seem to have a different context and content, especially in Luke and John. This may reflect variance in the oral tradition or the gospel authors’ editorial purposes. Although an interesting question, it is one to explore some other time!)

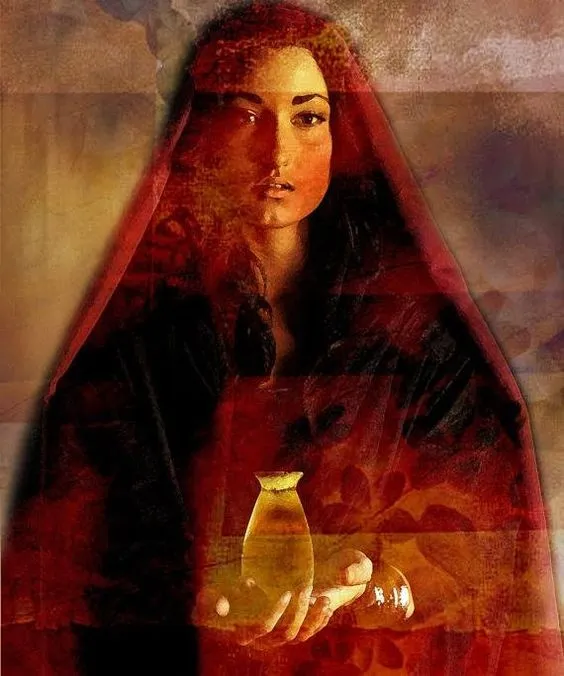

During the meal an unnamed woman approached and poured expensive perfume over his head. We are given no motive for this act in Mark, no context. What has she done and why has she done it? What led to this? What was she seeking to express or communicate? What was she saying—for herself? What was she saying—to Jesus? Why here, why now? How did she have access to so great a treasure? Was it a spur of the moment act, or something well-considered? Will she, did she, later regret it? How would she explain it?

We don’t know. The woman never says a word. Others around the table, however, have plenty to say. They are indignant and critical:

“Why has this perfume been wasted? For this perfume might have been sold for over three hundred denarii, and the money given to the poor.” And they were scolding her (vv. 4-5).

We now see the extent of the woman’s act: 300 denarii was a year’s salary for the common labourer. This is an extraordinary, an outrageous, act; such a fortune, simply poured out! How much good this money might have done! How noble it would have been to give the money to the poor! How practical, how necessary! What a waste simply to pour it out!

And how virtuous the critics appear, quite prepared to do something with someone else’s money! It is too easy to sit in the critic’s chair, comfortable and uncommitted, non-participatory and non-productive. It is too easy to sit in the critic’s chair and to launch barbs at those who are active, who are committed, who are doing something. Such indignation and criticism provide a false sense that one is ‘doing’ something. It betrays a sense of superiority, of finer judgement, of better knowledge.

The critics perhaps feel secure, knowing that they are criticising someone socially inferior, a nameless woman, a ‘nobody.’ But Jesus defends the woman saying,

Let her alone. … For you always have the poor with you, and whenever you wish you can do good to them; but you do not always have me (vv. 6-7).

Is this a veiled rebuke from Jesus to the critics: “If this is so important to you, don’t just talk about it, nor criticise this woman: go do it!” Whenever you wish you can do good for the poor!

The story of the woman’s act stands in contrast to that of Judas, the chief priests and scribes, and the ‘others.’ Judas values Jesus as having some worth: he could be betrayed for some money. The chief priests and scribes ascribe ‘negative value’ to Jesus: he is a worthless person, a threat to be eliminated. The ‘others’ consider the woman’s act a ‘waste’ though Jesus says that she has done him a good deed (v. 6). She has, in a public act that appears to spring from gratitude and devotion, given him an outrageous gift, perhaps all she possessed (cf. 12:44)—and he has with gratitude received it and honoured her.

Nothing given to and for Jesus is ever wasted.